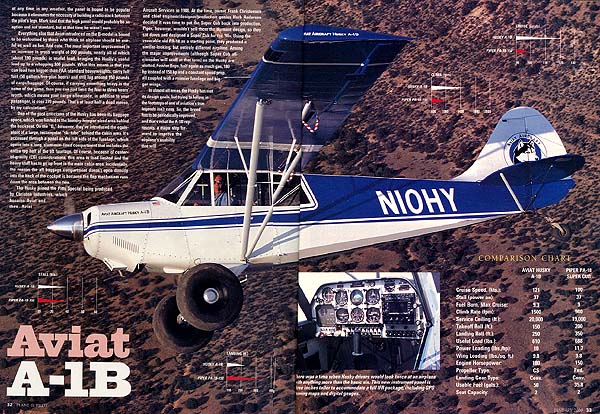

As I came around the corner of the hangar I had to laugh: the folks up at Aviat had arranged a surprise for me. The brandy-new "B" model Husky Mark Heiner, Aviat's demo/test pilot, had delivered down to me had a major podiatric deformity: this Husky had footwear far out of proportion with its size in the form of 31" tundra tires. What a hoot!

I love flying funky little bush birds and especially the Husky, but seeing this one wearing its Alaskan Nike's made me smile. This was going to be fun.

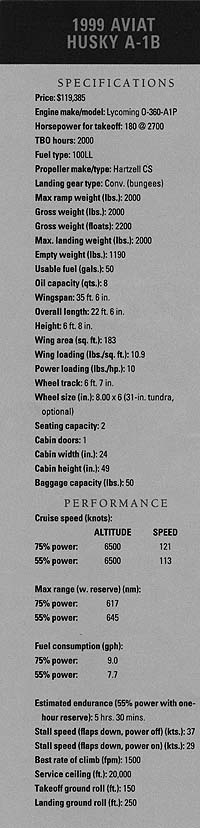

The Husky, in the form I was going to fly it, was the factory's newest with all the latest stuff introduced on the A-1B in 1999. Some of the stuff, like the increased panel height to make it easier to put a full IFR set up in it, including moving map and all the other bells and whistles, is probably open to some debate as to its value to the serious utility pilot. It increases the panel height something like 3" which doesn't really get in the way, but in most utility flying there is no such thing as too much visibility. However, to anyone wanting to set their airplane up to go anywhere at any time in any weather, the panel is bound to be popular as it eliminates the necessity of building a radio stack between the pilot's legs. Mark said the high panel would probably be an option, not standard, but at that time he wasn't sure.

Everything else they intro'd on the "B" model is bound to be welcomed by those who think an airplane should be useful as well as fun. And cute. The most important improvement is an increase in gross weight of 200 pounds nearly all of which (approximately 190 pounds) is useful load bringing the Husky's useful up to a whopping 800 pounds. What this means is that you can load two bigger-than-FAA-standard heavy weights, carry full fuel (50 gallons/5+ hours) and still lug around 150 pounds of cargo/baggage. Of course, if carrying something heavy is the name of the game, then you just limit the fuel to three hours worth (that's a fair cross country isn't it?) which means your cargo allowance, in addition to your passenger, is over 270 pounds. That's at least half of a dead moose by my calculation.

One of the past criticisms of the Husky has always been its baggage space which was limited to the laundry hamper sized area behind the back seat. On the "B", however, they've introduced the equivalent of a large, rectangular "ski tube" behind the cabin area. It's accessed through a panel on the left side of the fuselage which opens into a long, aluminum-lined compartment that includes the entire top half of the aft fuselage. Of course, because of CG considerations, this area is load-limited and the heavy stuff has to go up front in the main cabin area. Incidentally, the reason the aft baggage compartment doesn't open directly into the back of the cockpit is because the flap mechanism runs down the area between the two.

The Husky joined the Pitts Special being produced by Christen Industries, cum Aviat then Aviat Aircraft Services, in 1988. At the time, owner Frank Christensen and chief engineer/designer/production genius Herb Anderson decided it was time the Super Cub be put back into production. Piper, however, wouldn't sell them the dormant design, so they sat down and designed a Super Cub for the '90's. Using the venerable old PA-18 as a starting point, they produced a similar looking, but entirely different, airplane. Among the major improvements (although Super Cub aficionados will scoff at that term) on the Husky are slotted, Fowler flaps, half again as much gas, 180 hp versus 150 hp and a constant speed prop all coupled to a roomier fuselage and bigger wings.

In almost all areas the Husky has met its design goals, but trying to follow in the foot steps of one of aviation's true legends isn't easy. So, the breed has to be periodically improved and that's what the A-1B represents; a major step forward to improve the airplane's usability which will probably lead to still further improvements. There's even talk of a big-engine, four-seat version (did I say that out loud?).

In walking around the new Husky, besides the thigh-high tires and the baggage compartment door on the left, aft fuselage side, the airplane appeared unchanged from earlier versions. Which is to say, the detail work is still superb, especially considering that the airplane is designed to do pick-up truck duty in out-of-the-way places. Clambering up on the big right tire, I backed up and sat on the door sill and pivoted my feet inside and over the front stick. This is part of the graceless entry dance learned by all who fly such airplanes, Cubs included.

Once inside, I was once again reminded how nicely Aviat finishes the bird, but to a guy raised in grassroots bug smashers, the panel was almost overwhelming. This couldn't be a utility bird! A machine meant to be a tool. It was too nice and well equipped. Actually, the panel (which mounted so much stuff, I couldn't identify it all) is indicative of a trend among Husky owners. For every Husky which bounces around nasty little runways in the bush or grumbles into the air with a glider or banner in tow, there are another two or three which are fulfilling an owner's yearning for a classic taildragger that smells new because it is new. Regardless of how well an airplane is restored, there is simply no substitute for new. And many people want that.

As I coaxed the 180 hp Lycoming into life, I had expected sitting so high off the ground to feel strange, but it didn't. For some reason it seemed more or less natural and, with the large tailwheel, there was no change in deck angle.

I elected to make the first takeoff a full-flap, short field number, which is something the Husky does really well and requires little or no technique. Stick full back, stand on the brakes, full power and let go of the brakes. The airplane rolled forward a couple hundred feet, then, while still holding the stick all the way back, a really silly thing happened: with the tailwheel still firmly on the ground, the mains lifted off the ground. The tailwheel didn't leave the ground until the mains were about a foot and a half clear.

Later, we landed in an abandoned piece of flat, high desert nothingness so I could photograph Mark making the same kind of takeoff. It was really impressive because there would be this gigantic cloud of dust and flying cow pies and the Husky would suddenly appear as it clawed its way up out of it.

On that first takeoff, I immediately

noticed something I hadn't expected: the ailerons felt lighter

and quicker than other Huskies I had flown. Mark grinned when

I mentioned it because he says he and the flight test guys have

been slowly fine tuning the ailerons to make them more pleasant.

He was pleased I noticed but it would be hard to miss the difference.

The airplane was never a dump truck, but it was always a little

stodgy feeling in roll and what ever they did to the airplane

has made it very pleasant in the aileron department.

On that first takeoff, I immediately

noticed something I hadn't expected: the ailerons felt lighter

and quicker than other Huskies I had flown. Mark grinned when

I mentioned it because he says he and the flight test guys have

been slowly fine tuning the ailerons to make them more pleasant.

He was pleased I noticed but it would be hard to miss the difference.

The airplane was never a dump truck, but it was always a little

stodgy feeling in roll and what ever they did to the airplane

has made it very pleasant in the aileron department.

We averaged around 1,200 fpm (density altitude was about 7,500 feet) climbing to altitude where I started playing with the airplane. I was ruddering it back and forth when I asked Mark if it was my imagination or when I yawed the airplane, could I feel the big tires trying to fly and pull the nose off center? Again, he nodded. A yaw angle gave the tires the equivalent of a sideways angle of attack and they actually did try to fly. It was a very subtle feeling but it was definitely there and was something I'd have to remember, if I slipped it.

In cruise the big tires soak up at least 10 knots, bringing the cruise down around 105 knots. With their normal 8:00 x 6 tires, Huskies are usually good for an honest 110-115 knots or faster, depending on how much gas you're willing to burn. The POH says 126 knots at 6,500 feet and 75% but not all Huskies are that fast.

I was really looking forward to landing the airplane just to see what those fat tires did and Mark, whom I'd flown with a number of times, didn't lend any advice. He was going sit back there and let me just figure it out for myself. My kind of fun.

We had a goofy little wind that went from being 90° to a tailwind making it difficult to plan an approach and on most approaches I was high requiring healthy slips to get it to come down. I made the situation worse by not being used to airplanes that glide so well. On the first one, as I laid it over in the slip, I could fee the air tripping around the edges of the tires. Again, it seemed to make no difference but it was there, nonetheless. I was holding 65 knots, which was way too fast and I had to work to get it down to 60 where it was much happier. In later approaches, I'd use 55 knots which was even better.

One of my perennial complaints about Huskies has always centered on their bungee trim system. The second you try to pull it off of trim speed you're fighting the bungees. What that has meant traditionally is that as you flared the airplane you'd either have to pull hard against the bungees or, as I usually did, drop your left hand and crank the rest of the trim in.

On my first approach with the "B" model, I dropped my left hand prepared to start twisting the trim wheel backward and found, much to my surprise, I didn't need the trim. I didn't feel myself fighting the bungees as I pulled it into flair. In this respect, it felt like any other airplane. What a change! This was another of the fine-tuning points Mark said they had been working on and I think they succeeded. They have completely eliminated what had been a really aggravating characteristic.

As I held the airplane off looking for the ground in a three-point attitude I didn't know what to expect, however, I didn't expect what I found. The instant the tires touched, I felt myself jerked forward in the seat as the tires tried to stop the airplane. For a fraction of a second, the tires, which weigh 44 pounds each, remained stationary and jerked hard enough at the airplane that there was even a subtle sense of the tail getting light. None of this was anything other than a new sensation and barely needed correcting with the controls, but it was a little weird feeling. What happened next did require some playing with the controls.

The tires, like all tires of the type, carried less than 8 pounds of air pressure and were super soft. When they touched the pavement, part of them stopped turning and part of them didn't so the outside tried to stop while the hub area kept rotating. This caused them to wrap up slightly and, when they untwisted, they shot the airplane back into the air. It wasn't so much a bounce as a slight catapult shot that put me several feet in the air. The airplane dribbled back onto the runway in a series of decreasing bounces and all I could do was sit and watch. It wasn't even remotely dangerous and, even in the crosswind, I was having to use only minimal control to keep it straight, but it sure was embarrassing. The Peanut Gallery in front of Tailwheels and More was full and thoroughly enjoying the show. The more landings I shot, the more spectators gathered.

I'd like to say I figured out the touchdown combination and began greasing it on, but I never even came close. As long as the airplane was on pavement, those tires were going to wrap-up, unwind and put me back in the air. Later, on a gravel and dirt runway, where they were meant to be used, the characteristic totally disappeared because the tires could slide on touchdown.

Aside from the tires lending a different touch to the airplane, I was impressed with the subtle changes they'd made in what was already a good airplane. As tailwheel airplanes go, it's about as fool proof as they come. The only time it demands a little more technique is when landing solo with full-flaps and nothing in the baggage compartment. In that situation it's next to impossible to three-point it because the CG is so far forwards. Partial flaps or as little as 20 pounds in the baggage compartment eliminates that problem.

We hear lots of discussion about the difficulty of landing a tailwheel airplane, little of which is actually based on fact. In the case of the Husky (or Super Cub, for that matter), they require only a modest amount of training, five to six hours for most folks, to be able to fly the airplane safely. More important, those hours become a key to the world of the tailwheel airplane which opens up a myriad of new experiences. In the case of the Husky, the airplane becomes its own key, opening doors to lots of outback adventure. Or, if that's not your thing, it becomes a terrific little airplane that lets you play at flying a vintage airplane knowing every part in it is new.

Aviat has made some worthwhile changes in the airplane and we're going to be watching to see what's next.