You know those airplane in the barn stories we all keep hearing? You know, the guy, who knows the farmer, who has a cousin, with a friend on the other end of the state who has a warbird/antique/classic (insert airplane of choice at this point) in an old barn and will let it go for a song. When you track it down, if there even is a barn, much less an airplane, it usually turns out to be a C-172, or something similar, rolled into a very tight ball.

However, when Alan Buchner's eyes adjusted to the dark of that barn in California, it was an entirely different story.

"It was a great big, old wooden barn with two side shelters on it." He's gotten so used to telling the story, he no longer marvels at it, but his listeners eat it up. "They used it to store threshing machines during the winter, so they needed all the floor space they could get. That's why they took the airplane apart. To make it fit."

"The fuselage was standing on its nose in the corner with the tail still on it. The wings still had cover on them and were leaning up against the wall right next to the fuselage. It took up practically no floor space that way. "

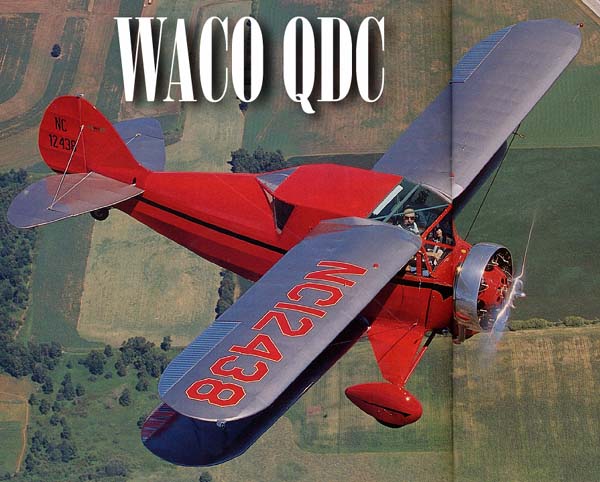

The airplane, which was still dressed in tattered rags, was none-other than an ultra-rare, 1932, QDC WACO. As with most airplanes found in that condition, the last owner hadn't intended for it to remain there for so long. In this case, the years dragged on until the airplane had been sitting for 15 years when Alan first laid his eyes on it.

"Apparently a duster pilot had owned the airplane and flew it a few times when the engine quit and he landed in an alfalfa field just a short way from the field. They towed it back, took it apart and it sat that way from 1954 to when I first saw it in 1969."

Naturally, the most instinctive reaction in finding an airplane in that kind of situation is to try to liberate it for as small an amount of cash as possible. And Alan tried. And tried. But was unsuccessful.

"I tried to buy it from the fellow for three years. But, he just didn't want to part with it. Then, without telling me, he sold it to a crop dusting mechanic who was a friend of mine."

Alan tells the story

with no disappointment in his voice because it all worked out

just fine in the end.

Alan tells the story

with no disappointment in his voice because it all worked out

just fine in the end.

"He kept it about a year and then had to move. He came to me about the airplane and I wound up with it."

During the year the object of his affections was in the hands of another, the time wasn't wasted because the temporary owner took the wings to Vern's Wing Shop in Bakersfield and had them completely rebuilt.

"The wings are almost completely new," Alan explains. "They used some of the spars and a few other things, but most of the rest of the wing wood was replaced by the time I got the airplane."

The wings may have seen some tender hands, but the fuselage was almost exactly the way Alan had first seen it in that dark barn. Besides the obvious deterioration of the years, the airplane had been used, abused and modified as it earned its keep before being abandoned. Many things had been changed and the very identifiable QDC rear windows had been faired over and eliminated, although the term "...faired over..." may be a little too gentile.

"The rear window area had originally been framed in wood but someone removed all of it and used small diameter water pipe to replace the framing. Some of it still had the threads on it! It was pretty crude."

"The QDC was the first cabin airplane WACO produced and those rear windows were one of the ways the factory had tried to make folks used to open cockpit airplanes feel comfortable. Factory brochures said the passengers could look all around just like the F-2 series open cockpit airplanes the QDC came from."

"Basically, when they designed the airplane, all they did was take the wings, tail and engine of the F-2 and build a new fuselage. That was in 1931 or 32. But, I had to get those windows right to have the airplane look right."

Alan is quick to give credit to his friend Tim Kendall for his help in getting the wood right.

"Tim is a model builder, a good one, and that's the kind of standards he used when he helped me reconstruct the rear window framing and other parts. He did everything to the thirty-second of an inch which is much better than they were originally."

Although Alan credits

Tom Fox of the WACO Club for rebuilding the corrugated ailerons,

Jim Alan, Fresno, California for building the aluminum wheel pants

and Terry's Upholstery Shop for the threads, the rest of the airplane,

every bit of it, is vintage Alan Buchner. Actually, it's vintage

Buckner family, since his wife of 34 years, Connie got in on it

as well.

Although Alan credits

Tom Fox of the WACO Club for rebuilding the corrugated ailerons,

Jim Alan, Fresno, California for building the aluminum wheel pants

and Terry's Upholstery Shop for the threads, the rest of the airplane,

every bit of it, is vintage Alan Buchner. Actually, it's vintage

Buckner family, since his wife of 34 years, Connie got in on it

as well.

The Buckner family is a second generation aviation family on both sides of the marriage. Alan's dad started flying in 1927, no doubt enthused because of the exploits that year of a fellow named Lindbergh. He worked through his ratings, which, to hear Alan tell the story, didn't take very many hours, and set up his own flight school and flying service which he operated until he retired. As part of that business he flew charter, including ferrying hunters and fishermen into remote bush strips in the California mountains.

"When I started working on the airplane seriously in the 1980s, I started tracking down the original owners," Alan tells this story a lot too because it is one of his listeners' favorites. "I was running down the list of owners and then came to 1938 and owner number five. It was Les Buchner, my father." At that point he can't help but smile.

"Dad operated the airplane as a normal charter airplane and, when I bought it, he had no idea it was one of his old airplanes."

The urethane paint scheme (over Stits) Alan put on the airplane replicates as closely as possible the way the airplane looked in 1938 when the airplane was in the employ of Alan's dad prior to the war.

"We have a bunch

of old photos from that period and in sanding down through the

layers of paint on the metal surfaces we were able to verify the

colors and paint scheme."

"We have a bunch

of old photos from that period and in sanding down through the

layers of paint on the metal surfaces we were able to verify the

colors and paint scheme."

In walking around the Buckner's WACO it is important to remember that it is an airplane that was done almost entirely by the two gracious folks who stand beside it answering questions. That includes replacing all of the metal work themselves. That's one reason it took nearly 15 years for them to finish it. They had to complete it in the narrow niches of time left between making a living and raising three kids and then minding to grand kids.

Alan makes his living the hard way, one piece at a time, as an A.I. doing annuals on "...primarily Cessnas with a few Pipers tossed in..." He'll also do an occassional restoration, if asked. What that means is the thousands of hours he put into the QDC were either before or after work, which accounts for the many 14 hour days Connie remembers so well. And which she so willingly accepted because the Buckners are obviously a team as well as a couple. She showed more excitement than Alan at being at Oshkosh.

But then, after logging nearly 24 hours getting to the Convention, maybe Alan was just too tired to be excited.

"We worked right up to the last minute finishing the airplane. In fact, when we departed Fresno for Oshkosh we only had four hours on it."

"We went by way of Branson, Missouri and Troy, Ohio where we sat in the rain for three days at the WACO fly-in, then on to Oshkosh."

As he relates the experience, it appears one of Alan's proudest achievements is to have the airplane sit in the rain for three days and not have a single leak in those yards and yards of window fairings.

The Buckners went to Oshkosh as part of the largest WACO assemblage the Convention had ever seen but they were far from being lost in the crowd. The QDC's undeniably unique lines attracted crowds all week. But the crowds were shared with the airplane parked right next door...the only other QDC still flying. The entire population of QDCs was parked stubby wing-tip to stubby wing-tip.

After all those years

of living with the airplane, Alan and Connie are anxious to show

it off, especially in the air. So, when I put that soft, fuzzy,

gee-whiz look on my face, they recognized the signs and started

clearing away chairs and tie down ropes to take me flying. They'll

never know how hard I've worked to perfect that look.

After all those years

of living with the airplane, Alan and Connie are anxious to show

it off, especially in the air. So, when I put that soft, fuzzy,

gee-whiz look on my face, they recognized the signs and started

clearing away chairs and tie down ropes to take me flying. They'll

never know how hard I've worked to perfect that look.

You're just in the process of stepping through that big door into the soft, mohair interior when you're struck by how bright the cabin is. Most cabin bipes, actually all cabin bipes, have a closed-in feeling. Their cabins may be huge. But a little dark. The QDC, however is like an upholstered greenhouse. The windshield works its faceted way up past the main spar to a nearly all glass roof. There is only a short area that is not glass, before the rear windows begin. The overall effect is incredibly cheerful. However, the solarium effect and heat stroke potential is obvious. A pilot could fry his brains in nothing flat.

Then you notice, or rather have pointed out by Alan, the tiny hook which is still welded to the carry through-over the pilots' heads. He reaches back and pulls a translucent, white window blind forward and fastens it to the hook. It looks for all the world like a garden variety, spring-loaded, roll-type window shade that completely blocks the skylight while letting a great deal of diffused light through. The neat part about the blind is that it is accurate to the airplane. 1930's pilots apparently perspired too.

Sitting in the co-pilots seat you have to look hard to find signs of the 1990s in the airplane. In fact, the only obvious one is a manifold pressure gauge attached to tubing under the panel. Other than that, it is totally 1932. You have to look down on the left cockpit side, behind Alan's left leg where there is a small one inch slot in the upholstery. If you snuggle over and look down, you can see the face of a radio and transponder mounted vertically behind the upholstery panel looking up at you. It is far from convenient to use, but it is practically invisible.

As the Continental 220 hp, R-670 (the original Continental was replaced in 1946 because it was such an early version) cranks over and that sound so identified with radials coming to life rumbles back through the codkpit, you suddenly realize the engine is only a few feet in front of you. If it weren't for the windshield, you could literally lean forward and touch the cylinders. This is when the F-2 lineage is noticeable, since that's the way it is in the front pit of that earlier airplane.

With the windows cranked down, elbows on the sills we worked our way past admiring stares to the runway. During taxi Alan scoots up the seat so his butt is half way up the back which allows him to see over the nose.

Since the wheel is of the throw-over variety and there were no brakes on the right side, obviously I was going to have to get a passenger's-eye view of the takeoff and landing. That's okay. I don't think I was up for making my first QDC takeoff/landing in front of several hundred thousand people anyway.

At full throttle, the engine sounded as if it was barely turning over as we began rolling leisurely down the runway. We rolled several airplane lengths, Alan picked up the tail, then another half dozen lengths later, the airplane floated off the runway. I want to repeat that... it floated off the runway. It didn't takeoff. Or rotate. Or do anything else we associate with modern airplanes. The wings developed so much lift, so early, they simply overcame gravity by themselves and we floated off the runway in a level attitude. The takeoff felt like the airplane looks. Very unique and enjoyable.

As soon as we were off the end of the runway, Alan pulled the pin and swing the big, round wheel over into my lap. Even as my hand curled around the polished wood, I began searching for traffic anywhere I could look, which included staring through the openings between the cylinders because they had no baffles and were right in my face at that climb angle.

The airplane was going up at over 800 fpm so it wasn't long before we leveled out and made our way across Lake Winnebago in search of clean airspace.

Even as we climbed I was conscious of the airplane's lighter-than-you-would-expect feel. Everything about the airplane feels, well, it just feels light. Just the way it felt on takeoff. The ailerons aren't light by modern standards but, when put against its peer group, the pressures are quite reasonable and the roll response is too. It's not a Pitts or even a Bonanza, but it is surprisingly quick. Again, the F-2 is felt.

The airplane needs rudder. Not huge amounts of it, but you can't drive around with your feet on the floor without being aware of your rearend trying to move back and forth on the seat. As with most WACO's, the rudder pedal ratio is short, so you don't actually move a pedal so much as pressure it. Also, keeping it coordinated noticeably increases the roll rate.

We were showing a solid 115 mph at cruise and I asked Alan if that was right. He said that was the exact number he uses for flight planning, which is amazingly fast considering. Considering, I could look out at the bottom of the wing panels and see things like polished brass fuel lines hanging right out in the wind on their way to the engine. It's big. It's blunt. It's aerodynamically dirty. It's also fairly fast. Its looks are deceiving.

Power-back and wheel hugged to my chest I could see why the airplane was so successful in the old-time bush environment. I never did get the stall to break and the airspeed was hanging under 40 mph while we sagged down hill at something around 500 fpm. With even a hint of power we could stagger along at 45-50 mph all day long and feel perfectly comfortable.

Back in the pattern that slow speed friendliness was again obvious. I flipped the wheel back over to Alan and he came down final at 60 mph to land on the taxiway (18 Left). As we flared and slowed for a wheel landing, it was as if we were coming to a halt before we even touched down on the mains. Then, as the wind went out of the tail I was again reminded of the F-2 as the tail started down. And down. Then down still more until we were again sitting on the ground at the incredibly steep three-point angle of those early airplanes. Because the angle is at, or close, to the actual stall angle of the airplane, a design practice long since abandoned, if something like the QDC is three-pointed, it slows down even more before touchdown.

The Buckner's QDC is more than just an award-winning example of a rare and unique airplane. It is a stand-out example of what built the EAA and the sport aviation movement from the beginning: A family working together to fulfill an aviation dream. Even if they had the finances, which they didn't, to have someone else restore their airplane, they would have still done it themselves. They obviously enjoy the soul-satisfying feeling of achievement that comes from a job well done.

That being the case, the Buckner's should be feeling pretty good right now.

PS

Just goes to prove you can't ignore the airplane-in-the-barn stories,

doesn't it?