PAGE THREE

|

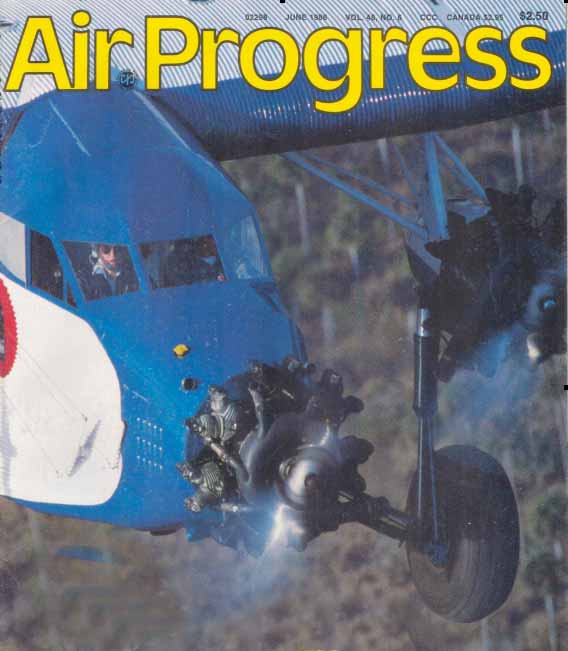

Talk about an airplane having

character! |

Editor O'Leary and Bruce Guberman, our always-famished

camera plane pilot, came drifting past and O'Leary motioned through

the open door to join up. Ed looked over and said (read that: shouted), "It's

you're airplane!" My first thought was, "You've got to be

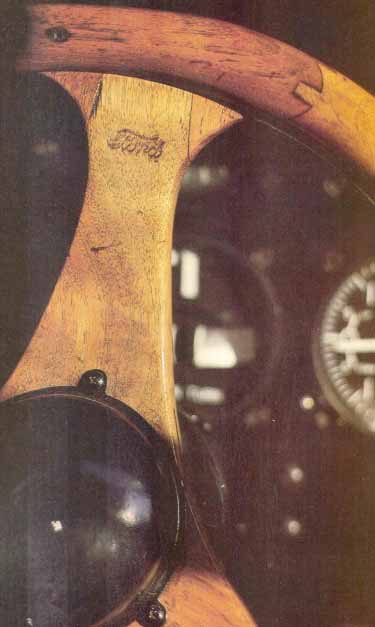

kidding!" He wasn't and my first 45 minutes at the controls of

a Ford Tri-Motor were spent flying formation on a Seneca. Thanks to

Guberman's super smooth formation lead, things worked out

because once I got it in position the Ford's inherent stability took

care of the rest.

What kind of a formation bird is the Ford? Well, remember that Peterbilt

we mentioned? If anybody cares, the really grim looking guy in the

right seat is me. When I concentrate, I frown (and sweat) a lot. Photos

over, I decided to mess around with the Ford a bit, trying to discover

what I could of its personality in such a short time. In flying formation

I found it easy to coordinate and, when I pushed the rudder with no

aileron to check its effectiveness I found out why: Even though you're

perched on the beak of a really ancient bird, there is absolutely no

doubt when you are slipping or sliding. When I tried rolling into a

bank using only aileron, that center Wright J-6 looked really intent

on going the opposite direction. Point One: When flying a Ford Tri-Motor,

you coordinate. Period. If you don't it lets you know about it pronto.

Incidentally, if you want to talk about control response,

don't. The airplane has none. You can move the wheel forward and back

about six inches and roll the yoke 30 degrees either direction and,

if you continue moving forward and back, left and right, the airplane

blithely ignores you. It does absolutely nothing. You have to roll

in the aileron, wait until the airplane catches up with you and then

neutralize. A Pitts it ain't!

Then I brought the power back and hauled the nose up. Or at least tried

to. In a matter of seconds, I found myself with both arms wrapped around

the wheel, hugging it to my chest in an effort to keep the nose from

falling. Then, down around 63 mph, the airplane mushed slightly forward

and that was it. A little power put me back into aviating again and

I tried the same thing in a bank. Same thing happened. I gave the wheel

a bear hug and the (airplane gave me a sink rate of about 1000 fpm.

Power back in and the airspeed returning to its indicated cruise of

90 mph, I glanced left to clear traffic and at the same time caught

some extra faces in my peripheral vision. That's the first time I ever

did a stall series or flew formation with a half dozen people looking

over my shoulder! I had forgotten they were there. They certainly got

their twenty bucks worth! (They were jumpers so only got half of a

ride.)

I NEVER DID GET THE KNACK OF SYNCHING THE props on the three engines.

I understood the concept, but the concept on an old Ford is a lot different

than most multi-engine machines I'd flown. For one thing there was

one extra lever, but that wasn't the problem. The problem was that

you didn't get that rhythmic "beat" you get out of most twins,

when one prop is out of synch. First of all, the tachs are just tired

enough that you set no. 1 at 1800, no. 2 at 1820 and no. 3 at 1850.

That should be 1850 all around. I tried moving one throttle a couple

hundred rpm either direction. I could sense a change in the vibration,

but that was it. There was absolutely no "beat" to work with,

so I tried my best to even out the vibes, but I'm afraid my butt wasn't

in tune with the Ford, so I never got it exactly right.

|

Island Airways operated

a bunch of Tri-motors as school buses for the Great Lakes islands. |

I drove us back onto downwind and saw Ed's hands creep back up onto

the wheel. By mutual consent, he would make the landing. Neither one

of us trusted me with his airplane, which coincidentally, was the last

known working Tri-Motor in the world.

Showing 75 to 80 mph on final, we gradually slowed to 70 mph or so

as we crossed the threshold. On the first landing, I was in the process

of being amused with Ed's rhythmic moving of the wheel fore and aft,

when I felt the wheels touch. We were so far in the air, that left

to my own devices I would have tried to land us another five feet under

the runway. On its main gear, the bird tracked ahead with only gentle

suggestions from the rudder about what it was or was not doing right.

The only part that looked truly tricky or unusual that was after the

tail came down and you had to maneuver it off the runway with the help

of the Johnson Bar. It was a little like using a tiller in a boat at

such a high speed was because we had a forward CG. With the CG further

back, it will go clear down to around 55 mph and keep flying. More

or less.

Ed Rusch continually refers to his blue collar antique as a "Cub

on stilts" and says you ". . . fly it like a Cub . . . three

times!" These are cliches he's used to using, but the funny thing

about cliches is that they are usually true. In this case, they are

absolutely true. The numbers in takeoff and landing are Cub-like and

the three tachometers fit the pattern. When those big airwheels kiss

the pavement, they remind you of nothing but a Cub.

This big Cub has a hard working past that few, if any, single airplanes

can match. Nearly sixty years of age and it is still making its own

way. All we can hope is that the plane continues until it flies past

the century mark. Right now, unfortunately, the barnstorming

Ford's future is questionable. The varied guardians of public safety

have hit it with such important necessities as liability

insurance premiums of $70,000 per ... and rising! This, combined with

the inherent problems of keeping three old-fashioned rubber

bands and an aging body airworthy, presents formidable obstacles.

Damn it, anyway! It would be absolutely criminal to see the barnstorming

Ford relegated to pure antique status. We have a number of them in

museums, so let's keep this one in the air where it should be but not

have it stuck out there like so many antique airplanes are, like some

sort of giant model airplane to be gawked at. This is one of the last

chances so many of us will ever have to see where air transportation

got its start. Our kids today have grown used to Space Shuttles, satellites

and 747s. They absolutely have to know where those all came from and

nothing will brand it so indelibly on their minds as a hop

around the patch in a Ford Tri-Motor. What a travesty it will be if

the combined greed of consumers who can't watch out for themselves,

lawyers, insurance companies and stone blinds bureaucrats slam a door

that presents a truly unique look at our past. Let's hear it for pushing

the retirement age for this hard-working antique into the next millennium!

SPECIFICATIONS

FORD 4-AT-B TRI-MOTOR

Span ............................................................ 74 ft

Length ................................................ 49 ft 10 in

Height ................................................... 12 ft 8 in

Chord at Root ........................................... 154 in

Chord at Tip ............................................... 92 in

Wing Area ............................................. 785 sq ft

Empty Weight ....................................... 6169 lbs

Gross Weight ..................................... 10,130 Ibs

Useful Load ........................................... 3900 lbs

Payload ................................................. 2200 lbs

Maximum Speed ................................... 114 mph

Cruise Speed ........................................... 95 mph

Landing Speed ........................................ 55 mph

Rate of Climb ........................... 750 fpm (initial)

Ceiling .................................................. 12,000 ft

Fuel ................................................... 235 gallons

Range ................................................... 520 miles |

| |

For

lots more pilot reports like this one go to PILOT

REPORTS

|