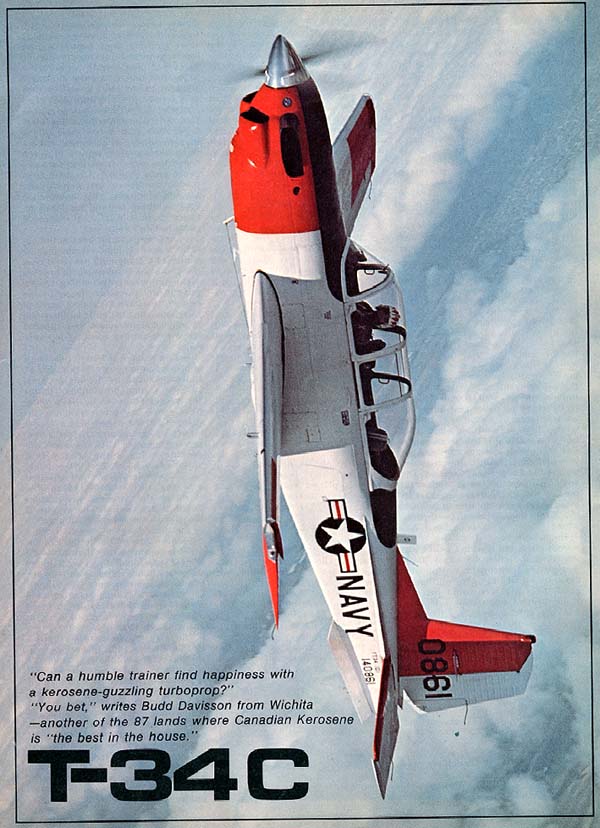

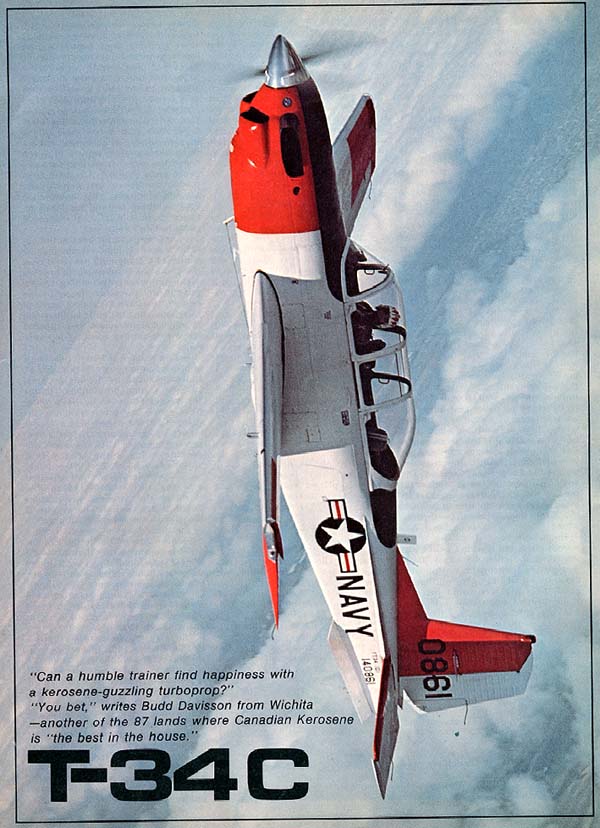

Flying a T-34, any T-34, is an instant no-pain trip into the military world of endless cryptic placards, the snicking of well-designed sliding canopies and the general feeling of going to war at a very leisurely pace. As a trainer the T-34 was, and is, supposed to give a student the feeling of a military airplane with none of the bad habits of its flame-throwing brothers in arms. It is a trainer, period. Despite various early attempts at selling .it as a counterinsurgency gendarme with thirty caliber peashooters in its wings and rockets slung underneath, it is still a trainer. And, if the Navy's reluctance to change to another type of hobby horse is any indication, it must be a darned good trainer.

The gestation period of trainers, especially in this day of design by congressional sub-committee, is extremely long, often of five or ten years duration. That being the case, when a training command finds it's about to use up its airplanes, it had better have a replacement ready. If they wait too long, they're caught between a rock and a hard place as their present trainers come to the end of their fatigue life, and there isn't enough time to design a new trainer from scratch. That's exactly the situation the Navy found itself in recently. Their T-34s were going over the hill for the second or third time and would all be rocking on the front porches of senior citizen homes long before a completely new trainer could be had. So they had to improvise. The obvious choice was to tool up and crank out a few more T-34s and the Navy decided to further extend the mission capability of the airplane by going to a turbine. Naturally, if they'd gone through the usual procurement routine of getting everybody in the industry to trot out a special design, they wouldn't have been able to beat the deadline set by their rapidly dying T-34s. So a few bits of red tape were chopped up and Beechcraft was given a small evaluation contract to modify several airframes and see if the idea would work.

Enter Charlie. Where the rest of

the T-34s were nothing more than straight-tail Bonanzas wearing

soldier suits, the T-34C (Charlie) is designed to be a screaming

demon with missionary tendencies; it will serve not only as a

primary trainer, but in basic as well. Reportedly, the Navy's

idea is to eventually dump all their current T-34s and T-28B and

Cs (hear that warbird freaks?), start a new training program called

the Eagle Syllabus, and use only the T-34C, T-2 Buckeye, and TA-4

for training. Since the military is being forced to keep its training

within tighter geographical confines, the -34 Charlie will give

them twice as much airspace as they had before by allowing them

to work up to 20,000 feet as easily as they did to 10,000 in the

old Bravo models.

Enter Charlie. Where the rest of

the T-34s were nothing more than straight-tail Bonanzas wearing

soldier suits, the T-34C (Charlie) is designed to be a screaming

demon with missionary tendencies; it will serve not only as a

primary trainer, but in basic as well. Reportedly, the Navy's

idea is to eventually dump all their current T-34s and T-28B and

Cs (hear that warbird freaks?), start a new training program called

the Eagle Syllabus, and use only the T-34C, T-2 Buckeye, and TA-4

for training. Since the military is being forced to keep its training

within tighter geographical confines, the -34 Charlie will give

them twice as much airspace as they had before by allowing them

to work up to 20,000 feet as easily as they did to 10,000 in the

old Bravo models.

Anyway, the airplanes that emerged from the first evaluation contract were exciting, but displayed a few minor problems that weren't to the liking of the USN review board. Specifically, Charlie had an aggravated spin mode that once entered, required a very precise recovery method which included first applying prospin controls to bring it out of the aggravated mode and back into a normal spin. Then normal spin recovery technique would stop it. The Navy liked the airplane, but didn't like the spins. Back to the drawing board, and this time all the money being spent was Beechcraft's, not the taxpayers. Still, Beech believed in their airplane and felt the investment was well worth it. After numerous modifications, the final airplanes were pronounced fit for student consumption, and a contract has been signed with the Navy for production of 18 evaluation airplanes with a follow-on of over 200 production aircraft.

A lot of folks are going to think that Charlie is a stock -34B that got the California street rod treatment by simply shoehorning a turbine under the hood. No way! Only the fuselage is vintage -34. Gone are the Debonair wings and gear. When laying out Charlie, the designers moved down to the next shelf in the Beech parts room, to the one labeled Baron, and picked up a brand new beefier wing. Then, on the way out the door, they stuffed a Duke landing gear in their shopping cart. They tossed in some AN hardware, months and months of work in a wind tunnel for spin testing, then stirred it all with a P & W PT-6-24 Turbine and whango! They had a new (but not really new) primary/basic trainer.

One of the things the Navy has learned from flying a generation of trainers is that the old USN method of banging onto the runway a la aircraft carrier is hard as hell on airplanes. So, for the Charlie 34, they asked for and received a guaranteed fatigue life of 30,000 landings and an engine TBO of, are you ready for this, 5,000 hours! The useful life of the airplane is estimated at 16,000 hours which amounts to about 20 years of service. Of course, the only way to guarantee that kind of performance is by overbuilding to the degree that both the airframe and the engine are being worked to a very small fraction of their maximum strength. That's why the Baron wing and Duke gear. The same applies to the engine: 5,000 hour TBOs only come if the engine is loafing, and the only way for an engine to loaf is to be a much bigger one than is needed. The PT-6 they are using can deliver over 700 hp, but the Beech installation uses a mechanical torque limiter to keep the maximum available go-power down to 400 hp. The gear case they're using is good for only 550 hp, so to protect it from damage in case the torque limiter should fail, the fuel pumps will only deliver enough fuel to generate 520 hp. So, no matter what happens, there's no way to hurt the gear case.

As far as that goes, there is practically no way to hurt the engine at all. To keep from over-temping it at an altitude that would allow damaging EGTs, the fuel flow limitation is such that only 96 percent is available at any time. This works out perfectly with the altitude/EGT limitations and lets a student bang it to the wall and just go up and up enjoying the scenery and ignoring the gauges.

One of the major considerations

in setting up Charlie was one of noise. The military has enough

enemies around its training bases without sending hundreds of

students off across roof tops with the scream of turbines deafening

alligators for miles. That's why the PT-6. It's a throttleable

turbine rather than a constant speed unit. It reacts just like

any other engine to throttle commands because the gas generator,

burner section and turbine wheels aren't connected directly to

the propeller gear box. They are interfaced by a couple of turbine

wheels that work in close proximity but don't actually touch,

so when one gets rolling, the other follows but with a slight

lag. All the throttle controls is the gas generator section. The

engine is quiet on the ground, or in the air too for that matter,

so that most of the noise appears to be from the propeller rather

than turbine whine.

One of the major considerations

in setting up Charlie was one of noise. The military has enough

enemies around its training bases without sending hundreds of

students off across roof tops with the scream of turbines deafening

alligators for miles. That's why the PT-6. It's a throttleable

turbine rather than a constant speed unit. It reacts just like

any other engine to throttle commands because the gas generator,

burner section and turbine wheels aren't connected directly to

the propeller gear box. They are interfaced by a couple of turbine

wheels that work in close proximity but don't actually touch,

so when one gets rolling, the other follows but with a slight

lag. All the throttle controls is the gas generator section. The

engine is quiet on the ground, or in the air too for that matter,

so that most of the noise appears to be from the propeller rather

than turbine whine.

The whole concept of the T-34C sounds good, but it wasn't until I was straddling the control stick at 10,000 feet playing fighter pilot on top of a cloud deck that I came to realize how good the basic idea could be. Bob Stone, Beech's enthusiastic T-34C test pilot and chief booster, and I crossed paths twice in the period of several months and I grabbed both opportunities to find out if Charlie was really going to do the job the Navy hoped it would.

Sitting in the front pit, there is little about the panel that will seem familiar to an old T-34 pilot, but at the same time, the advanced instrumentation and avionics packages are the same as you would find in any well-equipped general aviation twin. All the instrumentation is in keeping with Charlie's role of prepping students for the big step up to jets.

Lighting the wick is a simple matter of pushing the button marked "ignition," waiting until the tach works its way up to 12 percent and then advancing the fuel lever to the "run" position. Then the starter button is kept in until the EGT peaks and everything is running.

For some reason, the logic of which totally escapes me, the Navy had Beech do away with the nosewheel steering on Charlie. It's no big deal but it seems like a giant. step backwards for a high powered, propeller driven airplane. So, when taxiing, you're forever snatching a little brake this way or that. However, the idle thrust of the turbine is a bit much for normal taxi speeds so you end up poking brakes now and then anyway. The prop has a beta range and, once you get used to it, you can slow your taxi speed by bringing the throttle around the detent and nibbling at the reverse pitch mode as much as you need to slow down. With the prop in full reverse, it has almost, but not quite, enough push to back the airplane up.

When the tower cleared us to go, I straightened out my left arm and felt, rather than heard, the turbine wind up. The first blush of power is like the runout of a small wave being sucked into the bigger one behind it; but when the big wave arrives, there's no mistaking it. After a moment's hesitation the turbine twists the prop up to speed, and the airplane begins running out from under you.

The view over the nose during takeoff is exhilarating, unobstructed and extremely short-lived. With the throttle to the wall, the truckin'-down-the-runway feel of the older T-34s is replaced by the screaming rush of Charlie sucking up asphalt.

I flicked the gear up and brought the power back a bit while holding 120 knots. Even at that fast a climb speed, the nose is pitched up steeper than you'd expect. With 500 horses, the rate of climb is an honest 2200 fpm, which ain't exactly shufflin'. But, at the usual rated power of 400 hp, I showed only 1500 fpm, which is better than the Bravo models, but only marginally so, and they only had a 225-hp Continental to drag them up. Since both airplanes have almost exactly the same empty weights, the problem must lie in the huge amount of fuel they have to carry to feed the PT-6. The gross weights differ by 1200 pounds, 2975 for the Bravo and 4175 for Charlie.

It really sets fire to the old

aerial taste buds to think how fast a smaller airplane would be

with that engine. At sea level Charlie trues about 190 knots (218

mph) but up in turbine territory, around 18,000 feet, where all

that frontal area and bulk don't hurt so much, it's hopping along

at 240 knots (276 mph). Unfortunately, the sliding canopy arrangement

is nearly impossible to pressurize, so you're up there grooving

along behind a space age engine and sucking on oxygen like a mail

pilot.

It really sets fire to the old

aerial taste buds to think how fast a smaller airplane would be

with that engine. At sea level Charlie trues about 190 knots (218

mph) but up in turbine territory, around 18,000 feet, where all

that frontal area and bulk don't hurt so much, it's hopping along

at 240 knots (276 mph). Unfortunately, the sliding canopy arrangement

is nearly impossible to pressurize, so you're up there grooving

along behind a space age engine and sucking on oxygen like a mail

pilot.

The first time I flew the airplane, I thought to myself, "Boy!

Did they ever screw up the control feel." Fortunately, that

wasn't a lasting impression. Any who have flown the older T-34s

know that it has some of the nicest controls in existence. If

anything, the elevators were a little too "nice" because

they were so light you could easily extrude yourself through the

seat cushions if you weren't careful. Not so Charlie. The elevators

are light but they are still far from the finger touch jobs a

Navy student is going to find in jets.

Fortunately, Charlie still has the obscenely smooth, light ailerons that are the T-34's trademark. Even if you don't use up your quota of four- or eight-point rolls, just doing simple turns is fun. The visibility couldn't be better if you were standing up, and the combination of great visibility and inviting ailerons means you spend a lot of time turning, twisting and grinning.

The spins appear flatter than most airplanes, although that's probably an illusion caused by the high, unobstructed seating position. Bob Stone really seemed to enjoy developing Charlie into the gentle spinning airplane it is today; there was a time it wasn't so gentle, and that's the reason for the unusual twin ventrals under the tail and the long strakes ahead of each stabilizer. The strakes work like vortex generators to energize the airflow over the rudder. Without the strokes, the rudder couldn't get enough energy out of the slip stream to stop autorotation of the spin.

Stone made a Charlie believer of me by grabbing the stick after I'd done a snap roll and sucking it all the way back while holding full power. We were spinning in a very stable, slightly flat appearing spin with full power on and still the rotation speed and rate of recovery didn't seem to change much at all.

The stalls were a real surprise. Charlie obviously has plenty of elevator travel, at least judging from the way it spins, but it acts almost as if it's elevator-limited and can't hold the wing at a critical angle of attack. In any condition, bank angle or gear/ flaps configuration, it shuddered and bucked and fought before it even came close to stalling. The stall itself is more of a mush. Even yanking it into an accelerated stall from a high bank angle produced only a gentle roll over the top into a descending turn in the other direction. Bottom rudder would cause it to tuck under in a banked stall only if it were cross controlled enough to force the ball a full width off.

The landings are as good as in the old models. Maybe better. They've upped the gear speed to 150 knots so they're a good speed brake and come in mighty handy when you want to get rid of altitude. The flap speed is a healthy 120 knots (138 mph).

One thing you find out about Charlie immediately, is that if you are doing much speed changing or jockeying around in different configurations, your left hand is going to be practically glued to the trim wheel. It's a trim airplane, no doubt about it. As a matter of fact, it needs so much trim, so often, that a thumb trim switch on the stick would make sense, except for one thing; the Navy is going to be spinning this airplane with students, who could accidentally catch a stick mounted trim with the right hand, running in a lot of forward trim when they least need it.

Once you're in the pattern and trimmed up, the landings consist of aiming it at the runway, holding 75 knots and flaring gently for some of the smoothest landings you'll ever make. On the other hand, if you want to do it Navy style, you ignore the airspeed completely and concentrate on the end of the runway and the angle of attack display. In this type of approach your angle of attack stays constant and you maintain glideslope with power. From the time you begin the approach to banging onto the runway, the nose attitude never changes, and you hit, literally hit, at the same attitude you were flying.

We shot around 15 landings so I could play with the angle of attack display and I soon found it didn't make any difference whether I cleaned it up on the go-around or not. Completely "dirtified;" it roared up and around just the same as when clean. It was great fun! Bang! On the runway, throttle forward. Rotate almost immediately turning left at the same time. Do a steep climbing 180 to have 500 feet abeam the numbers, dirty up and get "on-speed" by jockeying power and stick to light the middle angle of attack marker. Suck it around in descending 180, glancing at the numbers and the AOA lights, bang, and away we'd go again. We must have been making a circuit every two or three minutes.

As a primary/basic trainer, Charlie has a few advantages over its ancestors which aren't obvious at first. Used in a primary trainer, the turbine virtually eliminates any need for the student to spend vast amounts of time memorizing the credo of throttle management required with the constant speed propeller. Also, power settings are simplified; the prop stays at 2200 rpm, and he jockies the throttle to give the torque meter readings required for climb or cruise conditions. He could actually ignore the throttle and leave it bent forward without hurting anything. In actuality, the only really necessary gadgets he has in addition to stick and rudders are the gear and flaps.

The mechanical torque limiter on the engine is set up so the Navy can quickly turn the screws up to get as much as 520 horses, and those last 120 horses are pure excess horsepower which add a lot of macho to Charlie's personality. So, theoretically, they could begin students on 400 horses and graduate them up to 520 in later phases.

Everything about the airplane aims the student toward the higher sophistication of the jets without burdening him with so many cockpit goodies that he forgets he has to fly the airplane. Charlie has the control a student needs to make the airplane do his bidding, the response of a much higher performance airplane while still maintaining a nice fat margin of error to protect the student. In short: it's an excellent trainer.

If Charlie has any shortcomings, it would be that it isn't cheap. At $300,000 a copy, it's within $40,000 of the Cessna T-37 jet; however, a quick analysis shows there isn't any reason it shouldn't come close to the T-37 in cost. The only difference is that one has pure jets, the other a turboprop.

Another unhappy feature that many Charlie opponents will eagerly point out is that it burns upwards of 40 gallons of kerosene an hour, more than twice that of the old Bravo-34s. However, that's less than a T-28 burns (which uses avgas) and the direct operating costs will be offset by longer periods of maintenance-free flying. With a 5000 hour TBO, a lot of students can go droning around on the same engine before it's worn out. Also, by replacing two airplanes in the inventory (T-34B and T-28) the simplified logistic and supply system should save a few bucks.

As an interim airplane, the T-34C is going to do a fine job.

What remains to be seen is exactly how long that interim is and

what the Air Force decides to do about its own soon-to-be-critical

trainer needs. At any rate, Charlie will be the first friend the

new Navy birdman meets on his way towards the golden wings, and

I think the relationship will work out well.