|

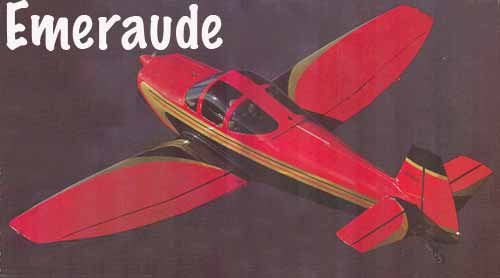

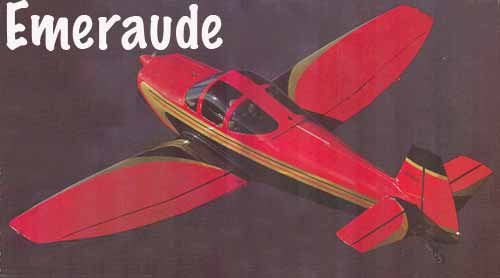

The Wooden Emerald |

PAGE TWO

With his background both as a machinist and a cabinet maker, the Emeraude would be a natural since it definitely needed his magical touch from nose to rudder. He had to machine the landing gear and manufacture it from scratch, as well as apply wing skins and build a fiberglass cowling. He is particularly proud of the sliding canopy which incorporates a little of each of his skills from metalworking to fiberglass to plexiglass forming. "The biggest headache in building the whole airplane was Moser himself,” laughs Crichton. "Every time I turned around he wanted to add this or that. You would have thought we were building a Cadillac." The final product was a typical St. Augustine homebuilt, in that the plane was about as well-detailed as homebuilts normally get and incorporated a little of everyone's thoughts. The colors borrowed heavily on those which had been applied at St. Augustine on the Wedell-Williams replica. Moser took the basic red, black, and gold combination and came up with a drawing that Ricky Evans, of St. Augustine Aircraft Refinishing, could change into three dimensions. Just about everyone on the airport has flown the airplane so, by the time I climbed up on the wing, it had in excess of 60 hours in just the last few months. The airplane had been so trouble-free and straightforward that the pilots had fallen into using it as a parts chaser for all the projects underway. When I started to settle down into the cock-pit, Big Al ambled up with an armload of cushions and said, "I think you'll probably need these" I said "Let's see," and then I sat down and proceeded to disappear! I had forgotten this airplane had been built around the dimensions of two guys, which were 1.3 times the size of the average FAA pilot. In fact, when they made their first flight together, there were 13 feet and over 500 pounds of pilots on board. I wound up with two cushions behind me and one under, just to be able to reach the rudder pedals and see over the nose. The airplane sits so low to the ground, getting up on the wing and stepping into the cockpit is something that could even be accomplished gracefully while wearing a dress (although I didn't try it). I saddled up on the right side — since that's the way God meant us to fly — with the stick in my right hand and reached overhead to slide the canopy forward. Although I knew the canopy must weigh plenty, it slid smoothly for-ward to be captured by the single overhead latch, and I glanced back at the corners of the canopy to see both pins had engaged exactly the way Big Al had designed them. In glancing around the cockpit I had to smile — homebuilts sure ain't what they used to be! It hasn't been that long since a homebuilt airplane would look like it was homebuilt — with lots of ragged corners and contact cement showing around the edges of the cheap vinyl upholstery (assuming there was any upholstery at all). All the metal would be painted flat black and smudged with fingerprints, and the instrument panel would have an uneven coat of crackle-finish paint, which would already be flaking. Looking around the Emeraude, I was reminded of how far homebuilding has come. Ten years ago, Big Al's instrument panel layout would have been highly unusual because it was so professionally done and perfectly designed. Today, we are seeing more of this type of thought and craftsmanship. Big Al's artistry in the Emeraude has produced what has to be one of the very best homebuilt panels and interiors done to date. I hollered "clear" and twisted the key, asking the 0-320 150 horse Lycoming to come to life, which it did on the very first blade. Oddly enough, after it started and settled into idle, the engine seemed vaguely distant and isolated, as though it was mounted on the far end of a bale of cotton. This was a feeling and a characteristic I was soon to associate with every aspect of the machine. This is one airplane you really can't claim to be taxiing, even though you are moving down taxiways en route to the runway. The tailwheel is so smoothly and perfectly matched to the rudder input that you have to replace the term "taxiing" with the term "driving:' Other than a very slight blind area directly ahead, the only thing that differentiates this airplane from a nosewheel airplane or a Chevy is its butt-on-the-pavement stance. There is no tendency for it to overreact when the rudder pedal goes down, and the slight lag often associated with spring-controlled tailwheels was gone, as well. The Emeraude just naturally goes the direction of the foot that's down and does so with exactly the amount of expediency exhibited by said foot. Nudge the rudder and it gently nudges the nose side-ways. Boot the rudder and expect to be booted back. With all of that right-mag, left-mag stuff out of the way, I rolled out onto the centerline and glanced out at the leading edge of the flaps, as I toggled the electric flap switch down. When I saw the number 15 show up in the gap between the flap and the wing, I knew I had 15 degrees and let go of the switch. As all those Avco ponies started to wake up in response to my prodding with the throttle, the airplane started accelerating at a pace not unlike a lightly loaded Bonanza or C-210. It wasn't about to leave any pilot breathless, but he wouldn't be bored either. As soon as the throttle stopped moving, I very gently edged the tail into the air, which instantaneously gave me a bay window view of the pavement being sucked under the nose. Even though I was holding a slightly tail-down attitude, no piece of nosewheel sheet iron could have given me any better view — or any better control. Even though we had a slight left crosswind, the airplane showed no urge to do anything other than truck straight ahead. In fact, I was barely conscious of using my feet at all. The tail's low stance let the airplane fly off at about 65 mph, although I wasn't paying a heck of a lot of attention to the numbers, since I was more interested in keeping the nose in front of me and holding a stable attitude. In no big rush to go anywhere, I just let the airplane accelerate to a speed where it seemed happy and let it sit there going upstairs. Once I glanced over, the number happened to be 95 mph, and we were showing about 850 to 900 feet per minute vertically. Bringing the throttle off the stop just enough to relax the tachometer

needle a little, I let myself pay a little more attention to what

I was hearing and feeling — which wasn't much. I was very conscious

of the airplane being unreasonably smooth and quiet. It wasn't until

that moment that I realized most airplanes have a background current

of subtle vibrations. They always let you know you are sitting in a

machine, and somewhere in that machine is a four-cylinder thumper pounding

away and making every little panel and piece of structure resonate

to its own melody. But try as it could, that bullet-proof 0-320 up

front, which is known for both reliability and ability to shake

airframes to pieces, couldn't get at me with either noise or vibration.

A wood structure naturally dampens all vibrations, both mechanically

induced and those being fed into it by the air it's punching a hole

through. The structure soaks up so much of what is being fed into it,

the pilot feels as if he is sitting in one of those hyper-expensive,

liquid-damped driving seats we see advertised as being an item that

is ab- Leaving the pattern, I started playing with the climb speed trying to figure out what number seemed to fit best. Beginning at 95 mph and just a shade short of full blower, I began bringing the nose up in five mph increments, cross-checking the VSI and the panel-mounted clock at the sametime. By the time the rate of climb peaked. we were down around 85 mph and showing nearly 1100 feet per minute climb. It was probably a little better than that, since I had worked my way up to 3000 feet and hadn't compensated for the altitude. Leveling out, I brought the power back to what seemed like a super-conservative setting of 2300 rpm and watched as the air-speed stabilized at 105 knots — a speed verified as being about three knots low, when one of my buddies fell into the right wing position in an Extra 300 to pace me. Bringing the power up to a more reasonable cruise configuration of 2550 rpm, the speed climbed slowly to 120 knots. And I do mean climbed slowly! Every so often I would think it was going as fast as possible and then I'd look down to see it had picked up another knot or two. The totally "dead" feeling of the airframe makes a pilot a little more aware of what the airplane is doing aerodynamically than he would be in a similar situation in a more conventional metal airplane. If the Emeraude buzzed and vibrated like most airplanes, undoubtedly most pilots would miss some of the airplane's nuances, but the absence of distractions makes it easier to concentrate on them. In playing with the various axes, it was found, the airplane is barely positive in roll stability, which puts it right up there with probably 90 percent of the factory-built airplanes, but it is a little bit better in pitch. Yaw stability is okay, but in punching that the rudders it becomes immediately apparent the rudder pedal may be moving, but the effect is minimal at best. The airplane is very definitely short on rudder authority. Fortunately, as would be expected, this is no big deal since the airplane has practically no adverse yaw, in normal flight so only the tiniest amount of rudder is needed. With that long arm and generous side area, there is a good possibility in a hard crosswind that the rudder may turn out to be the limiting factor. This might especially be true in a left crosswind on takeoff where torque and P-factor are adding to the effect of the wind, and the rudder may not be able to handle it adequately. That theory is pure conjecture on my part. since not once in normal flight regimes did I feel as if we needed to hang a barn door back there to keep the airplane under control. |