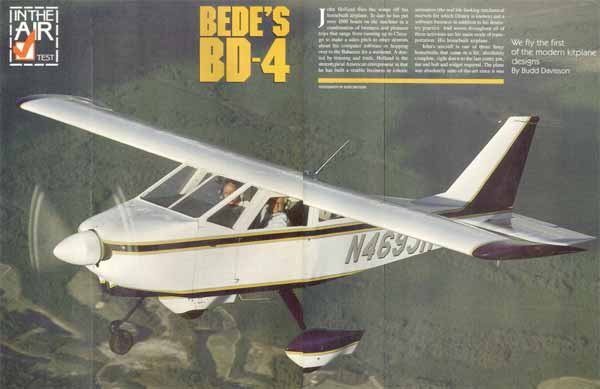

John Holland flies the wings off his homebuilt

airplane. To date he has put over 1,500 hours on the machine in a combination

of business and pleasure trips that range from running up to Chicago

to make a sales pitch to other dentists about his computer software

or hopping over to the Bahamas for a weekend. A dentist by training

and trade, Holland is the stereotypical American entrepreneur in that

he has built a sizeable business in robotic animation (the real life-looking

mechanical marvels for which Disney is known) and a software business

in addition to his denistry practice. And woven throughout all of

these activities are his main mode of transportation: his homebuilt

airplane.

John’s aircraft is one of those fancy homebuilts that came in a

kit, absolutely complete,right down to the last cotter pin, nut and bolt

and widget required. The airplane was absolutely state-of-the-art since

it was designed to be built easy and fly fast.

What's he flying? A Lancair, a Glasair, or any of the other superkits?

Hardly! John Holland's homebuilt airplane that has continually

negated his need for a production craft is a BD-4. This slab-sided, Hershey

bar winged wonder first appeared as plans in 1968 and began showing up

in people's driveways as big kit boxes in 1970. Twenty years ago Bede

was already doing what most of sport aviation regarded as a phenomenon

of the 1980s — the completed kit concept.

|

Both Wittman and Bede had

a knack for making square corners go fast. |

Jim Bede, the hyperkinetic leprechaun from Wichita, was nothing if not

innovative and creative. Bede gave us what appeared to be an endless

string of aircraft designs going from the BD-1 to the BD-10. With all

the furor over the controversial BD-5, it's easy for people to forget

that Bede has had other projects in his life. The various BD numbers

denote airplanes that are almost totally different from one another.

They range from a 65 horse every person's air-plane that eventually mutated

into the Grumman American line to the current dream-bird, the Mach two

BD-10 jet. Like we said, Jim is nothing if not innovative. Also, he pioneered

a large number of structural concepts, the most enduring being

the metal-to-metal bonding which, although hardly taking the industry

by storm, has certainly made the Grumman American line what it is.

The BD-4 is a combination of concepts that are not all that unusual in

designing personal four-place airplanes. It's the way Bede approached

these concepts that made them work. Basically what Jim wanted was an

airplane that must be a good cross-country personal machine, was easy

to build, and had to be a low-demanding machine for the average pilot

to fly. Nothing new here, but it's the way Bede approached

the design that made the airplane so different.

When the concept of cross-country was tossed into the kettle, Bede automatically

said the airplane had to have decent speed and long legs in the form

of lots of fuel. As designed, the airplane was supposed to have from

108 to 200-hp, although the 150s and 180s were the preferred engines.

The 108s were relegated to the two-place role. Sort of the Piper Colt

of the BD clan. The airplane's specification sheets boasted it would

do 175 or 80 with an 0-360 180-hp Lycoming in front. The design carried

52 gallons of fuel in the wings, the gallonage being an easier number

to obtain than the speed, as it turned out.

In the easy-to-build category, Bede broke lots of new ground. The most

obvious being the fuselage structure which used a .063 aluminum

angle bolted together to form a truss work with the skin bonded to

it. The wings were an innovative tour de force — depending on

your point of view.

The spars were almost a Bede signature since they were a large diameter

aluminum tube looking not unlike a piece of irrigation pipe.

Slid down over the brown spars were identical wing sections consisting

of airfoil shaped fiberglass tubs that were open at one end with the

other end featuring not only the rib, but it was joggled to allow the

next "tub" to snuggle over it for a good bonding surface.

The inboard sections of the wing were sealed to act as fuel tanks,

hence the 52 gallons. And this could be increased simply by opting

to utilize any of the other airfoil sections.

In an effort to keep the airplane as easy as possible to build, Bede

worked hard to eliminate those last minute runs to the local airplane

parts store. And to do this, he set up the kits so that they were complete

down to the last cotter pin. The kits were complete down to an engine

which, in 1970 dollars, sold for $5980 with the 150 Lycoming.

It's instructional to think that of the purchase price of

the BD-4 kits, $3-4000 consisted of the price of a 150 or

180-hp Lycoming. Speak of the good old days!

To keep the airplane strong in the easy-to-fly category, Jim Bede once

again stuck to his own guns in utilizing his own personal

definition of "easy!' Bede appears to appreciate the big airplane

characteristics offered through higher wing loadings in that the airplanes

are less bothered by winds and turbulence and the absolute definitive

BD handling package can be seen in the early series Grumman American

Yankees. Actually, as originally conceived, the AA-1 Yankee

was to be the cheapest personal airplane available with the purchase

price being $2500 when utilizing an overhauled 65 horse Continental.

It's a little hard to get a handle on exactly how many BD-4s

have been built but, in 1970, the last time goodold Air Progress ran

a story on the airplane, an excess of 350 kits had been ordered. So it's

fair to guess that maybe as many as 500 kits were sold for a total of

2-300 completed airplanes.

GO TO NEXT PAGE

|