|

Tri-Pacer:

Piper's Utilitarian Milk Stool

It

was July 4th, 1959 at Lincoln, Nebraska's now long-gone Union Airport.

The grass of the north-south runway stretched before me and disappeared

in the distance. There was no way I could know exactly how far away

the other end of that runway would prove to be: When Tri-Pacer N8518D

carried me off the far end on my first solo flight, the distance covered

would eventually span a life time. At one end I was a 17-year-old

kid from a small town and all that implies. At the other end I had

become a 17 year old with stars in his eyes who would never look back.

I still remember the smell of that first Tri-Pacer and, although within

the hierarchy of classic airplanes, many put the PA-22 near the bottom,

I don't and never have. And it is more than nostalgia. The Tri-Pacer,

despite its almost comically compact lines, delivers. It will do the

job and today, with nearly 8,000 having been built, 1951-1960, it

may well be one of the better bargains in four-place airplanes. It

is, however, not without its problems, chief among them being some

rather ominous AD's.

Tri-Pacers are old. Of more importance, they are made of fabric covered

steel tubing and therein lies possible problems. Steel rusts. If the

airplane has been hangared most of its life, chances are this isn't

an issue. But most haven't. The primary areas of concern are the areas

covered by the flat metal frames around the door posts, the struts,

strut fittings and the lower carry-through structure in the bottom

of the fuselage. The AD's were issued after a Tri-Pacer lost a wing.

Before buying a Tri-Pacer, have it very carefully inspected by someone

who really knows the airplane. Very few of the airplanes are in critical

condition, but a little paranoia is always a good thing.

Tri-Pacer wings are fabric over an aluminum structure and, other than

inspecting for damage and obvious corrosion, they represent no unusual

problems other than the condition of the covering.

Modern synthetic covering materials (as opposed to cotton or linen)

go under several different trade names but most are a variation of

either Dacron, a polyester, or fiberglass. Dacron materials, if kept

in a hangar are good for years and years, as long as 20 or more. Ceconite

and Razorback can go forever, which can be a disadvantage. Rag and

tube structures should be periodically opened up and inspected. On

a potential purchase, have the covering inspected, again by a pro,

as it can cost every bit of $10,000 to have a decent covering job

done (Ed. Note: that would $15-$19K in 2006).

| |

|

| |

Although the Tripacer's wings are

short, it gets off surprisingly well. |

One of the reasons the Tri-Pacer suffers so much in the eyes of

high-brow purists is its landing gear. The original PA-20 Pacer,

from which the Tri-Pacer descended, was a cute-as-a-bug airplane

which, unfortunately demanded some attention on takeoff and landing.

As soon as Piper hung a nose wheel under it, sales sky rocketed

as the airplane became brain-dead simple to takeoff and land. Unfortunately

the cost paid was that it earned its "milk stool" moniker

because of the near-tripod appearance of the landing gear.

What many of the purists fail to concede however is how well the

airplane performs. If you compare POH numbers you'll see a 1958

160 hp Tri-Pacer will cruise within 4 knots of a similarly powered

1986 172P, stalls four knots slower, out climbs it, lands shorter

and has a much higher service ceiling. It does give up some distance

in the takeoff roll and has 50 pounds less useful load and 7 gallons

less fuel, but it also costs about a third as much.

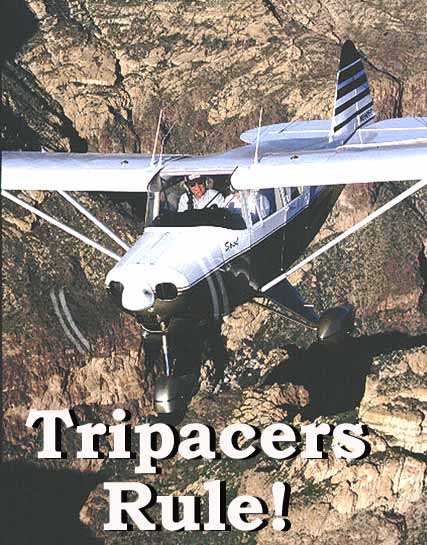

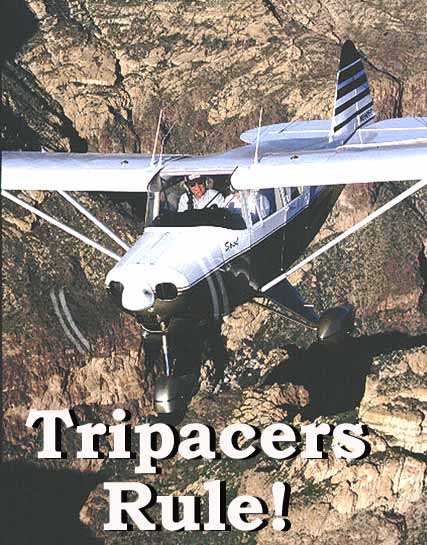

The foregoing is all on paper. The big question is: How does the

Tri-Pacer fly in the real world? To find that out we contacted Stan

Watkins, Executive Director of the Short Wing Piper Club Foundation,

who bases his PA-22-160 at Scottsdale, AZ.

Stan's airplane, Spud, came to live with him in 1990 and it was,

in his words "...ugly as homemade sin..." He had the airplane

painted in Ditzler Durathane and turned the interior over to Paul

Sanchez at Elite Interiors in Portland, Oregon who did it up in

leather. At the same time, Sanchez completely rebuilt the seats

for comfort and Stan says the difference is remarkable.

About the name "Spud." The Watkins family initially referred

to Stan's new purchase as a flying potato. More specifically, an

ugly little spud potato. The name stuck.

One sunny afternoon, Stan taxiied up, put his wife Cheryl, who learned

to fly in the airplane, in the back seat, and the three of us took

Spud aviating.

The Tri-Pacer is one of the few airplanes (I can't actually think

of another) that has a right door for the front seat and a left

door for the rear seat. The upside to that is the rear passengers

have their own door. The downside is the pilot has to be in before

the front passenger. Fortunately, boarding through either door is

actually easier than getting in a 172.

Once inside, the smallish size of the cockpit is exaggerated by

a window area that is smaller than on modern aircraft. For someone

coming out of a four-place Cessna, for example, the cabin is going

to feel dark and claustrophobic. Fortunately, that feeling goes

away in minutes.

The first test while flying a Tri-Pacer is figuring out how to start

it. If a person comes to the breed with no prior knowledge his chances

of getting it fired up are absolutely zero because they'll never

find the master switch and starter button. Unless the airplane has

been converted, the pilot has to reach between his legs and under

the bottom of the seat for both switches.

With the engine cranked, we were ready to taxi. The nose wheel steering

feels pretty much like any other however some people find the lack

of individual brake pedals a little disconcerting. A lever, often

called a "Johnson Bar" hangs from under the panel and

activates both brakes at once. In reality individual brakes aren't

needed for tight maneuvering, as the turn radius with that narrow

gear is so tight the inside wing tip is nearly tracking backwards.

Also, the wings are so short, it'll fit in some awfully tight holes

|

Some Random Personal Thoughts

At this stage of the game I've been flying for forty-nine

years (an unbelievable thought). During that period of time

I've owned a number of airplanes ranging from Cessna 195's

to Clipped Cubs to P-51 Mustangs. Through it all, there has

been this underlying thought, "I ought to just buy a

Tripacer and be done with it." I've always regarded the

airplane as being one of the most practical, and certainly

one of the most cost-efficient ways of getting around. So,

at some point, I'll probably wind up with one. They make too

much sense not to.

|

|

While taxing, I was reminded that Tri-Pacer's came with two basic

instrument panel configurations. The early airplanes had the "low

panel" and have much better visibility over the nose than the

later ones but are cramped for radio space. "Spud" has the

high top panel and is IFR equipped, although Stan seldom uses it as

such.

On takeoff, the 160 hp Lycoming tugged us along with respectable acceleration

which was nice. Tri-Pacer's come with engines as small as 125 hp (fairly

rare) with 135 hp and 150 hp being by far the most common. The 160

hp was on most of the later airplanes and the extra power is very

noticeable. The small engine airplanes are really too under powered

to give solid performance at gross weight. This is especially true

out west. With only two people on board, however, they fly just fine.

| |

|

| |

The 150/160 hp airplanes are much

better suited for carrying four people. Especially at higher

density altitudes. |

Keeping Spud on the centerline during takeoff was an absolute no brainer

and, even though there was a slight crosswind, I don't remember using

my feet for anything. Stan advised rotating cleanly off the ground

at 65 mph or when thenose felt light. This too was a no-brainer. A

gentle tug at the right moment and it stepped into the air with no

hesitation or tendency to settle back on.

I purposely kept a shallow attitude letting the speed build to 80

mph which Stan said was a good speed at our weight. The airplane was

quite speed stable and willing to sit on 80 mph with only a

little trimming. It was the trimming that was a problem, albeit, a

minor one. The overhead trim crank takes a little getting used to,

if only to remember which direction to turn it. 100% of the time I

turned it the wrong way first, even though Stan told me counter-clockwise

was down. Or was it up?

As the airplane settled into a climb, the ASI glued itself to 900

fpm and stayed there until we leveled out at altitude. Considering

that we were three people and full tanks that's not bad for an airplane

everyone makes fun of.

When we leveled out in cruise Stan commented that he really babies

his airplane and purposely uses lower than normal power settings,

around 2300 rpm, for cruise. Also, his prop is a compromise between

cruise and climb. This power setting gave us about 115 mph indicated

which is what he says he uses for flight planning purposes, but almost

always beats that number. Other Tri-Pacer owners report that most

will true out at 120-125 mph at 2450 rpm depending on the prop.

Considering that one of the integral parts of the airplane's unearned

reputation is its short wings and its supposed tendency to imitate

a hockey puck, the stalls are hardly worthy of the name. In any configuration,

gradually pulling the yoke to the stop produces nothing but a soft

mushing and the VSI needle sagging to something around 500 rpm. It's

nearly impossible to get it to break short of a full power, accelerated

stall.

People tend to forget that the Tri-Pacer is a product of the time

when they were trying to engineer required-skill out of the pilot

equation. The Ercoupe was the extreme example in that it eliminated

rudder pedals completely. The Tri-Pacer didn't go that far, but it

did have spring interconnects between the aileron and the rudder so

you could fly it with your feet flat on the floor and still have the

ball centered. It had been some time since I'd flown a stock Tri-Pacer

and I was surprised to find the interconnect wasn't as strong as I

remembered. While rocking the wings with the yoke did cause a little

automated rudder input, it was easily over come to induce a slip,

if wanted. Also, the roll rate is quite a bit higher than I remembered

and higher than a C-172, which I liked.

While cruising around, the visibility is perfectly fine, although

the illusion is that it's less than something like a 172 because everything

in the cockpit is a little closer together. However, if sight angles

were measured, I'd be willing to bet there really isn't that much

difference, if any.

One thing about the Tri-Pacer legend that is absolutely true is its

glide ratio. Notice I said glide ratio, not rate of descent. Yes,

it's coming down a little faster than some airplanes, but it's coming

down a lot steeper than most. Its power off angle of descent with

only one notch of flaps is about the same as a Cessna with the boards

all the way out. This much I remembered and planned the approaches

accordingly.

I brought the power down to 1500 rpm and set up 80 mph as an initial

number intending on going down to 70-75 over the fence. As the runway

numbers started moving down the windshield indicating we were high,

I eased the power to idle and we immediately started sliding down

towards the numbers. We only had 10° of flaps out and it was obvious

we didn't need any more. Stan says he seldom uses full flaps for anything.

I was using the 1000 foot markers as my touch down point and they

stayed rigid in the windshield as we fell at the ground. To a Cessna

pilot, the angle and rate of descent may look high but I think they'd

also sense the rock steady feeling of the airplane in that situation.

There's no moving around or fidgeting. The airplane feels as solid

as a cement block. Right at the bottom, as I started to flair, I cheated

by squeaking on just a touch of power as insurance and bled it back

off as I got deeper into the flair.

The mains touched with an authoritative "thunk" and stayed

there. I was able to hold the nose off only briefly before it too

came down. Then it was carb heat off, flaps up and let's do it again.

I really enjoyed Spud. In fact, I enjoyed just about everything about

the airplane. I'm now convinced that most Tri-Pacer fanatics aren't

bothered at all by the airplane's less than glamorous reputation.

That helps keep the prices down and that undoubtedly suits them just

fine.

|

| |

|