We Fly Britain's Answer to the Stearman and Like What we Find |

|

|

PAGE TWO

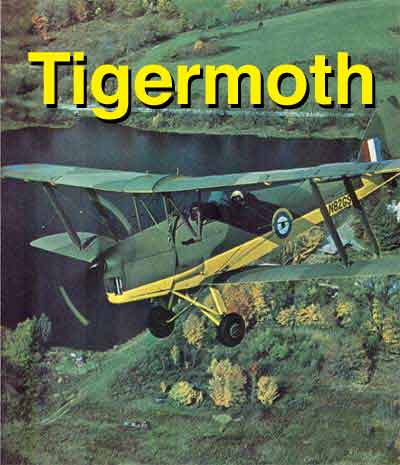

I had great difficulty at first holding level flight because at cruise the nose is at such an impossible low attitude. For such a hefilump of an airplane, the forward visibility is really fairly good in level flight, assuming you ignore the dozens of wires and struts that criss-cross your vision. I also had a tough time holding an exact speed. Even the slightest turn or pitch change grabs speed in an instant, forcing you to drop the nose and maybe even add power. At an indicated 65 knots (which may be entirely wrong because the airspeed indicator was extremely erratic) the countryside seems to almost stand still. It made it easy to see why almost all the photos you see of pre-war aeroclub Moths has them nearly in the trees, hedge-hopping over to some Shiela's house to impress her with the pilot's derring-do. I cannot say I felt comfortable in the Moth. I suppose I'm used to a much more predictable, precise control feel as well as a machine that is less at the mercy of the elements. In the Moth I was up in the air, but that was all. I was "in" the air, moving with it like a chip of wood in a slow moving stream. I didn't like it. I was convinced my destiny was only vaguely in my control. Moving the stick to the left, dropped the left wing, as it should, but the movement of the wing came a perceptible time later than the movement of the stick. The tail surfaces, however, were real control surfaces. They could ram the rear of the airplane around like the outsized flippers of a Disneyland dolphin. ... The

Moth is in absolutely no hurry. It doesn't feel a need to The stall is not deserving of its name. With the stick clear back in my stomach, the slats out (they can be locked closed, if wanted), the airspeed indicator showing zilch, the airplane just moved gently downward, showing it was tired of the game and was going to land, whether I wanted it to or not. Power on, power off, straight ahead, turning, it didn't seem to make any difference. Those big grade "A" bags of lift on both sides of the fuselage just keep on truckin'. I was being extremely ginger with the airplane because it has such a fragile appearance and feel that I was certain any rough handling would litter the countryside with Kent County spruce. Jerry finally took it for a second and racked over into a nearly vertical bank and pulled until the slats were out. With the lift vector pointed in a horizontal direction, the Moth lifted through such a tight turn, that several times I thought I caught sight of our own tail ahead of us. "... The stall is not deserving of its name . . ." I finally clattered my way back into the pattern and brought the power back. On final, I couldn't decide whether my eyes or the airspeed was out of whack. To keep a decent number on the airspeed (50 knots?) required pointing the nose down at a ludicrous angle. But, at the same time, the glide slope was flat enough that I wound up with the rudder in one corner and the stick in the other, slipping down final sideways to get rid of the extra altitude. Then, it was time to flare and everything stopped. I mean just plain stopped!! I don't have the slightest idea whether I hit main gear first, three-point or what because I was so engrossed in watching what wasn't going on that I forgot to notice. We floated down close to the ground, hovered for a second, and plopped down, rolling forward just far enough to leave a short set of tire tracks in the grass. I now know why the English and Canadians call their airplanes "Kites."

As

an elementary trainer, the Tiger Moth was to the British Empire what

the Piper Cub was to us. After the Canadians abandoned their Fleet

Finches in 1942, the Moth was the only primary trainer the RAF and

RCAF used. But, what isn't often mentioned is that the RCAF graduated

their fresh young Tiger Moth pilots directly into the 600-horsepower

Harvard (AT-6). I can see where a Tiger Moth in a cross wind would

make a real pilot out of you as it danced about in gusts and eddies,

but a Harvard? The USAF at least strained our Cub pilots through Stearmans

and BT-13s before we strapped them into AT-6s (during the Korean War

we experimented with the AT-6 as a primary trainer with many exciting

results). I don't marvel so much that the Moth students survived but

I can't help but wonder at the condition of the nerves of the Harvard

instructors. What stories they must have to tell! For lots more pilot reports like this one go to PILOT REPORTS |