When something like this happens," Steve Halpern gestured with

the articulated silver hook that replaced his left hand, "you

have two choices: you can run hide and feel sorry for yourself, or

you can make do with what you have left."

Halpern, who good-naturedly calls himself Captain Hook, was saying

this as we were charging along at 5,000 feet in his mightiest of Swifts.

He punctuated his sentence by twisting into a flawless slow

roll.

|

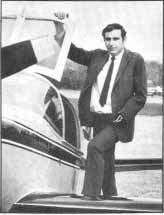

Steve Halpern (35 years ago)

didn't start learning to fly until he lost his arm. Gutsy guy!! |

"...I was helping install a new elevator, when a piece of metal

shot across the shaft and hit me. I woke up in the hospital

with my left arm totally useless from the shoulder down. Eventually,

I’d have it amputated. I was damned lucky to be alive and I knew

it. I had a lot of time to think about those things I'd been meaning

to do, but never got around to. Learning to fly was one of them. So,

as soon as I got out of the hospital, I started taking lessons. I think

the ink on my license was still wet when I bought the Swift. Then it

was still a standard 145 hp."

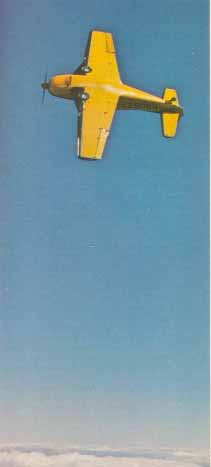

He was referring to the yellow streak we were riding across the sky.

Halpern, of Woodmere, New York, owns and flies what is probably one

of the hottest little airplanes flying today. Outwardly, there is practically

nothing to differentiate it from the standard

Globe Swift. Most people notice the Bonanza wingtips that make it look

like a Bearcat from the bottom, and a few spot the added dorsal fin

and wing root fillets. But practically nobody notices the small round

inlet on the right side of the cowl for the turbocharger or the massive

constant-speed propeller that is necessary to

provide traction for the horsepower factory under the cowling, a 250-hp,

turbocharged Franklin.

This brutish little backyard fighter is usually referred to as a D'Arcy

Swift because the engine conversion and basic airframe beefing was

done by John D'Arcy of Miami, Florida. D'Arcy is one of a whole legion

of Swift nuts who border on being fanatics about modifying

and changing the little airplane. D'Arcy is the most advanced and sophisticated

of the bunch, as he has been competing in aerobatic contests for quite

a few years with hotrodded Swifts.

|

Only the turbo inlet hints

things are really cookin' under the cowl . |

His modification program was not without its glitches, the most outstanding

being the time he pulled a wing off a stock Swift. He was getting ready

to show the 9G capabilities of the airframe to the FAA and was checking

out a new camera mount when he pulled a bit too hard. He didn't realize

how much extra speed he was getting from the 250 hp Franklin.

He caught a glimpse of the G meter going past 11 and suddenly found

himself outside, dangling in his parachute with pieces of

Swift disappearing in the distance. Because of that little

setback, he has completely re-engineered the Swift and beefed-up all

its weak points, making it an airplane capable of any inside or outside

maneuver the pilot cares to try.

Halpern walked me around his airplane and pointed out some of the structural

changes D'Arcy made. Both the top and bottom centersection spar caps

have been strengthened by massive aluminum bars. The outer wing panel

attach points, which failed in the earlier folding-wing-Swift incident,

have been replaced by gigantic steel fittings running well out into

the panels and each panel has an extra rib besides. All the tail spars

are doubled up to take the beating of multiple snap rolls, and the

rear fuselage bulkhead has been replaced by a heavier one with fewer

cutouts.

Halpern was satisfied with the safety of the beefing program, so he

decided to take off on another program, aimed at speed. The Swift,

for all its sleek lines, is basically a pretty dirty airplane. It needs

fillets here and bends there, and Steve decided to supply them. He

replaced all protruding screws and bolts with flush ones, especially

in the windshield area, adding a quick release canopy while he was

at it. He canted the wing leading edges forward, a la P-51, so the

wheels would be flush when retracted. He plans to add gear doors in

the near future. Because of the speed and weight changes, the airplane

flew with the elevators trimmed constantly down, adding

drag, so he's now in the process of changing the angle of

incidence of the stabilizer, and will remove the vertical

tail offset at the same time. It's already incredibly fast, but how

fast is fast enough?

The Franklin 0-350 engine is actually a fugitive from a helicopter

production line, so it's really a bear for punishment. It gets a lot

of power out of a very few cubic inches, so it doesn't like to run slowly.

It's happiest when screaming and the pressure carburetor in the

inverted system doesn't help when on the ground. To keep it from fouling

up, you have to operate it with the mixture halfway out until almost

ready to take off. It coughs and wheezes and sounds as if it's going

to conk out any second.

|

Did we say something about

Hook having fun? |

Taxiing out, fiddling with the mixture to keep it running,

I had the occasion to look around. The interior hasn't been

completed yet, but even so I could see it was still basic Swift, 1946.

The gear and flaps are still those archaic-looking barroom

spigots that make you switch hands on the wheel to operate, and the

circuit breakers, which double as electrical switches, are still mounted

in that innocuous whitish, ribbed plastic that reminds me of early

RockOla jukeboxes. Worst of all, the trim is still mounted behind my

head on the turnover structure and made me risk a charliehorse every

time I twisted around to reach it. About the only things that hint

at what's up front are the new vernier throttle, prop control and a

manifold pressure gauge that goes up to 60 inches. That

certainly looks out of place in a Swift!

I guess the thing uppermost in my mind when I started the takeoff was

torque. This was an awfully little airplane and a mighty big engine.

I screwed the throttle vernier slowly in, or at least I thought it

was slowly.

Every turn of the throttle rewarded me with a tremendous increase in

noise and a smack in the small of my back. It accelerated like a full-grown

fighter and when I pushed the nose down, the runway looked as if it

were going by at a fantastic rate. With that big prop blowing so hard

on the rudder, it was effective as soon as the throttle

started moving. Even so, I didn't need all that control because it

tracked straight ahead. I pulled it off the ground and tried to hold

100 mph while the heavy-duty pump sucked the gear up. My climb-out

angle should have left no doubt that this was not the usual ground-hugging

Swift.

I'd watched Steve take off a number of times and I knew that the combination

of prop and exhaust noise was making the gophers dig deeper holes,

so I reduced power until I cleared the pattern and headed out into

the practice area. Even at reduced power, the cockpit noise

was something to be shouted over. Climbing at 80 mph indicated,

I started timing the rate of climb. The altimeter was going around

at least twice as fast as my second hand and we covered

a good 2,200 feet while the hand made one lap of the dial.

GO TO NEXT

PAGE

|