|

This was written, as the saying goes, "Back in the

Day." Sport aviation was just beginning to take hold and Oshkosh

didn't exist, as the first EAA convention wouldn't be held there until

the month after this article appeared. Antique airplanes were still fairly

inexpensive and parts more available. In fact, most had yet to be restored

even for the first time, as they were still on the first fix-enough-to-keep-it-flying

go around. This must have been one of the first three or four pilot reports

I penned. It's interesting to read my own words over three decades after

the fact. I've edited nothing in this text, so you're hearing the words

of a twenty-seven-year-old writer/photographer just beginning to find

his way. Also, magazines like Air Progress were limited to four pages

of color per issue and the black and white reproduction was awful. Things

in that area have come a long way.

The Reliant was built in the days when airplane was

spelled with a capital "A." People liked to travel

first class, in style, with all the comforts of home. Nobody was

going to go anywhere if they had to suffer discomfort. When the

airplane progressed to the stage where it could offer more than

a rough ride and a case of pneumonia, big business began to view

it in a completely new light. No longer a daredevil machine, it

was now a means of travel. Affluent travelers demanded comfort even

in the air, and so, the cabin airplane started out as a summer home

with wings.

The foregoing philosophy yielded many beautiful ships: the Staggerwing

Beech, the Howard DGA-15, the Noorduyn Norseman, and the Gullwing

Stinson Reliant. Before technology brought this golden era to an

end after World War II, these planes ruled supreme as the original

miniairliners. They were capable of carrying anybody anywhere in

the manner to which they were accustomed.

These queens of the low-frequency airways have become favorites

among the more ambitious restorers. Ambitious, because recovering

a Reliant or a Staggerwing is like trying to recover a house.

| |

|

| |

Although highly tapered wings supposedly

lead to tip stall you can't prove it by the Reliant. Its

stalls are super benign and well mannered. |

Many

of these big birds have come to roost at the annual EAA convention

in Rockford ( Ed: Now this is an OLD pilot report). That's

where I first saw Stinson SR9C, N18439. I heard somebody exclaim,

"Look at that!," and I turned to see an iceberg-sized

airplane lumber into line and take its place among the others. The

normal planes looked small in comparison; the homebuilts looked

like part of her brood waiting for dinner. That's when I felt that

old I'd-sure-like-to-flythat-one urge, not knowing that I'd eventually

get the chance.

The next time I saw N18439 she had migrated east and was the prized

possession of Fred Morris and John Yansura; they kept her at Flanders

Field, in north Jersey. She hadn't lost any of that aura of grandness;

she shone even brighter. N18439 is a 1937 SR9C, the Reliant model

that some purists consider the most desirable.

The model R Reliant was born in 1931 as a redesigned, hopped-up

version of the older Stinson Junior. Bob Ayer, of GeeBee fame, had

come on board, specifically to get speed out of the Junior. The

cantilever gear and new fuselage shape were his ideas. The original

Reliant wing was the straight barn door of the Junior, but as the

design was refined through to the SR7, the planform was changed

to a birdlike shape and the thickness was made to taper out to the

struts and then back down out toward the tips, giving it a gull

shape-the Gullwing Stinson was created.

The crash survivability of a Reliant must be fantastic, judging

from its construction. The fuselage is a maze of steel tubing; the

wing spars are also a tubing truss. A thousand years from now some

archaeologist will dig up the fossilized remains of a Reliant and

think he's come upon the skeleton of a huge prehistoric bird.

There are conflicting theories and tales about the heat treating

of the steel truss works of the Reliant and the problems involved

in repairing certain parts. According to Fred Morris, in the civilian

SR series, only the gear is heat treated, while in the military

version, the V-77, the wing spars are heat treated.

To make a 3,800-pound, 42-foot, high-wing airplane perform takes

a lot of brute force; the force ahead of 39's firewall is a Lycoming

R-680-9 with 300 hp. Nothing carries the oldtime airplane sound

quite as well as a big radial at idle, and the Reliant's big round

engine certainly has that sound.

Fred and John take great care in keeping their monster machine well-groomed;

the engine is as clean looking as it is clean sounding. Because

of the sheer mass in the engine package, and the sculptured cowl,

one's eyes automatically track straight to the engine when the airplane

is first sighted. Its blunt, chromed nose and the many-cylindered

round engine are a good introduction to the rest of the airplane.

Going back down the fuselage, and stepping around the barrel-sized

pants, we climb aboard via a short stepladder. The ladder isn't

there to make boarding easier, it's there to make boarding possible.

The bottom edge of the door is nearly waist high—it would

take a second-story man to make it up without the ladder.

The door is thick and the opening it covers is large. The interior

resembles a well-appointed sitting room. The rear seat accommodates

three normal-sized men with a minimum of squashing and a maximum

of legroom.

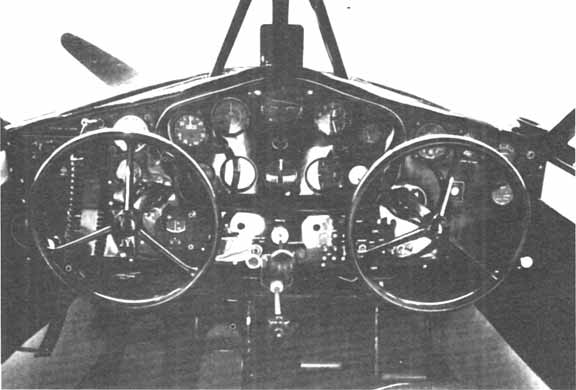

The impression of size heightens as you move forward and settle

down in the driver's seat, with the huge, polished, round wheel

in front of you.

The interiors of most restorations are disappointing, especially

in regard to details that go toward making a panel appear clean.

The inside of 39 is just as sharp as the outside; the panel is a

work of art. Its black enamel is spotless and every screw head,

every instrument, looks as if it has never been touched. The 1936

Ford-type panel grouping has flight and engine instruments completely

separated and mounted in recessed panels. The width and height of

the panel and the elbow room on the flight deck give one the impression

of being in an old airliner or perhaps on the bridge of a ship.

The Stinson is started with the prop in the low rpm position. The

big 300 Lyc took a bit of priming to coax to life, but it eventually

belched the oil it had collected in the lower cylinders, blew a

cloud of smoke, and settled into that low, throbbing rumble that

raises goose bumps.

Almost all taxiing and tight maneuvering on the ground is done with

brakes because the tailwheel is full swiveling with a lock for straight

ahead. Visibility is adequate, but just barely. There is a tremendous

blind spot to your right because the other side of the cockpit is

so far away that you have to S-turn tightly to see anything on your

right front quarter.

| |

|

| |

The Reliants, like all airplanes of

their day had an art deco flair to their panels that would

be a shame to smudge with stuff like modern radios and gyros.

|

|

It seemed as if every airplane in the country

picked this day to shoot touch-and-goes, and a Reliant is definitely

not the perfect vantage point for monitoring traffic. It has too

much airplane and not enough windshield.

Once traffic decided to let us go, we lined up and I reached under

the seat and pushed the tailwheel lock down to lock the wheel in

position. Fred had told me to pick the tail up at about 65 mph,

and to lift off at about 80.

I guess I'm used to an airplane that tells me when it's ready to

lift its tail, but there was absolutely no feeling in the controls

that said the tail was light and ready to go. Fred had to tell me

when to push, and then he had to help me because I wasn't being

forceful enough. The same is true of lifting off. When 80 mph comes

around on the dial, it takes a fairly good tug to get 39 off the

deck. Fred says she'll fly herself off, but it takes a lot less

runway if you forcefully pick it up.

In a cruise climb of 100 mph, we were getting better than 1,000

fpm with full tanks and three aboard. Some airplanes let you know

that you're climbing fast because they grunt and groan and show

how hard they're working. Not the Reliant. It climbs as effortlessly

and as smoothly as a hot-air balloon. The only indication of vertical

velocity is the rapidly vanishing ground.

All size, or bulk, disappeared as soon as we left the ground. At

cruise, it handles better than many so-called sports/ trainers.

I was really surprised how it responded to aileron and elevator.

It's no fighter, but it doesn't need two hands, which the tractorsize

wheel would indicate. The roll rate and control feel is similar

to a Cessna Cardinal, which is saying a lot considering that the

Reliant weighs about twice as much.

In cruise, N18439 takes quite a nose-down attitude to maintain level

flight. This attitude helps forward visibility immeasurably, but

the cabin roof and wing roof juts far enough forward that a lot

of sky is hidden. In the 1930s, traffic problems were not what they

are today, so visibility wasn't quite as important. Most airplanes

of this era have the same problem.

| |

|

| |

This sucker redefines the term

"big and beautiful." Its 300 hp R-680 Lycoming

appears almost small on its wonderfully sculptured nose.

The cantilever gear system uses inboard shock absorbers

a system that would show up again on the 108 series Stinsons.

|

Radials don't make much noise, and the cabin walls are so thick

that the noise level is about as low as it could be. Normal conversation

was easyone of the reasons the Reliant was so popular with the prewar

"in" crowd.

No pilot report is complete without a thorough investigation of

the stalls, even though few airplanes exhibit really hair-raising

characteristics. The Reliant is like the rest, even though it's

like full-stalling a house. The nose comes up, the airspeed goes

down, the airplane shakes, the nose drops, and forward pressure

and power remedy the situation. No sweat! Old-time bush pilots used

to be able to land Reliants in unbelievably tight corners, partially

because of its power and the absence of low-speed tricks. I later

proved that it takes a better pilot than me to park a Reliant in

a pea patch.

One thing about the Reliant that really surprised me is that with

all that wing, I expected it to float down, but its glide is more

of a trajectory than a glidepath. With zero power it bottoms out

at around -1,500 fpm, but with the power back and the vacuum-operated

flaps out, the VSI needle goes past 2,000 fpm like a shot. You wouldn't

have a whole lot of time to pick out a field when this one quits!

Keeping in mind that we were going to come to a screeching halt

when I brought the power back, I tip-toed into the pattern. I gave

myself plenty of room and moved the base leg out a bit so I could

make a power approach. Fred told me to make final a little high

and add flaps. I, naturally, overdid it.

In a normal airplane I would have floated right past the field,

but when those flaps came out and the nose pitched over, the runway

came right back up where it should have been. I held 85 mph most

of the way down final, slowing it to 80 mph over the fence. Fred

says he always wheels it on, so I thought I would, too. At least,

that's what I thought. As the speed fell and I tried to level off,

the control forces seemed to build up and were as heavy as they

had been on takeoff.

What was supposed to have been a thistledown landing turned out

to be the original Jersey bounce. I dribbled and skidded and waddled

down the runway on the mains. Fred says he puts it on main gear

first and lets the tail fall immediately, rather than trying to

hold it up. I didn't get a chance to test his technique. My arrival

was so sloppy I couldn't really tell whether or not it was easy

to land. My only conclusion is that it must be fairly forgiving,

all things considered, or I would have wrapped it up right there.

Fred said that he had no trouble transitioning and he really had

a transition. He owned a Smith Miniplane when he checked out in

the Reliant! ( Ed: I’ve since found that once used to the

airplane, it’ll squat onto the mains with little effort and

is actually fairly easy to land for its size)

At 130 mph and 15 gallons an hour, the Reliant is one of the classiest,

most luxurious ways of traveling. Each monthly issue of Trade-A-Plane

shows at least a couple Reliants for sale, averaging between $4,500

and $8,000 ( Ed: not any more!). You can move at the same

speed, carry more people, and have twice the fun of a Cherokee,

for little more than half the price. You do have to worry about

fabric and oil leaks, and a few parts are hard to find, but one

look at the early morning sun bouncing off that big cowling makes

it all worth it. Besides, you can always set up housekeeping in

it.

| |

|

| |

From this angle it's easy to see how

the Reliant got the nickname, "Gullwing." |

| Some

Random Personal Thoughts From 2006

If you ignore the miles per gallon, something like a Stinson

Reliant still makes sense as a piece of transportation. It's

considerably faster than a 172 (the honest ones, not those

in the advertisements), carries everything you own and raises

"class" to a higher artform. Obviously, it's not

a fly-and-forget airplane like a 172 and you're always tinkering

it. Plus, it demands you know how to fly, not drive. All of

this, of course, is not worth even considering as obstacles

when the class and overhwelming presence of the airplane is

considered. Besides, when was the last time you taxied up

to a gas pump in a 172 and had people crowding around it or

stretched out in the back seat to snooze? |

|

|