Here I was again. The nose was just beginning to level

out at 1000 feet AGL and I realized I had forgotten to ask what the

cruise rpm was supposed to be. My log book doesn't show a heck of a

lot of Command-Aire time ( read that as zero), and I couldn't shout

loud enough for Carl Pascarell in the front cockpit to give me any

advice. Left to my own devices, I figured I would just reduce power

a little bit and hope I was close.

As I started to bring my throttle hand back, a hand came up out of

the front cockpit. A finger was reaching over the front windscreen

as if to fingerpaint in the specks of oil on the front side of it.

I watched as the finger etched out a cryptic 1-6-0-0 in the oil and

I realized that was to be our intercom system for the flight. I brought

the throttle back a little farther and watched as the large alarm

clock hand on the tachometer unwound to cruise power ("Ahoy

engine room —give me 1600 turns!").

One of the really neat things about aviation is that no matter how

long you've been in it, no matter how much time you've spent rubbing

elbows with esoteric airplanes, you know that there's a long, long

way to go before you even scratch the surface of our aviation heritage.

Every time you kick over an aeronautical rock, you'll find something

under it that surprises you to no end. A Command-Aire is one of those

surprises. It's one of those machines that existed in my aviation knowledge

only as a name. A name with no history and, until a balmy afternoon

in north Florida, had escaped my logbook.

|

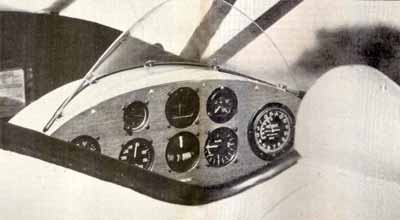

The definition of "basic instrumentation" starts

here! |

The reason so many aircraft flit around the edge of our aviation knowledge

is because a whole herd of companies came and went in a flash in the

era surrounding the crash of 1929. Some historians have

re-ported that as many as a hundred aircraft companies were happily

engaged in stitching fabric, welding tubing, and splicing

wood during the first thirty years of man's endeavors to get off the

ground. Many companies built no more than one or two airplanes before

deciding they were better off refinishing spokes on Model Ts. Others

banged out machines in significant numbers, yet are still virtually

unknown outside the cloistered circles of the hard-core antiquer. The

Command-Aire is one of those. Even as I was being instructed by shaky

lines on an oil covered windshield, I was amazed that the Command-Aire

had fallen into a crack in aviation's memory.

The Command-Aire Company was not one of your storefront or backyard

operations. In the first place, the experts say the company built somewhere

between 250 and 300 airplanes in the period between 1927 and 1930.

But these weren't just any airplanes. The Command-Aire,

for instance, was one of only three aircraft designs to pass the 1929

Guggenheim Safety Trial, in which all existing aircraft designs were

test flown and judged for safety. However, one of the notes reportedly

made by the committee was they thought the 46 mph stall speed of the

Command-Aire was entirely too high for the average pilot.

In truth, I get a little frustrated in talking about the Command-Aire

because I know so little about it and the company. What little

I do know points to a fascinating story of frustration and limited

success .. . leaving behind a very small number of airplanes with which

to judge their designs. Command-Aire's chief designer, Albert Voellmecke,

is probably a story in himself.

GRADUATED FROM THE UNIVERSITY OF BRAUN-schweigaud in 1933, Voellmecke

was hired on by the famed German aircraft firm of Heinkel who eventually

sent him to America in 1927. It says some-thing about Voellmecke that

he had the guts to leave traditional Germany and travel to the craziness

that the United States represented in those days. It says even more

about him that he was willing to leave an established company like

Heinkel to work for a new company like Command-Aire, so he must have

indeed been a pioneer spirit. Today, after more than thirty years in

the CAA/FAA. Voellmecke is still very much alive and very active.

The Little Rock, Arkansas, company of Command-Aire had many firsts.

Besides being one of the few winners of the Guggenheim Trials, they

designed and built something like half a dozen different models.

They were issued fourteen approved type certificates for designs

and. of the total produced, something like 160 used OX-5s while versions

of the 3C3-AT, with the little 110 horse Warner. and the 5C3 with

the 160 horse Challenger are the only survivors.

Two Command-Aires are known to be airworthy, with approximately eleven

known to exist. In addition, a version of the 5C3 was built strictly

as a duster with no provisions for carrying passengers, and is generally

considered to be the first aircraft specifically designed for that

use. Of the seven or eight 5C3s still in existence, all

but one of them were originally dusters.

Command-Aire built one additional airplane that is certainly worth

remembering and that is the little Rocket Racer. The Rocket was built

to compete in the 1930 All American Derby. Equipped with a super-charged

90 horse Cirrus and Lee Gelbach at the controls (later to

gain fame in the hollowed-out 'belly of a Gee Bee), the little Rocket

showed the more powerful contestants the way it should be done. Running

a race course that spanned most of Mid-America, the little Rocket repeatedly

recorded ground speeds of 215 mph, its average point-to-point time

being in the neighborhood of 160 mph. The Rocket no longer

exists, but Joe Armaldi in Florida (our source for much of this information,

by the way) is well along in building a replica of the racer.

With only two airworthy, you don't stumble across a Command-Aire every

time you walk out to the local airport. In fact, my introduction to

the 3C3-AT at St. Augustine was a result of ,Jim Moser's continual

babbling into the phone about how much fun they were having

with this barn-sized antique. This was from a guy who has his choice

of dozens of sporty airplanes to fly, but every single conversation

for a couple of months was punctuated with his ramblings about the

Command-Aire. I finally decided the only way to shorten our phone conversations

was for me to trundle ,on down to St. Augustine and see what the hell

he was talking about.

To someone who spends most of his time in a two-place Pitts, a Command-Aire

3C3 is bigger than your average biplane. In fact, it's bigger than

your average everything. Jim was dragging me around the airplane in

a circle, pointing out better features, but every other sentence came

out "Neat, isn't it?" Since the airplane was actually owned

by a pilot who lives in England and keeps it at AeroSport, in St. Augustine,

for relaxation when he comes to the colonies, we thought

it best to have somebody on board who had some idea of what he was

doing, since I certainly didn't. So Jim threw Carl Pascarell into the

front seat, pointed at the back and said, "go flying."

GO TO NEXT PAGE

|