As we came upon the lake and began circling in a wide, curving downwind, Dave's voice could be heard over the noise of the rumbling G0-480 Lycomings. Glancing out the left of the airplane, his right hand suspended from the throttles in the ceiling, he was talking to no one in particular.

"I feel like I was born 20 to 30 years too late. I wanted to fly the Pan Am Clippers in the worst sort of way, but by the time I came on line," and, without missing a beat, he reached overhead to turn a spigot and a knob, "The only place we had any flying boats at all was out at Guam and I was just too junior to get out there."

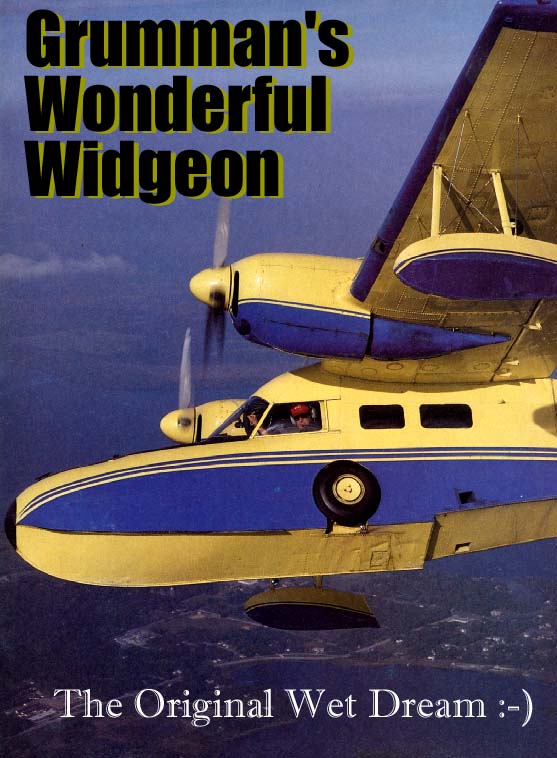

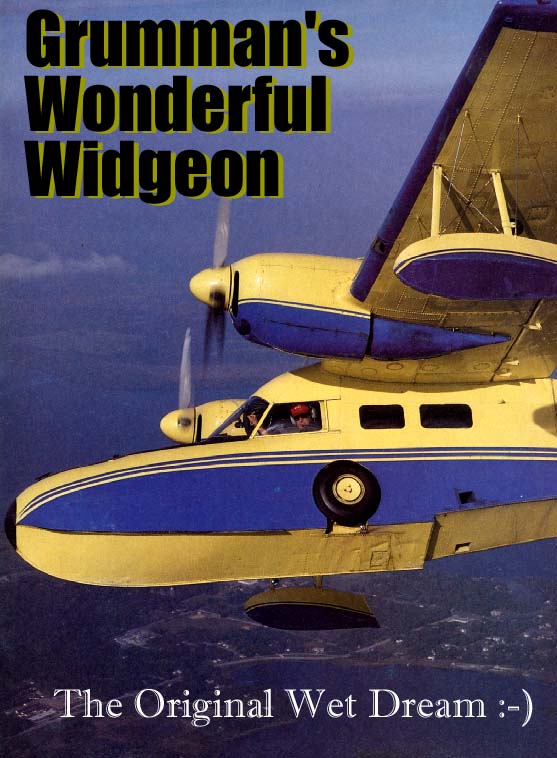

While Dave Garber was reflecting on his desire to have been a captain of one of the mighty China Clippers, he was also presiding over the flight deck of his own mini-clipper. Turning final we lined up into the wind and the tops of the heavy green foliage tried to kiss our hull as we wisked down over the lake's edge to touch its flat surface.

I was sitting in the right seat absolutely spellbound. We were living out one of my fondest fantasies - to be hopping from lake to lake in the fabled Grumman Widgeon. I couldn't take my eyes of the water's shimmering surface as Dave orchestrated the manner in which it gradually filled our windshield, as he maintained a solid 80 miles an hour and felt with his fingertips for the first touch of the keel on the highest wavelet.

The first finger of green water touched the Grumman's bulwark belly, announcing we were about to arrive. That sensation was rapidly followed by many more wavelets and, eventually, fists and hammers as the hull skipped off the higher of the waves before surrendering the lift of the wings to the buoyancy of the hull. We settled into the water like a giant dolphin coming in to relax in shallow water.

The flight was everything I had hoped it would be -and more. Dave Garber will probably never realize how much I had been looking forward to my first flight in a Grumman Wideon. Even if the flight was in a situation where I wasn't capable of making the landing myself, I was still thoroughly capable of appreciating the event.

Garber is in the process of living out many fantasies. A retired Pan Am captain, he has never rested on his laurels for a second, as he has been wildly active in a lot of areas ranging from real estate development to race plane designing and construction. It is the combination of the real estate and the Widgeon that make for a full-blown pilot's fantasy. Dave has developed a still-growing flying community known as Eagle's Nest, not far from Daytona Beach, in Crescent City, Florida, which is certainly not a unique endeavor in Florida. It seems as if every third driveway in that state has a built-on hangar. Dave has carried the flying community concept one or two steps further. In the first place, his compact little community boasts water on one side and a runway on the other with most of the space in between filled with towering pines. Trees and water aren't always part of Florida real estate development.

From a personal perspective, the environment blurs into an unreal reality as you walk out of Garber's door, climb into the Widgeon, which is parked in front of his garage/hangar (which also holds a Nikko Fuji), takeoff and then come around to land in the lake that fronts the house. It's enough to make one ask St. Peter to be reincarnated as a retired Pan Am captain. In fact, of the current homes nestled deep in the woods around the airport, a good percentage of them are occupied by Pan Am pilots. Not a prerequisite, just coincidence!

Besides owning a lifestyle I covet, he has the Widgeon which I have adored from afar since childhood. During the days in which I thought I was building a career, I felt the measurement of my finally "making it" would be the purchase of a Grumman Widgeon. That, I thought, would be the fulfillment of a lot of dreams. Needless to say, I don't have a Widgeon but at least Dave Garber does and is willing to take anybody who severely needs a dose of Grumman amphibian up for a quick hop.

I'm not certain what makes the Widgeon such a siren, but many pilots feel the same. The smallest of Grumman's line of ironworks amphibians, the G-44 first took to the water and then to the air in July 1940. Exactly what its market acceptance would have been had the war not come along is unknown. The armed forces, however, certainly saw the machine as a do-all, be-all utility/officer's transport and over 225 were manufactured for the military. The Coast Guard was the first to jump for the airplane with the J4F4. Even the Army Air Corps bought them as the OA-14. In 1944, the Navy took a full 136 examples into inventory as J4F-2s. After the war, about 50 of the airplanes were built as G-44As for the commercial market and the French hammered out another 40 examples, most of which wound up back in the US bringing the total to approximately 310 airplanes. Dave estimates about 35 are still flying in the States.

We must remember one fact about those original Widgeons: Grumman didn't have the big flat Lycoming or Continentals available in 1940 that we take for granted today. The size of the airplane wasn't such that it would easily accept the 450 Pratt & Witneys of its bigger brother, the Goose, so they didn't have a lot of choices. Because of the limited availability of engines in the right horsepower class, all of the Widgeons to roll out of the factory doors were equipped with a matched pair of Ranger 6-440C-5 inlines, which put 200 questionable horses on each side. To make matters even more marginal, the Rangers were supposed to propel the airplane through a pair of fixed pitch wooden props, which were almost immediately replaced by fixed metal jobs. Pilots familiar with the Ranger and the heft of the Widgeon generally walk away shaking their heads in amazement. The inevitable comment has something to do with what a toad the airplane must have been with those anemic inline engines.

Anemic or not, the 400 horse Ranger Widgeon was about the only way a fledgling wetback could get his multi-engine sea rating, so many a log book has Ranger down in the power-plant column. For its day, the Widgeon was a respected airplane.

Almost as soon as there were a bunch of surplus Widgeons on the post-war market, the bigger horizontally opposed engines also were developed for airplanes such as the Navion. But some folks couldn't wait for the development of just the right engine and Pacific Aircraft Engineering Corp. developed a conversion that hung a set of 300 horse R-680 round Lycomings on the Widgeon ($89,000 for the conversion in 1950s). This I always considered to be the definition of the word "classic." Dave Garber, however, burst my bubble when he said those big old seven-cylinder boat anchors did little more than increase the airplane's fuel consumption.

It wasn't until McKinnon, Singer, Franklin and other conversion outfits came along with the Lycoming GO-435s of 260 hp that the Widgeon was able to show what it could really do. Eventually the GO-480s with 270 hp became the McKinnon standard. With that many horses on each side and not much more frontal area that it originally had, the Widgeon was ready to go to work.

When the airplanes came out of the military inventory there were a lot of eager pilots waiting with money. Oil companies especially seemed to like Widgeons since they could carry executives and equipment into relatively small areas. Businesses seemed to like the versatility of the amphibian concept, as well as the six-place cabin. The Widgeon was a mini-business liner that wasn't afraid to get its feet wet.

Landing on water is one of the most structurally punishing episodes an airplane can go through, even if the plane is designed for such an event. Hitting the water at 80 miles an hour is the equivalent of touching hard grass or concrete at the same speed, which is one reason the old Widgeon and other amphibians from the Bethpage Ironworks were truly built like bridges. Glancing around every part of the G-44 shows a prodigious number of big rivets in close proximity - all following the center lines of an enormous number of structural members; one reason why the Widgeon has reportedly never had an AD of any kind other than for the normal corrosion inspection.

For an amphibian, corrosion is like a creeping cancer - something that always has to be watched. This is especially true for an amphibian that has been worked in salt water; regardless of how well it is taken care of, the plane still faces a life of never-ending inspections and corrosion treatments. This is one reason Dave bought his airplane. Since leaving the factory in May 1945, this particular Widgeon had seen little or no salt water use. Originally bought by a steel company in the Northwest, it gradually followed the rest of the Widgeons to Canada, where it spent the next 25 to 30 years earning its keep under the CF-KPT registration. Garber bought the Widgeon from an airline in Deerlake, Newfoundland, that was converting to land planes. With the exception of a little corrosion cleaning, the airplane was almost exactly as it is seen today.

But all of that is rhetoric. Aeronautical dreams are composed of flights, not walk arounds. I have to admit to more than a fist-full of goose bumps when I swung open that peculiar little side door and walked up between the seats to the flight deck.

The Widgeon (at least this one) is unique in that there is no bulkhead separating the flight deck from the passenger compartment. Rather, there is a seat back high wall giving a colonnade effect so the passengers can see out through the windshield, should they desire. Perched on the top of the colonnades are a pair of fans which Dave said are necessary to keep the air moving around in the hot Florida summers.

The journey from the hatch to the flight deck is probably no more than 12 or 15 feet but it bridges a lot of years. Settling into the copilot's seat, I first glanced and then grinned. Everything about the airplane says: 1) it's a near-antique, 2) it's a Grumman, 3) it's an amphibian.

You can tell the Widgeon borders on being an antique because although its panel is rather sparse - areas above the windshield and behind your head are covered with polished wooden knobs and levers that speak of a different era. You can tell it's a Grumman because, besides saying that in the middle of the polished oak wheels, every exposed piece of aluminum is festooned with generous rivet heads, while only a casual glance at the overhead says amphibian. The dual throttles and prop levers hang from the middle of the roof and the bulkhead behind our heads was littered with fuel tank switching levers and various circuit breakers. The Widgeon's a monument to the amphibian designer's efforts to keep all of the control systems linkages to a minimum by keeping them as close to the wing as possible. As we settled into our seats, Dave dropped the checklist into his lap and began running through the various items as the big Lycomings coughed into life. Bringing up the power on the outside engine we gently swung around to taxi down the center of Eagle Nest's grass runway, which cuts its way through a narrow neck of trees and, at first glance, seems almost too narrow to let the Widgeon pass through. Runup completed, Dave pointed the nose down the runway and I asked whether the Widgeon had a locking tailwheel. He answered in the affirmative, but he almost never uses it since the airplane is so docile. Throttles forward, we began lumbering down the grass at an increasingly brisk pace the tail lifting air almost as soon as the power was up.

Not having a set of rudder pedals, I watched the nose and Dave's feet almost at the same time and saw he was literally steering the airplane down the runway on its main gear rather than having to fight to keep it straight, as with many tailwheel airplanes. Coming off the ground at 80 mph, we settled into an easy 110 mile an hour climb which timed out to just a shade over 1000 feet per minute with three-quarter tanks and two souls on board.

Once in the air, Dave unpinned and rotated the throwover yoke into a pair of hands that had been waiting 35 years for that opportunity. Considering that so much of my flying is in tiny little bumble bee biplanes, I was surprised at the anticipation and excitement with my hand hanging on the throttles and the other one wrapped around the yoke of such a relatively big airplane.

But this wasn't just any airplane. This was a Grumman Widgeon. This was an airplane I had had daydreams about rumbling across the north country in search of adventure or exploring hither-to untouched regions of the Amazon (most of which have now been burned to a crisp). This was the airplane that was supposed to mark my entry into successdom.

Because of the airplane's age and size, I had anticipated a problem with not having any rudders because so many birds of its lineage have the adverse yaw of a river barge. It took only one or two Dutch rolls to realize the airplane has very little adverse yaw and has delightfully smooth and surprisingly responsive ailerons. While the logical part of me had not expected this type of control response, the emotional part had. Fantasy airplanes never fly like trucks, even if they are built like one. The only truck-like factor in a Widgeon is its stability: in that area it bears a striking resemblance to a Peterbuilt in a parking lot.

We were indicating about 160 miles an hour and I asked Dave what he normally flight planned. He said he always assumes 165 miles an hour at 34 gallons an hour fuel burn and is almost always right on the money. Considering the size and bulk of the machine that is not bad Those numbers put the Widgeon in the same efficiency category as its ground-bound peer group known as Winnebago's.

Giving the airplane back to Dave, he pointed it at the aforementioned lake and let me experience THE EXPERIENCE: My first landing in a Widgeon. But if the first landing was neat, the takeoff was something far on the other side of rambunctious fun. In the first place, the airplane has a pronounced tendency to punch the left float into the water on takeoff, producing some rather annoying results. Dave's approach to that is starting the takeoff with the control wheel full right to keep the left wing up and to initiate a turn of about 30 degrees to port. Using this method, the left float stays high and dry.

The instant the throttles are put forward Dave should have his Captain Nemo hat on because, for a few brief seconds, from the cockpit it looks as if we are totally submerged as the bow waves break over the nose totally obscuring all forward vision. In heavy seas this aircraft must be a real Nautilus during the early parts of takeoff.

After a few seconds, the nose finds the top of the water and plunges forward until it is skipping along the top of the waves. Liftoff comes at 80 miles an hour - exactly as it does on land and that speed is achieved in about 15 seconds.

One of the most surprising aspects of the takeoff is the deck angle. As soon as the Widgeon is off the water, maintaining climb speed requires sucking the nose up at what seems to be a wildly exaggerated angle - letting us easily clear the trees on the far side of the lake. I had not expected this kind of performance.

We went through the water initiation/christening routine several times, each time being more fun than the last. So, it was with a great amount of frustration that we had to give up our splashing around for the day and head back to the now mundane grass runway of Eagle's Nest.

I would like to say that I have flown a Widgeon but I can't. I can say that I have flown in a Widgeon but, more importantly, I can say that I have "experienced" the Widgeon. I can also say I absolutely love the plane. With any luck, some time in the future perhaps I will have the opportunity to go for a multi-engine sea rating in a Widgeon and at least live out that part of a lifelong fantasy. If not, Dave Garber has given me the opportunity to at least sample a little of what I already knew I had been missing.