|

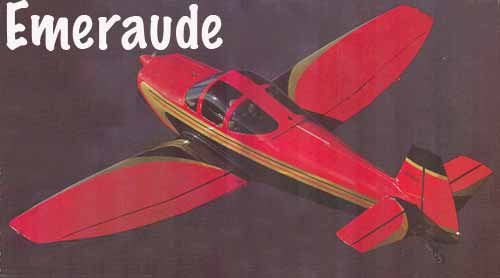

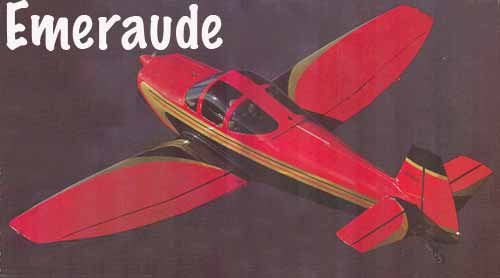

The Wooden Emerald |

PAGE THREE This lack of rudder authority may be one reason some Emeraudes are seen with vortex generators running up and down the vertical stabilizer, and it may also be why on the current plans version, the "Super" Emeraude, the tail is angular and swept — adding both arm and area. There are those who feel the new "modern"-looking F-86 type tail surface is out of keeping with the near feminine curves of the rest of the airframe. With all of the feminine nature of the airplane and its absolutely genteel feel and handling; I was a little surprised to find the stall had a slight macho edge. Maybe this lady did have a surprise or two hidden away. As the speed is bled off down into the mid-50s, the airplane proceeds to unload with absolutely no warning whatsoever. One minute everything is fine, and a nanosecond later the wing has leaped over a fairly sharp peak in the lift curve and turned the airplane into a thoroughly dynamic falling object. Don't read this to think it's an uncontrollable stall, because it's anything but that. The moment back pressure is released, the airplane is happily flying again, but it would be very easy for the semi-dozing pilot to hold the airplane off the runway a little bit too long and suddenly find himself deposited on the runway like a lump of something rather unpleasant and smelly. Running the flaps out lowered the stall speed maybe three or four knots and got the nose down, but once they traveled past about 20 degrees they didn't seem to con tribute much of anything other than drag. Also, as would be expected, they sharpened up the stall just a little bit more, although not as much as I had expected. As I turned and headed back toward the airport, I decided to make it easy on myself and make it a half-flap three-point. Okay, so I could have gone for a wheel landing and not worried about the stall at all, but somehow this airplane seemed to ask to be three-pointed because wheel landings were a little too rough for its gentle nature. Besides, I felt like I would be chickening out. Setting up the approach, I just made believe I was in command of a Cherokee 140 or something similar, since those were the characteristics the airplane appeared to mimic in glide. As I got closer to the ground, it was quite obvious the airplane was not coming down anywhere near as fast as a Cherokee in the same situation. Even though I had half-flap out, I gingerly eased it into a slip to find out if it would do anything stupid. It didn't. The lack of rudder did limit what I could do in that situation. Fortunately, what little slip it could generate combined with the flaps to bring the airplane down exactly where it was supposed to be. As the airplane and I tip-toed into ground effect. I reminded myself of its flat three-point attitude and sharp-edged stall and resolved to do most of my flaring a little lower than usual. As the ground got closer. I very gingerly started the nose up — at the same time ad-ding just a touch of power. Then, as the nose came into what appeared to be a three-point. I gently bled off the power, dropping the left wing slightly to combat a fairly persistent left crosswind. The airplane squeaked on left main and tailwheel first, the right main coming down to join the other two almost immediately. As soon as it was on the ground the airplane again showed its good manners by tracking absolutely dead straight even though I could feel the wind doing its best to weathervane. With the tailwheel nailed to the ground with back stick. a little right rudder was all that was needed to keep it straight, and at no time was any brake needed. The airplane decelerated so quickly and tracked so straight that I had to use power to taxi up to the next intersection to clear the active. The Emeraude was not Claude Piel's last design, but it certainly was one of his very best. Time has a way of eliminating questionable designs, and the fact that Emeraudes are still being built 35 years after introduction says it all. The Emeraude is still a wonderful airplane for someone seeking a classic-appearing and smooth flying two-place airplane that can be used to its fullest as a cross-country machine. At 140 mph with 31 gallons (including ten in an aux tank), the airplane has plenty of range to give long cross-country legs and take full advantage of the comfortable flight deck. An additional factor that absolutely cannot be overlooked is how much the overall smoothness of the airframe and the motor installation contribute to making those long cross-country legs fatigue-free. It's long been recognized that often the fatigue we feel after a four or five hour crosscountry is caused, in part, by the low frequency vibrations with which our body is being constantly pounded. This airplane brings those frequencies to new lows and does its very best to surround the pilot with soft silence. By today's composite cookie cutter standards, the Emeraude is a wildly complicated, slow-building airplane. But then, by today's composite standards, everything traditional is complicated. The builder of an Emeraude has to be one who enjoys crafting each small part of the project for its own sake. He has to enjoy taking a bundle of lumber that, excluding the plywood, could easily fit into a long ten-inch mailing tube and forming those big pieces into many small ones which, when fitted together, can breathe flight into the overall collection. There is something very satisfying and organic about working with wood and using it to build something which puts life back into it in the form of flight. This is something composites will never be able to duplicate. They may be faster, but they are still an obviously man-made chemical derivation from the laboratory, rather than being a natural continuum that starts with a tiny spruce seedling and progresses through a man's hands into the air. To those sensitive to the natural order of things, taking wood and putting it into the air seems to be going full circle in a form of mechanical reincarnation. It could also be argued that

the builder of an Emeraude is a sculptor in a classic sense — taking something natural and creating

art. It can also be said positively that Big Al doesn't look at himself

as a sculptor (and probably no one else does either). The final

result, however, speaks for itself: If it's not art, what is it? BD |