(UPDATE - August 2007)

The tale of a very old, young man and his very young, old car

I'm not certain why I'm putting this section up, but it seems important, if nothing else because the little car in question has been a part of my life, in one way or the other for exactly fifty years. I started it when 15 years old, got it running a few years later, then it sat in my old shop in Nebraska for nearly 40 years before I retrieved it and brought it out here to Arizona last year where I'm now bringing it back to its former non-glory. Not for one second of the intervening four decades was the car more than a millimeter from my heart.

|

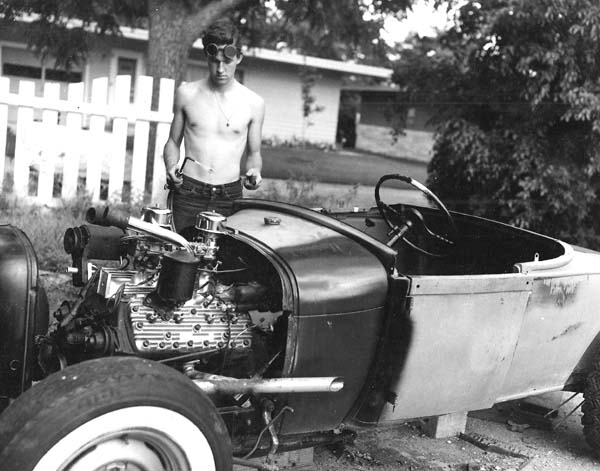

Circa 1958, was I ever

that skinny? Note the bedstead headers |

Maybe the reason I feel compelled to tell you the on-going story of this 1929 Model A roadster is just to show that there is such a thing as continuity in the universe. We're both, the car and I, survivors. We were together at the very beginning and it looks as if we're coming back together again at the end. We started life's journey together. I guess we'll end it together. May the circle, be unbroken, may the...you know the rest.

I started writing this thing with no particular goal in mind. So come back and visit from time to time because I think this may mutate into an on-going philosophical discussion about life, liberty and the pursuit of things that go fast and make lots of noise. Sort of a Zen and the Art of the Street Roadster. Being a person who can't think in a straight line, however, there are likely to be lots of tangents about those things of importance to folks who love the art and the philosophy of the machine, regardless of what that machine may be.

I'm not kidding you one bit when I say that this car IS 1950's small town America. Through it I can smell the French fries, feel the saw dust on the gym floor under my stocking feet, hear the sound of dual pipes wrapping up between the cornfields and remember so clearly what America was like when everything was black and white. It was cars and rock and roll and the hope you might get to first base before you graduated. Few of us seriously thought we'd actually get laid. We were all virgins in more ways than one. Then the 1960's rolled around and took care of that in a hurry.

Those of us of the class of '60 are sort of schizophrenic because we were raised in the relative purity of the '50's, but then we were tasked with the mission of creating the furor that became the '60's. When I left high school I didn't know a single person who had even seen grass. When I left college and cleaned out my apartment, I found a half a brick of hash my roommate had mis-placed. The changes were literally mind-bending, but through it all, the little roadster survived. And so did I.

My plan is to add some photos and a paragraph to this story now and then to let y'all know how the project is progressing. In the mean time, I'm going to post some pictures of the car as we dug it out and tell its story, in case anyone gives a damn.

|

Picture could be taken

only after the'29 Model A mail truck and '29 tudor I had

crammed into the same space with the roadster were moved.

Also had to remove a layer of cream cans that covered the

entire car to make it visible. This is what buried treasure

actually looks like! |

The Roadster's History

In a nut shell, when I was 15 years old I decided I wanted a hotrod like those you saw in the pages of the California hotrod magazines like Rod and Custom.

To me, California Hotrod meant only one thing: an open wheeled roadster with no hood and a chromed engine. I can even tell you exactly where that desire came from: we had taken the train from my hometown in rural Nebraska to see my aunt in North Hollywood. The year was about 1951 and I was nine years old. We pulled into the parking lot of the famous Brown Derby and, as we did, two black highboy street roadsters pulled in next to us. I can still feel the hair standing up on the back of my neck as I plastered my nose against the widow of our car. I was seriously hooked.

Even though I didn't have a drivers license, I started looking for the illusive roadster body to make my hotrod out of. After a lot of back road cruising with friends, I finally found a '29 Model A roadster body being used to stop erosion in a gully. Remember, this is 1957 and we're about 30 miles west of Lincoln, Nebraska. The average, perfectly drivable Model A Ford sold for $25 and the roadster was free for the taking.

The bits and pieces for the front end and driveline came from Marv Tobin's junkyard, which might as well have been Disneyland to me, I found it so fascinating. I remember discovering and buying a V8-60 front axle, one of the round ones, for $1.50, wiring it to the handle bars of my bicycle and pedaling home with it. I was so proud I couldn't stand myself.

|

| Look carefully at the frame you'll see one of the crudest "Z" jobs ever done! Also, the bedstead headers haven't even rusted. And take a look at the headlight stands. The most amazing part was that even though I parked it with the radiator still full, the engine was free and started turning, when we pulled it out of the Quonset. |

My father had forbid me to buy a "hotrod engine" meaning a Ford V-8, which was a potential problem. But not a big one. In those days, when you were 15 years old, you could get a drivers license to drive to school if you lived outside of the district. Friends of mine had been driving a '39 Ford two door, which their father retired in favor of a later Chevy. I followed them down to Tobin's and lifted the engine out of the '39 while it was still warm. But, then I had to get it home and couldn't use dad's truck to do it. So, a friend and I put the engine in a little wagon and pulled it over two miles home up and down hills. It was nearly a year before dad found out I had the engine.

If you'll read the words at the end of this, you'll get an inkling of where the speed parts for the engine came from.

The bottom line is that the little car is now sitting in my shop and I'm hammering away on it knocking some of the crudeness off of it, but not deviating one iota from what the car was when I last drove it in 1962. I'm not going to replace anything that was on it with something newer and I'm not using a single reproduction piece.

|

| My hotrodding buddy from highschool, Dean Hillhouse, mans the floor jack to keep the front tires off the ground. We did this because as I was towing it with the tractor, everything suddenly jerked to a stop and I thought some gears had broken. Dean said not to worry: all of the flats on the petrified tires had hit the ground at one time. My sister, Trish, looks on and sadly nods: yes, her older brother never did grow up. |

I found, among other things when I started the rebuildling process, that I was an unbelievably crude craftsman when a teenager. For one thing, it looked as if I didn't own a drill because every hole was cut with a torch. The major stuff I had welded by the Vogel Brothers, but everything else I did and it looked like I'd squeezed a sparrow and made him crap along the joint, the welds were so bad.

Flash ahead 42 years: now that kid is the 52 year old proprietor of a one-man bodyshop that specializes in hotrods and antiques. I called Lowell Krueger, the day I exhumed the car in 2001 and said, "Hey, Lowell, how' d you like to do the body work on my old roadster."

He answered, "I've been laying awake nights thinking about that car for 40 years, knowing it was sitting in your old shed. Bring it on up."

Later, my good friend, Dean Hillhouse, who hotrodded with me in high school, brought the car down to me in Arizona. He runs a radiator shop in Lincoln, Nebraska just like his dad did. One day his shop manager looked at my old radiator and said, "Did you build this radiator" and he said he didn't. His manager said, "Look at the patches. They are done exactly the same way you do them." Dean's dad had built the radiator for me!

Because of the history in the car, I've decide that as much as possible, no one is going to work on it who didn't work on it first time around and as few parts as possible will go on it that weren't on it when wheeled into the garage for the last time 40 years ago. This includes stuff like the BT-13 Vultee airplane bucket seats and the over-the-frame headers made out of old bedsteads.

Folks, 'you want to see a 1950's hot rod? Well this is it!

I'm hoping I have enough energy to keep updating these pages, but don't get too aggravated, if I'm slow doing it.

|

That's me on our family's '53 Farmall Cub that we bought new and are still using it today. It pulled the old road toad out in fine style. This is the first time it had seen daylight in nearly 40 years. The mangled tires actually held air, when we put a hose to them, and the rear ones were tubeless!! They stayed on the car until last year, when I put a set of bias ply Cokers on them. |

|

Here's how it looks today, August, 2007. All the systems are in and ready to go. See the progress reports to share in the drama of trying to relive your high school hotrod dreams knowing what you didn't know then. |

Progress reports UPDATE - August 2007 |

The following are some words I wrote on the plane when going up to dig the old car out.

Tale

of Two Survivors: The Roadster and Me

by

Budd Davisson

The cornfields along Highway 34 a few miles west of Lincoln, Nebraska sped past the Greyhound's windows. A familiar green monotony, they held no interest to me, as my mind was somewhere else. Maybe I was streaking across El Mirage, pedal to the metal, a rooster tail of dust behind marking my roadster's way to a new record. Or maybe cruisin' Van Nuys Boulevard, where even guys like Von Dutch would notice my '29 low boy.

As the bus made it's way back to my small hometown, the images filled my 16 year old mind and I fiddled nonstop with the various things that twisted and turned on the Offenhauser two-hole manifold sitting across my legs. After the first few miles, the other passengers stopped giving me odd looks. I became just a skinny kid with a ducktail who clung to the car part in his lap as if it were his Velveteen bunny. I ignored them as I fondled, fiddled and manipulated my prize. The carburetors, the fabled 97's, weren't matched. One was chromed one wasn't. But the air cleaners with the surrounding screen festooned with punched out holes which said "V-8" were almost like those I'd seen in the magazines, and the locations in the magazines, the places with all the cool cars, was where part of me lived. That was the part that wanted desperately to have a car like those guys had. A true California hotrod roadster.

Only an hour earlier I'd been over at Speedway Motors, a modest store front on Lincoln's "N" street and a tall, easy-talking guy who introduced himself as Bill Smith, had accepted my hard earned $25 dollars for the intake set up. He'd tossed in the polished fuel block for nothing.

Bill Smith had seen me often, as I'd take the bus from my home town of 2,700 hard working souls to the big city for the express purpose of looking at all the magical stuff hanging on the walls behind his counter and spread out around the rather shallow retail area with the storage behind. God, I can still smell the place in my mind! He even had one of those new Chevy V-8s dressed out in chrome and on a stand where we could all drool over it. The pilgrimages to his relatively tiny business wouldn't find me leaving with something tangible very often, but this time, I'd hit the jackpot. I had a dual carburetor intake. Now I was a real hot rodder!

Looking back at that time from the other end of history's telescope, I can see myself now as others must have seen me: a typical small town kid trying to be like those he saw in Rod and Custom or Dig magazine, sitting in a bus in rural Nebraska with a used, but very much loved, dual carb set up in my lap.

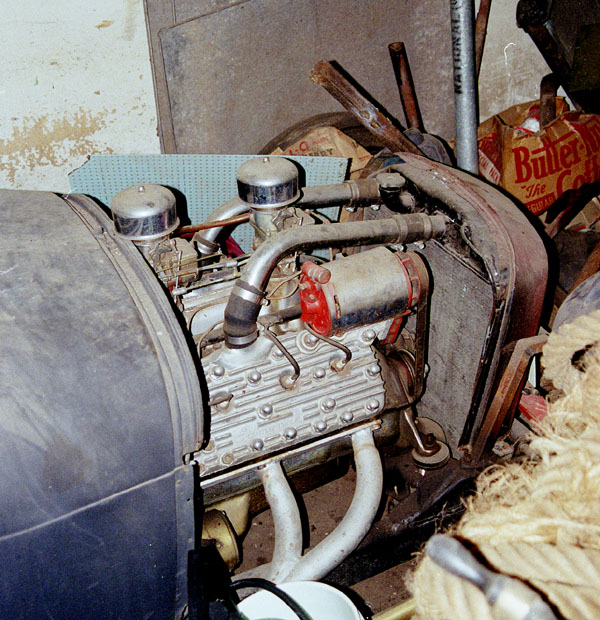

Now, flash ahead 42 years, and it's July 4th weekend on the first year of the new millennium. I had carefully picked my way through the junk towards the back of the small Quonset hut that used to be part of my father's hatchery (on a hot day you can still smell the chickens). Even throwing the side door open couldn't break the vague darkness that had settled on the place where I had spent some of my happiest years building things that ran (sort of, anyway). The narrow shaft of light lay like a bright splash from a paint brush that revealed dust laden, dark primered metal, and familiar curves. Even through the cob webs and dust, the not-quite-dead shine of a pair of bonnet air cleaners broke through the gloom. Then came the ribbed reflection that I knew came from another Speedway acquisition, a set of Edmunds hi-comp heads.

My wife, the Arizona Redhead, asked from behind, "What can you see."

For a second, Howard Carter, the gentleman who discovered Tutankhamun's tomb, flashed across my mind. When peering through a hole into the tomb, he was asked the exact same question and I answered the Redhead with his words. What did I see? I answered, "Things. Wonderful things!"

I had come full circle to the place where it had all started. The roadster sat there, layered with miscellaneous junk and the tires becoming one with the pavement. The windshield was still broken where Jay Cattle had hit it when launched from his seat while the roadster vaulted over a curb. Craig Colburn, wanting to see how fast he could make it around the little traffic circle in the Hughes Addition, had pulled the steering wheel off in his lap and wound up in Bud Yerk's front yard. I'd forgotten to tell him I'd never put the nut back on the old Ross steering column.

The over-the-frame headers, made from cut up bedsteads, hadn't rusted through the silver paint, which surprised me. The bucket seats, from a dead Vultee BT-13 WWII trainer, were still there, the cushions being nothing more than the bottoms from seats stripped out of the Rivoli movie theater, when it was rebuilt. The '40 dash still stared back through blind eyes, because I never did get around to cutting the holes and installing a speedometer. Or any other gauge, for that matter. They weren't needed. You knew when you were going too fast, when you got scared. You knew when the generator wasn't working when the lights went out. You knew when the '39 V8 Ford was hot (which was always...there was no fan), because vapor would start blowing past your squinting eyes. You knew when you were out of gas because you were coasting silently towards the curb.

I crawled over the top of the unbelievably dirty car to see it from the front. I couldn't walk about it because my '29 mail truck was squeezing it against the wall. In fact, there was so much car-related junk scattered around it, it was impossible to find a space on the floor to stand. I had to pick my way from this teetering '40 Ford rim to that rusty can of paint and so forth, like crossing a rock strewn shallow stream.

Around up front, I found the shortened '34 truck shell covering the '40 radiator. I glanced around, searching. Yes, there it was, hanging on the wall where I had left it 40 years earlier. There was the $10 deuce grill shell, my cousin had secretly sold me at Speedy Bill's place. "Hey, Budd, I'm giving you a REALLY good deal on this...ssshhhh!"

More to come.