PAGE TWO

|

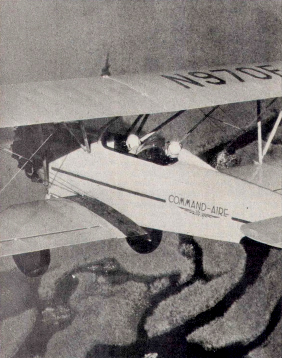

110 hp Warner has exposed

rocker arms. Between them spitting grease and the individual

stacks, there's no doubt you're flying behind an anachronism |

I scrambled up on the lower wing and immediately noticed the sheet

metal had a bathtub-type cutout (i.e., both bathtubs were in the same

cutout, separated by only the rear instrument panel) As I slid down

into the cockpit, I could see one reason Moser liked this air-plane

. . . he's 6 ft 5 in and this is a machine that doesn't even begin

to intrude on his many corners. I, on the other hand, felt a little

lost. Deciding to explore the general territory within the boundaries

of the tubing; I slid my feet up to the rudder bar and it

was just that . . . a bar pivoted in the middle with brakes being of

the heel variety. Historically, I hate heel brakes because you can

never get them when you have the rudder full down and desperately need

them. On the Command-Aire, however, the geometry is surprisingly

good and I found I could always swing a heel inboard and tap a little

brake whenever I needed it.

Aside from the stick, rudders and throttle, there wasn't a heck of

a lot else to look at. I scanned the instrument panel and found it

was somebody's idea of a joke, if only because the airspeed indicator

went up to 700 mph! I knew full well if you threw the heaviest part

of the airplane, the 110 horse Warner, overboard at 10,000 feet, it

wouldn't reach 700 mph before it hit the ground. And trying to force

the Command-Aire past even 200 mph would be like trying to break Mach

1 with a parachute.

In the middle of my musings, somebody yelled "hot and brakes" and

I suddenly found myself sitting behind a seven-cylinder collection

of exposed rocker arms that looked like a bunch of beetles doing a

jitterbug on a radiator. Each one was spitting minute amounts of rocker

arm grease back at those of us fortunate enough to be scrunched down

in the slipstream.

Pocketa-pocketa-pocketa. I brought the throttle up and started wending

my way out towards the runway, occasionally finding it helpful to

stab a little brake to tighten a corner, since the tail wheel didn't

seem to want to give me anything remotely resembling a tight turn.

Lined up into the wind (I had already heard tales from other sources

of the airplane's lack of crosswind capabilities), I straightened out

my left arm and heard the pocketas get closer together until they merged

into a sound that can only be made by a radial engine doing its very

best to pull the fabric-covered hangar behind it into the air.

AS SOON AS IT WAS ROLLING, I PICKED THE TAIL up and found myself blessed

with more rudder than I knew what to do with, which made running down

the centerline no ° problem. Having had the briefest of checkouts

("Budd, you sit there and have a good time."), I didn't know

and didn't particularly care what speed was needed to fly. I just kept

the tail slightly down and the airplane lifted off in what appeared

to be a dead level attitude. I glanced at the airspeed to get some

sort of guide for establishing a climb attitude and, just as quickly,

dismissed the instrument as being there only to occupy the

hole. Yes, the needle came up off the peg, but with the number 700

at the top, you don't get a heck of a lot of movement at the bottom.

I cautiously established something that looked like a positive deck

angle and watched as the altimeter leisurely wound its way up to 1000

feet, where I got my first message in the windshield oil.

I had a little trouble reading my inter-cockpit memos in the oil because

the slipstream was beating the living hell out of my head. I thought

I was sitting too high, but even scrunching down didn't help much.

My guess is the down wash from the wing combines with the slipstream

and curves into the rear pit.

The controls were pretty much what I expected, a bit on the heavy side

with something less than instant response. The date of this

machine's birth didn't demand lightning fast roll rates. Incidentally,

the Guggenheim shouldn't have made a big deal about the airplane's

stalls. Although I couldn't verify the 46 mph figures, since the bottom

number on the airspeed indicator was something like 60 mph, I did find

that a fair amount of yanking was needed to get any kind of break.

As with most biplanes of the period, the Command-Aire just

builds up a rate of descent when slow and then mushes when the wings

are tired of flying.

|

Not exactly a rocketship,

the Command-Aire, embodies everything we think of when we

say "antique airplane." |

So, there I was at 1000 feet. Now what? Don't expect glowing

reports of wingovers and eight-point rolls with hammerheads between.

The Command-Aire is not one of those airplanes. The Command-Aire is

a little slice of old-time aviation in which clearing the trees and

giving yourself a vantage point enjoyed by few mortals was simply enough.

Takeoff was indicative of the mode of transportation the Command-Aire

rep-resents . . . it doesn't fly, it floats. Acres of wing endow the

biplane with so much lift that the engine is there only to get it rolling,

only to excite those wing panels with passing air and coax them into

taking man and machine into the third dimension. This is not a ma-chine

that rushes through the air, leaving jagged holes where it has gone

between Nature's elements. No, this is a machine that rides along on

the crest of liquid summer sunsets and gives you all the time in the

world to absorb the thrill and emotion which is flight. This is not

a machine for personal amazement. This is a machine for three dimensional

meditation.

Knowing that no form of meditation was going to get the airplane back

on the ground, I lined up on downwind and obediently brought the power

back, putting the nose down to what seemed to be a reasonable

attitude. The airspeed indicator didn't move! Knowing how big, dirty

biplanes of the era loved to assume the glide angle of a mapleseed,

I made my turn onto base leg a little shorter than usual so I wouldn't

have to depend on too much power to get me to the threshold. Turning

final, I instantly saw I had underestimated the airplane's desire to

stay in the air. In no way was it going to fall out from under me and

come streaking towards the grass alongside the runway. If I expected

to get it down, I was going to have to force it down. I set the Command-Aire

into a sideslip and watched as it inscribed a straight line through

the air towards the end of the grass runway.

HAVING NO IDEA WHAT THE CHARACTERISTICS would be in the flare, I straightened

out just a bit high and crept the power lever forward to feed a few

hundred extra rpm into the prop. As the edges of the runway came into

view, I leveled off at a prudent altitude and the airplane came to

a semi-halt in the air. It was at that point I realized I was several

feet too high and was about to make my usual vertical descent onto

the ground a little more vertical than desired. A little more power

softened the whole affair and those giant wheels and the long stroke

landing gear let me settle onto the sod with my dignity more or less

intact. The next landing went much better, although I still broke the

glide too high and had to nurse my way back to the ground.

In all honesty, the Command-Aire C3C-AT is not the kind of machine

I'd want to own because I'm born of a different age . . . an era in

which fire and brim-stone performance is often preferred over mood-elevation.

But that's my problem, not the airplane's. The airplane is a fascinating

combination of mechanical motions that say much for Voellmecke and

the Cornmand-Aire Company. They built a fine, solid airplane

that could hold its own against many of its peers and, in fact, flies

much better than many of them. With the success of the Rocket Racer,

it makes one wonder what else Voellmecke may have had up his sleeve

had the company been able to ride out the Depression. Perhaps today

one of the big three would be Command-Aire, and it would be an aviation

household word. Unfortunately, that's not the way the story was writ-ten.

Today, the Command-Aire exists as a single-line entry in aviation's

obituary column of those who have come and gone.

COMMAND-AIRE 3C3-AT

Span ..................................................... 31 ft 6

in

Length ................................................... 24 ft 8

in

Height ..................................................... 8 ft 4

in

Wing chord ................................................. 60 in

Upper wing area ....................................... 169 sq ft

Lower wing area ....................................... 134 sq ft

Empty weight .......................................... 1284 lbs

Useful load ............................................... 706 lbs

Maximum speed ...................................... 110 mph

Cruise speed ............................................. 92 mph

Climb ............................................ 710 ft first min

Ceiling .................................................. 13,000 ft

Fuel .......................................................... 40

gal

Range ................................................... 450 miles

Price ............................ $5500 (1929), $4165 (1930)

For

lots more pilot reports like this one go to PILOT

REPORTS

|