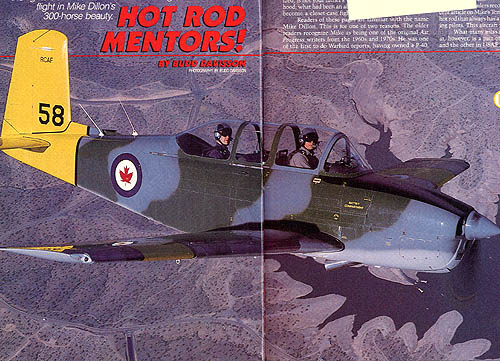

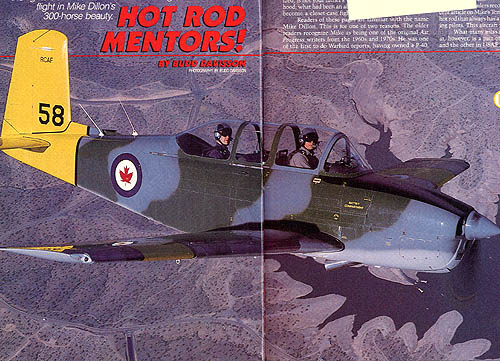

PIREP: 285 hp T-34

As the ragged Arizona desert fell away to become a folded backdrop below and the needle went past 10,000 feet, I glanced at the VSI. It still showed a solid 1400 fpm and we were indicated 120 knots. This, I realized, is not your father's T-34. With 285 ponies under the hood, what had been an absolute thoroughbred trainer had become a closet-case fighter.

Readers of these pages are familiar with the name Mike Dillon. this is for one of two reasons: the older readers recognize Mike as being one of the original Air Progress writers from the 1960's and 1970's. He was one of the first to do warbird reports, having owned a P-40, flown a Bf-109 (and survived) and numerous other high performance birds. He was, and still is, one of the more innovative air-to-air photographers, specializing in mounting cameras at odd places osn the airplane and photographing other aircraft.

Newer readers recognize Dillon from Gene Smith's recent article on Mike's Temco TT-1 Super Pinto, a kero-burning hotrod that always has a pool of saliva around it from drooling pilots. This aircraft is the ultimate personal toy.

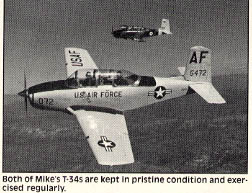

What many miss in visiting Mike's toy room/hangar, however, is a pair of Beech T-34's, one in camouflage and the other in USAF markings. As is usually the case, when other big birds are around, the lowly Beech Mentor receives short shift. When compared to the other Warbirds, it is just a little too mundane. A little too common. And that's a little too bad!

Those who have flown T-34s always have two com-ments about the airplane: First, it has one of the best balanced sets of controls of any aircraft available, feels fan-tastic and lands like a dream. Second, with only 225 hp on board, it is sadly underpowered. The stock Mentor is a beautiful dancing partner with arthritis.

Dillon's T-34s have taken the cure.

The cure for Mentor-arthritis is a healthy injection of horsepower,

which in this case means 285 hp (Continental 10-520) in one airplane

and 300 hp (10-550) in the other. These horsepower injections,

as I was to find out, make the T-34 a Beech of another color.

Dillon's T-34s have taken the cure.

The cure for Mentor-arthritis is a healthy injection of horsepower,

which in this case means 285 hp (Continental 10-520) in one airplane

and 300 hp (10-550) in the other. These horsepower injections,

as I was to find out, make the T-34 a Beech of another color.

It is often assumed that the T-34 has always been a winner. With a PT-6 turbine in the nose it still serves the Navy as a primary and basic trainer and is only just now being retired by the many foreign services that purchased the airplane. However, in the beginning it didn't look as if that was going to be the case. The military bidding procedure has always been fraught with curious twists and turns and the T-34 was the result of one of those.

In 1948, the government put out a bid spec for a new inter-service trainer to replace the T-6 Texan. When the competition was held in 1949, the two primary contest-ants were the Fairchild YT-31 (looks like a taildragger T-28 with an R-680, 300 hp Lycoming) and the lovely Temco derivative of the Swift, the T-35 Buckaroo. Although the Beech Mentor was flying, it wasn't in the contest. When the flying was over, the winner was declared to be the Fairchild design. Then, something happened; it isn't known exactly what, but reportedly squabbling between the services invalidated the contest and it was again reopened. This time a newer version of the Buckaroo was a con-tender, as was the Beech Mentor, but the Fairchild had disappeared from sight. Beechcraft came out of that contest with firm orders from both the Air Force and the Navy. Minor differences between the two services' airplanes resulted in the T-34A for the Air Force arid the T-34B for the Navy.

The two services continued to use the airplanes until the Air Force decided to go the T-37 all-jet route, and the Navy replaced their T-34Bs with T-34Cs in the mid-1970s. What resulted is a huge number of airplanes available for civilian usage. Or at least that's what should have happened. What actually transpired was a convoluted path, in which the airplanes all first went to CAP units, park services, or some other governmental agency because a clause in the procurement contract said they wouldn't be turned loose on the market to compete with current Beech products. When all these recipients realized they had bargain priced airplanes that required the upkeep of a then-new Bonanza, they turned around and auctioned them off to civilians.

For years and years, T-34s languished in the Warbird backwaters. $25,000 was a huge amount to pay for one of them as recently as 1980. But to say things have changed is like saying it drizzled the night Noah built the ark. $100,000 Mentors are commonplace and half again that amount is often required to get a newly restored one. (Editor's note from the year 2,000: Oh, you naive little toad, just wait a few years, buckoo!) In-sane, you say? Possibly, but here is a Warbird that doesn't strain the monthly pocketbook (once it is paid for, that is), doesn't strain the pilot and gives every bit of the mili-tary feeling with a fraction of the usual worry.

My introduction to Mike's airplane was a little on the casual side. My partner, Jim Clevenger, and I were out visiting Mike and mentioned we wanted to go over to another airport to visit Doug Champlin's Fighter Museum. Mike said, "Fine, take 46 Charlie:" After flipping a coin (Clevenger lost), I found myself in the front pit with Mike pointing out all the important stuff. Although I hadn't flown a T-34 in 15 years - and very little even-then -I had absolutely no apprehension because I remembered what an absolute gentleman the airplane was.

Sitting in the cockpit, it is impossible to escape the little bit of excitement which always comes from saddling up a military airplane, even one as docile as the Mentor. Sitting straddle of the stick, consoles festooned with switches, breakers and knobs running down each side, placards everywhere in sight, it just said "military." Probably one of the biggest factors in removing the apprehension that most of us military novices feel in flying birds like this is the tremendous visibility. You sit high in the relatively narrow fuselage and have a commanding view.

Thumbing the boost pump to get fuel pressure and tickling the starter brought the engine to life and I could concentrate on making sure I knew what switch did what for the radios. As Mike mentioned, flying the airplane was the easy part of any checkout, figuring out the avionics is always the hardest.

Trundling out to the runway, I had a first-time experience on this flight, in that it was the first time I ever had to use a garage door opener to get to the taxiway Some of the hangar areas on Scottsdale Muni have security gates across the taxiways which explained the garage door opener clipped to the glare shield.

There is nothing I hate more than trying to find my way around new airports so I told ground control I was new to the area so keep an eye on me. Both ground control and the tower had plenty of patience and shepherded me around nicely. After takeoff, I would test the tower's patience but they handled me without a hint of annoy-ance - which would not have been the case back east.

Cleared to the active, I brought the power up and enjoyed the throaty roar working its way past the David Clark's. T-34s have augmentor stacks that may or may not help the power, but they definitely help the image because of the way they round out the exhaust tone.

Takeoff in a T-34 usually takes a lot longer than it did in 46 Charlie. But even so, they don't differ much from the Bonanza from which the breed was derived. The biggest difference is the increased control, whether perceived or real, that results from sitting on the centerline with a stick rather than a wheel. Loading the stick lightly talked the nosewheel into the air and let the machine run on the mains until it was perfectly happy to fly, which was probably somewhere in the high 60-knot range. Once off the ground, the airplane kept going like it knew what it was doing while I attended to other chores.

Turning right and heading south, I suddenly realized I didn't know exactly where our destination, Falcon Field, was. I knew it was close and I thought I'd be able to see it from pattern altitude, which was not the case. Not one to hide behind embarrassment, I called the tower and asked for a heading to Falcon Field, admitting to being a dummy. They gave me the numbers and away we went.

The flight to Falcon Field was too short to even discuss, but the landing was not. I've flown in the back seat with zillions of T-34 drivers during photo missions, and they all seemed to approach in the 80-85 mph range. So, I figured the high side of 70 knots was close enough. Gear down as we entered downwind, I was again reminded what a fantastically well-behaved airplane this was. Even during configuration changes, it didn't want to do anything unusual. In fact, once I had the flaps out, the approach was a simple matter of jockeying power enough to keep the runway numbers stationary in the windshield. And what an amazing view of the runway numbers the airplane gives.

Breaking the glide in most airplanes is when you get the first hint of what the landing is going to be like. With 46 Charlie, it smoothly rounded out and sat there until plunking down gently on the mains, the nose gear stay-ing clear until I let it down to get the brakes. What a pussy cat! Flying this airplane actually made me feel like I knew what I was doing, even though I clearly didn't.

Later in the day I had time to play with the airplane and mentally record some more lasting impressions, the most important having to do with the curative nature of 60 to 70 additional horses.

In all honesty, I frolicked around in both airplanes during the day (and I can't separate the two airplanes in my mind. They both pointed their noses at 12,000 feet and went upstairs as if horsepower were no problem. This was a noticeable difference from a stock T-34. Another was the 160-165 knots indicated with about 23 inches and 2400 rpm.

There is no part of a Mentor flight in which the pilot isn't aware of the airplane's feel and balance. Yes, it is a heavy airplane, but with the extra horses that isn't noticeable. The ailerons are typically Beechcraft, meaning smooth and relatively light with precise response, and the elevators could almost be termed very light. The net result is an airplane that has a difficult time staying right side up. Rolls of any description are beautiful. The absence of an inverted system stymies good slow rolls, but four-point aileron rolls, big swooping barrel rolls - anything which requires twisting around the longitudinal axis -are pure joy. With the airplane's max dive speed being well into the last half of the 200 mph arc, G buildup becomes the only concern when deeply involved in dog fighting -that and the general location of the ground.

This is one hell of a great airplane for goofing around in.

Unfortunately, nothing about the machine is cheap, unless it is the fuel, when compared to a Mustang. Several companies specialize in doing the 285 conversion but they are expensive. The engine is installed with a sizeable amount of offset, which results in the spinner not being lined up with the cowl, but cancels out most torque effect of the new ponies

The supply of airframes has also gotten tight Actually, there are still plenty of them around,. but the owners are wanting a lot more than the $10-$15,000 the CAP etc. got for them. A recent batch brought in from South America was-reportedly priced in the $100,000 range and nothing indicates the prices are going to level off. This, of course, is generally true of all used airplanes and especially so of special-interest machines.

The T-34 contingent of the Warbirds of America has become a well-organized group riot only for flying, but for the support of T-34s. If at all interested, contact Charlie Nogle, Box 1618, 29 Fields East, Champaign, Illinois 61820.

It is a fact that the T-34 is looked down upon by many of the

big iron owners. More often, however, they have to look up at

the T-34 because it is flying while they are bashing away at cantankerous

mechanical contrivances. The T-34 just keeps on trucking and continues

to prove that it is indeed the Warbird for the masses. BD