|

The "Other" Piper

Cub |

PAGE TWO

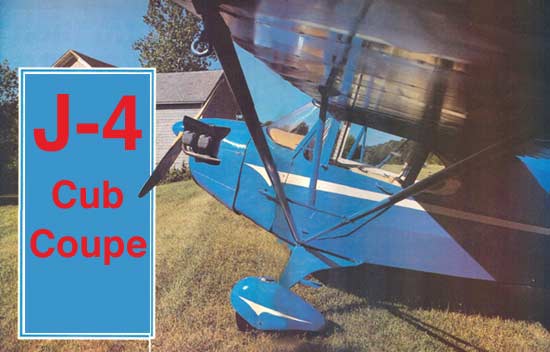

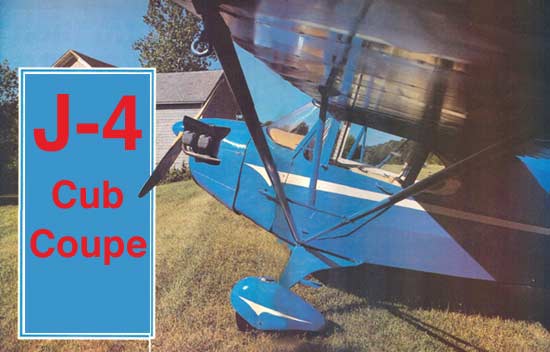

Bob Hunt is like most people with small fun-flying: machines: Enthusiastic and always willing to fly. It was the same enthusiasm that got him into aviation in the first place and led him to buy his 1939 Cub Coupe when he had only eighteen hours in his log book. "I started in the Cessna 150 but, after I bought the Coupe, I did most of my local solo flying in that and by the time I took my private check ride in the 150 I had almost as much time in the Coupe." In watching Bob bring his Coupe down final, there was no mistaking its Cub heritage. Even as I walked around the bird on the ramp it was possible to say “…that's from a J-3 and so is that.”. The wings and tail are identical, although the rudder does have a little more area in the bottom corner. The fuselage and landing gear, however, are definitely not J-3 Cub. You don't add a foot to the width of a fuselage, put a door in both sides and make believe it's the same unit. It would have been very easy for Piper to screw up the fine lines of the Cub by making it fat and dumpy. Somehow the lines flow smoothly from the rudder post to the spinner and look as if they were always that way. The sharper observers of Cub characteristics are going to look at the gear and ask "What the hell happened to the bungees?" Breaking with tried and true Piper tradition, before and since, the J-4 sports a spring loaded "V" gear similar to a Champ which gives the plane a much cleaner appearance. UNDOUBTEDLY THE LARGEST SURPRISE THE J-4 COUPE HOLDS is the cabin. It's easy to get into and you and your passengers don't have to assume an embryonic position to fit into the space available. Almost without exception, all of the two-place side-by-side airplanes of the era required a short course in yoga to enter and exit. In fact, in exiting a few of them it was easier to fall out backwards and hope you didn't break anything important when you hit. Not so with the J-4. The door/strut/step/position is such that boarding is a no sweat proposition. The cabin width and height on the J-4 breaks with its two-place contemporaries. The wing appears to be mounted appreciably higher than something like a Taylorcraft or a Chief, which eliminates the claustrophobic phone booth feel associated with both and greatly increases the visibility to the point that you are merely "blind" to the sides and not "stone blind." This difference should not be underestimated. It makes the airplane very enjoyable. ON TAXIING OUT, IT DOESN'T TAKE MUCH TO remind you that the era represented by the J-4 is 1939 and not 1979. The tail down position tries to put the nose up in front of you, but a little stretching or a thin cushion puts you up high enough to almost see over the nose. The rudder is quite effective in pointing you in a general direction while taxiing but, if you want to get more specific about it on tightening up a turn you have to swivel your heels inwards to pick up the heel brakes that huddle together between the rudder pedals. As is my habit, I flew the airplane from the right seat, which had no brakes, so periodically Bob would have to respond to my request for "A little right brake, now a little left."

I am almost embarrassed to talk about my first takeoff in the J-4. It had been so long since I had flown a putt-putt of this sort that—without thinking—I used Pitts' technique on takeoff, i.e., keeping the stick full back until I had plenty of power on it and it was rolling. On airplanes of this type it is standard procedure to hoist the tail immediately upon application of power, which gives you plenty of rudder and much better visibility. The Coupe's response to me acting like a dunce was to waddle off the ground in a three-point position and then settle back down to kiss the runway, when I relaxed the back pressure. In later takeoffs, I did what I should have done in the first place; got the tail up to let the Coupe run on its mains until it was ready to fly. In that position, I found the rudder asked for a gentle touch because that long moment arm gave the rudder plenty of authority. Just the tiniest bit of pressure is all that's needed to make the plane head one direction or the other. With two people on board and the outside air temperature working its way towards 90 degrees, that little 65 horse Continental wasn't about to give us blinding acceleration on climb. What it did give us was a rather relaxed climb of maybe 400 feet a minute at an air speed of 60 to 65 mph. The attitude in climb is surprisingly shallow and just a little bit of neck stretching lets you see around the nose to keep from bumping into someone who doesn't enjoy the same visibility. In the air, the controls are as one would expect—very Cub-like although the stick and rudder placement is much more natural. To my taste, the Cub's stick has always been too tall and little too close to me, but this is not the case with the J-4. YOU DON'T SPEND MONEY ON AN AIRPLANE LIKE a J-4 Coupe expecting to use it for shuttling between Boston and Chicago. You buy it for cruising along on a warm summer's evening, watching the sun repaint the landscape, while the cares of the day disappear in the slipstream. The J-4 will very happily show you 75 to 80 miles an hour at cruise while sipping down 4 to 41/2 gallons of fuel an hour. Traveling in a J-4, whether locally or to a hundred mile distant destination, is reward in itself. The trip is the goal, not arrival at the destination. The trip is the art of being airborne in a machine that loves it as much as you do, and coming to rest at your destination finishes that part of the aerial painting. The Cub Coupe doesn’t fly to take you places, it flys so that it can share the third dimension with you. This is neither a Bonanza nor a Centurian. It is not even a Cherokee. The Piper J-4 is simply itself and allows those with limited resources and a taste for things aeronautically unique to go out and play with the swallows and hawks. Landing in the J-4 is not so much a landing as it is a maneuvering of the airplane close to the ground, where the J-4, and not the pilot, decides it's time to land. All the pilot need do is work his way down to the runway and very gently conform the attitude of the airplane to the ground. Of course, it's helpful if you keep your final approach speed down to 60 mph or so. With those long wings, any extra speed translates into more float than you know what to do with. But, in any case, if you come down to the ground and the airplane doesn't want to land, it's too fast and, if you just wait long enough, it'll slow to a halt and gently deposit you in the grass. On the day we were flying we had a helpful 10 knot wind right on the nose and the airplane would seemingly slow to a halt, while still suspended above the grass and then slowly let you touch down. While doing stalls at altitude, I found that the needle is down below 40 mph before the wings begrudgingly gave up their hold on life and let the nose slouch forward in a noticeable, but soft break. The handbook says 38 mph for the stall and with 10 or 12 knots on the nose our landing seemed to prove out the fact that the J-4 Cub Coupe was capable of landing with almost the same ease, speed, and safety of an Ultralight. The J-4 Cub Coupe is obscure . . . it's unknown. You might even say

that it's unpopular, which is to say nothing bad about the airplane.

Not enough were built to achieve popularity by numbers, such as the

J-3 Cub did. Because of that, the J-4 Coupe represents one of the all

around best bargains in a little two-place airplane that gives you

not only the ability to taste a golden sunset, but also places you

in a time machine that lets you peak over the last horizon and into

yesterday. Its birthdate says antique. Its lines say classic, but its

mechanics and usability are as up-to-date as the fun of flying. BD |