PAGE TWO

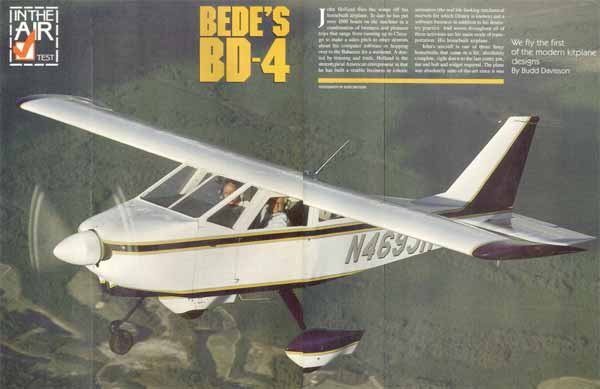

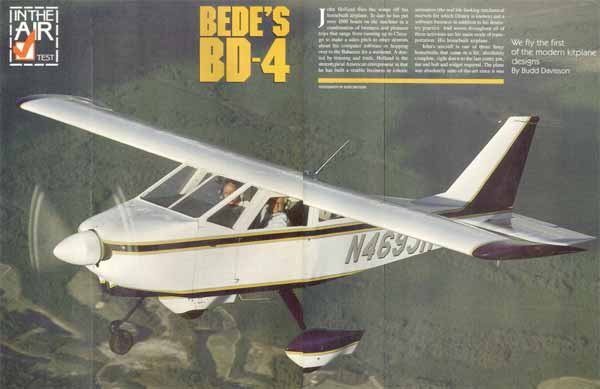

Because John Holland's airplane is always in the process of being used,

most of us ground-bound souls only got to see the plane coming or going.

During one of these comings, I was able to corner John to talk a bit

about an airplane that most of us have relegated the design to the dark

corners of homebuilt history. Since he's a real user, therefore a real

believer in the airplane, he was only too happy to give me a few hours

to fill in a blank spot in my aeronautical knowledge. Most of this information

exchange took place on board N469JH as I got to know the airplane first

hand.

Although John has used his airplane in every sense of the word, walking

around it revealed no areas of deterioration or anything that indicated

any of the new concepts Bede was trying had begun to fail. There were

no cracks where the wing sections were epoxied together, nor was there

any-thing which indicated the fuselage skins were either deforming or

loosening from the fuselage structure. So apparently everything works.

|

Carl Pascarell peaks around

the wing to fly formation with us. |

Boarding the BD-4 was unique because it's not often you get into an airplane

by just backing up and sitting down on the edge of the seat with your

butt and then swiveling your legs inside, putting one of your knees up

to your chin to get around the control stick. Once inside the doors were

closed and the three latches (two at the top corners and one at the bottom

rear corner) were pulled into position to make sure the door didn't try

to spring slightly out of the opening, ruining part of the airplane's

aerodynamic efficiency. I glanced around trying to figure out where everything

was and was amused to find what appeared to be a bicycle handle

sticking forward from behind our heads and above our shoulders. This

was a flap handle, which was simply pushed to one side and pulled down

to gain whatever notch of flaps was wanted.

The trim system consisted of a fat, round gnarled knob that sat between

the seat and a rudder trim which was a Vernier coming 45 degrees out

of the floor under the instrument panel between our collective

knees. The wide flat panel was impressive and although the

fuselage confines appeared to be approximately C-152 in terms of room,

the instrument panel said this was anything but a 152. Not only was

the airplane equipped with dual nav and comm systems, but it also had

a two-axis autopilot, which John uses quite often on his cross-country

trips — especially

when shooting approaches to minimum in the klag.

It was patently obvious when walking around the airplane that the nosewheel

was free swiveling which meant all taxiing was done with the brakes.

While glancing at that unfaired nosewheel, it appeared out of character

with the slick pants on the main gear. This, John pointed out, was

the result of cracks found in BD-4 nose gears and he wanted to have

his out where he could see it every time he did a walk around. Incidentally,

in case anybody has forgotten, there was a time when Jim Bede offered

the ultimate in retrofitting retractable gear — he put

doors on the wheel pants so the doors came down around the tires and

closed them in.

While I was strapping in, John lit the fire on the 180 Lycoming and pointed

us toward the runway. When approaching the end of the runway the seating

position mid-way between the wing made for limited visibility

to clear final. However, the gentle tap of a brake and the BD-4 neatly

turned on one wheel, courtesy of its free-swiveling nose wheel, giving

us a panoramic view of anything that was or wasn't out there. Out in

the middle of the runway the throttle started in and the airplane felt

like it was accelerating quite quickly when, in actuality,

we weren't. And it took a longish amount of time for the BD-4 to work

its way up to the 75 or 80 mph lift-off speed. In all probability the

nose could have been held off and the airplane flown off a little earlier

but with those stubby wings the BD-4 would have a tendency to mush a

little. The 75-80 mph speed John normally used gave a real positive break

and instantly put us into a rate of climb of approximately 7-800 feet

per minute. The takeoff run was long enough that the question entered

into my mind as to how well the plane got off with four people on board.

Best rate of climb seemed to be between 120-130 mph, which put the nose

high enough that it was a serious stretch to try to see over the top.

We were sitting fairly flat in relationship to the top of the cowling

and it just felt more natural to climb out a little faster just in order

to have better visibility.

We leveled out at 3000 feet to test out the controls and found the airplane

to have a feel that is a little hard to describe. This is definitely

not to be construed as a negative comment: Just that it's

a unique feel that can't be compared to anything else. In the first place,

I was prepared for the lack of dihedral to make itself known in lack

of roll stability, but this was absolutely not the case. In doing roll

stability tests, it turned out the airplane was average if not even a

little bit better than average in both static and dynamic. Pitch ability

was also better than average. Although it took four cycles to damp out,

more than half of the speed and altitude differential was damped out

in the first cycle alone.

If there is one sore point to the aircraft's controls, it is the lack

of harmony in regards to the rudder. The rudder is very powerful— so

powerful that at first it is difficult to coordinate smoothly and also

tends to get a little loose in yaw, which would undoubtedly

be tightened up by converting part of the rudder to this area. In all

probability this characteristic is less noticeable on those airplanes

using a smaller engine. On our two different flights in the airplane,

I had a chance to sample the airplane's cross-country capabilities and,

while it did have an unusual control feel, the BD-4 was stable

enough to hold altitude and heading almost unattended — even

in the slight chop we were running through. The visibility as would

be expected was Pacer-like because of the wing, which is not a serious

problem and the seating was good enough to not even be noticeably different

from what you expect in most small two-place airplanes.

In doing the stall series we unloaded in the low 60s. As would be expected,

the stall was a little sharp and tended to roll in one direction or the

other. I had to be very careful and actually study the ball

to keep it in the middle because of rudder sensitivity. However, try

as I may, I couldn't get the airplane to unload straight. The airplane

has a very slight feeling of being either out of rig or slightly out

of line. I couldn't absolutely credit that feeling to anything concrete,

but the feeling was strong enough that I didn't want to do any. accelerated

stalls for obvious reasons.

Running at about 23 square, the airspeed stabilized on 152, which is

almost exactly what John uses for cross-country planning. That's nowhere

close to the 175 or 180 mile an hour figure often banging around about

the design. Couple that number with the ability to file IFR in practically

everything except known icing and feel comfortable, and the airplane

is indeed a serious cross-country mount.

We shot a number of landings and I was impressed to see how speed stable

the BD-4 was in approach and found the two notches of flaps used were

primarily useful for get ting the nose down since they didn't seem to

do much to the actual approach characteristics. Holding 100 mph on final

and then bleeding down to the 90s on a short final, seemed to be a little

bit fast but gave us plenty of time to set the airplane up for a reasonably

smooth touchdown. The pitch rate during flair is very easy to control

and made finding the runway almost fun considering visibility over the

nose was gone, making it necessary to look out to the side as if landing

a Cessna 210 with half flaps. Once the airplane was on the runway it

rolled nice and straight and the rudder was plenty effective until we

got down to a fast walk, at which point the brakes easily kept things

straight.

|

The nose pant is missing

because the front strut has been known to crack and the owner

wanted it out where he could inspect it better. |

John built his airplane in 1975 and it's instructive to look at his machine

since probably very few BD-4s are going to be worked as hard as this

one. Considering the design is well over 20 years old and there are very

few, if any, old wives' tales about the wings coming apart or the skins

delaminating on the fuselage, it had to be said that Jim Bede's concept

does work. However, one has to wonder where all those BD-4s are since

we don't see the type very often. Is it possible they died a lingering

death in the back of someone's workshop, or that they are one of those

airplanes that just quietly go about doing their job and never raise

much of a profile?

Whatever the BD-4's story is, it's interesting to stop and

think this is a kit machine that predates any of the kits we usually

discuss. And the plane is usable in the extreme. Although the structure

is unique, if Holland's airplane is typical at all, it obviously appears

to hold up and offers an interesting variation on today's super-smooth

composites.

Jim Bede has left his mark on aviation. As controversial as he may

be, it has to be said the reason he is controversial is because he

didn't run and hide and go through life in a passive, non-interacting

manner. Whether the rest of the world agreed is neither here nor there,

but at least Jim broke lots of new ground and the BD-4 may well be

one of first original postwar kitplanes. By the time he worked up through

the BD-5, the Wichita munchkin had absolutely proven there was a strong

market for kitplanes, which led to the development of so much of what

we now know as sport aviation. For that alone, we have to thank him. BD

For more pilot reports like this one go to PILOT REPORTS.

|