Change comes slowly in Kansas. From 5,000 feet, the agriculture patchwork has the same pattern it had in the early'30s, and only the occasional intrusion of a super-highway marks the difference between yesterday and tomorrow. The countryside is ageless, and not until you come close to a city does progress make its mark. As Wichita appears on the horizon and spills across the land in a wide, shallow puddle, the age of Aquarius, Skylab and JP-4 rises up and hits you in the face when the sweptback form of an F-105 thunders past. It is an olive-drab dart streaking across the sky toward McConnell AFB. There, alongside the scorched and rubber-marked runways, is the real indication of change. The gigantic Boeing plant stands with its back to the runways, dozens of jet-this and turbine-that huddled on the tarmac between. This is where the seed of change has buried itself in the Kansas clay.

In Wichita, change means aviation, and in the early '30s, aviation was still a fairly new word. The odor that wafted around the edges of town wasn't kerosene---it was butyrate and banana oil. The airplanes then were as simple as the rural setting that spawned them. We had yet to develop the horribly complex science of applied aeronautics, and words like chem milling and interference-fit didn't mean a thing to the workmen forcing dope deep into cotton weave. Because airplanes demanded nothing more than some tubing, a welder and a vague design, experimenting was easy, and the total number of a particular design produced didn't have to be astronomical to cover the cost of the primitive tooling and testing. It wasn't at all unusual to build only a few examples of a model, then turn around and start on an entirely new design. This was the technical environment that gave birth to the Stearman airplanes. No, not just the familiar PT-13/17 Kaydets that were a yellow blanket across the land during the World War II, but the earlier Stearmans as well. One of these was the Stearman Series Six, Cloudboy.

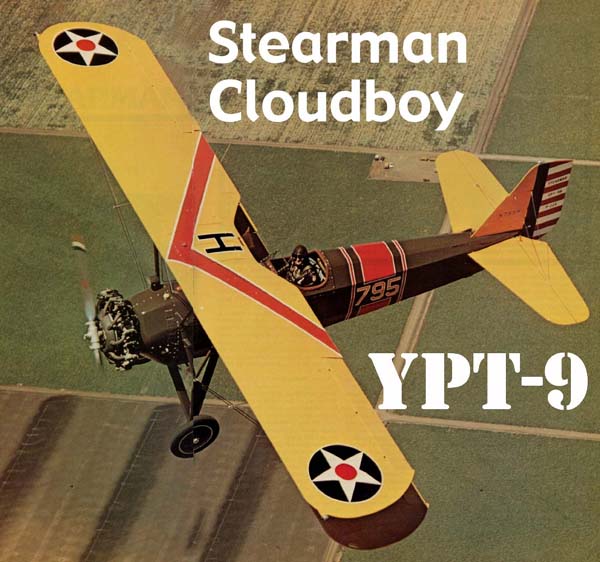

Only 10 Series Six biplanes were produced in 1930-'31. Four of these went to the fledgling Army Air Corps that was still looking for suitable replacements for their ancient Jennys and early PT series. The military had a delicious approach to selecting airplanes in those days: They would buy a half dozen each of several different airplanes, fly them and place production orders for the one they liked. The service test designation was Y, so the Series Six Stearmans became YPT-9s. The competition, incidentally, was the YPT-7, Mohawk Pinto, and the YPT-10, Verville Sport.

Originally, the YPT-9 was powered by the Wright J6-5 165-hp radial engine, the same as the civilian Series Sixes. Apparently the Army wanted a zippier trainer, because one of the first changes they had Stearman make was to modify the YPT-9s to take bigger engines including a 210-hp Kinner (YPT-9C) and the familiar R-680 215-hp Ly-coming (-9B). Two of the aircraft were re-engined with a 300-hp R-985 P&W and a 300-hp R-975 Wright. These 300-hp jobs were considered too hot for primary training, though, so they were redesignated basic trainers, YBT-9.

Airplanes have a way of disappearing over the years, and the YPT-9/Series Six is no exception. In 1953, only three were registered, then they all vanished, not to emerge again until the mid-'60s.

Even before they discovered two basket-case Cloudboys in a duster's hangar, Frank Luft and Elwood Leibfritz both of San Jose, California, knew they wanted one. They had seen one dusting crops and fell in love with the box-shaped fuselage and squared-off tail surfaces. A few years later, they heard of two airframes that were dying of neglect, so they formed an alliance with Ray Stephen and Darrel Hansen and went into the Cloudboy restoration business.

Since they all lived fairly close to one another, they decided to put the restoration on a production-line basis. They divided the work: The wings for both planes ended up in Frank Luft's garage, and the other parts were divvied up among the other four. One did fuselage work, Frank built eight new wings, and so forth, until parts for two complete airplanes had been remanufactured or built from scratch. They didn't merely want airworthy airplanes, they wanted award-winning representations of early-day military aviation. When they tightened the last flying wires and snapped the last Dzus, there was no doubt in anybody's mind that the past 5 1/2 years had been well spent. The two airplanes were absolutely diamond-like in their perfection.

The Luft and Leibfritz airplane had never been drafted into the Army. It was originally a 165-hp Series 6A, and served as a trainer for the Boeing School of Aeronautics at Oakland for many years. Around 1936, Boeing shortened the nose and hung a 215-hp Lycoming on it, making it a 6L. Even though it was never actually a soldier, tuft and company decided to dress it in period costume, hence the stars and bars. It was a wise choice, for it would be hard to imagine the airplane painted any other way.

When something is as unique and totally perfect as the Luft/ Leibfritz YPT-9, it's a toss-up as to which is more fun-flying it or watching it fly. As I was hanging out the open door of a saggy, rented Citabria taking pictures, I would frame the PT in the view finder so the top wing covered the front pit. Suddenly, I wasn't shooting a Stearman, it was a factory-fresh Curtiss F11C-2 or a Boeing P-12C (my favorite). The fuselage lines, the angular tail surfaces and the way the turtle deck stops abruptly at the cockpit says "Fighter, 1931." More than any biplane I've seen, the YPT-9 seems to exude the feeling of old-time military aviation associated with Sam Brown belts, riding jumpers and young James Cagney.

Walking around N795H and getting ready to fly, I mentally ticked off the many differences between the YPT-9 and the familiar PT-13/17. To begin with, it's a much smaller airplane, both in feel and in dimensions. Where the PT-17 Kaydet is rounded and stream-lined in a clumsy sort of way, the YPT-9 Cloudboy is flat and angular. The gear is the outrigger type that puts the shock absorber far out into the slipstream and definitely dates the airplane. The slab-sided fuselage and faceted turtle deck are laced together here and there with thongs to allow inspection of certain critical components. The Cloudboy's big low-profile tires contrast sharply with the PT-17's more modern balloon type.

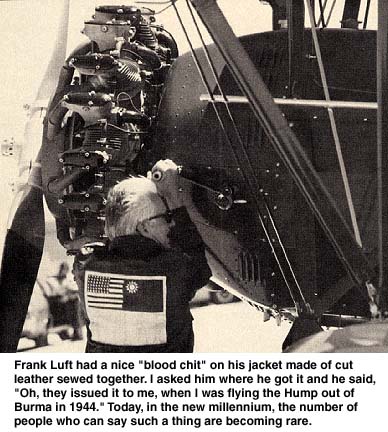

As we got ready to fly, Luft got into his flying jacket and walked forward to start cranking up the inertial starter. I lost count of the number of times he turned the crank to energize the starter's fly wheel, but it was around 50, with the last 10 merely picking the airplane up off the ground. I was strapped in the back pit and once the starter was cranked up, it ran long enough for Luft to leisurely walk back and show me how to start it. With mags on "left," I jerked the handle that engaged the starter, pushing a button marked, "booster" at the same time. The booster was a coil that fed extra spark into the system for starting.

As the starter engaged, it made a sound that can be described only as beautiful. The high-pitched whine of the fly wheel dropped sharply as the clutch engaged with the engine and the geared starter turned it over. One blade came by, then two. It belched a little blue smoke and coughed its way to life. Intertial starters may be a pain, but they're almost worth having just for that sound.

The ground angle is pretty steep, so I S-turned plenty to see around the nose. With the seat adjusted to the top, I was sticking halfway out of the enormous cockpit and could lean out into the slipstream and see almost straight ahead, but S-turning was easier. The steerable tailwheel was a little slow in reacting, but it didn't have to be any quicker because we weren't moving very fast.

Takeoff immediately reminded me that there was a time when "military" didn't mean "high wing-loading." I had the tail up and we were barely moving when the runway disappeared. We didn't take off; we sort of levitated at a ridiculously slow airspeed. Full throttle, the engine only cranked over 1750 rpm static and takeoff speed brought that up to only 2100 rpm. The engine was hardly turning, the airplane was standing nearly still, yet we were climbing at 600 fpm or better.

In level cruise, the big bipe showed 110 mph on the airspeed indicator, which means it would walk away from most of its grandkids, the PT-17s. It sits there, exuding a feeling of solidarity and the engine is barely audible over the wind as it rips around wires and struts. The tall stick controls the airplane easily, the four ailerons helping a lot, but a YPT-9 is far from being a round-wing Pitts. Of course, it's not supposed to be a superbird. It's a trainer and was designed to do everything the student told it to, at a speed that wouldn't let him fall behind. The control pressures are pleasing, but the response, especially in roll, is soft and slow.

Stalls in any configuration are non-existent. Straight ahead, tight banks, power-on, power-off, pulling did nothing but build up the rate of sink in a mush. Relax back pressure even a little and those gigantic wings reached out, filled with lift, and it was flying again.

Aside from training, the real forte of the Cloudboy (apparently bad promotional names aren't a new invention) was bouncing along several hundred feet over the trees on a late August afternoon. It would be a great airplane for frolicking with the seagulls on the way down the coast to Monterey or up to Vancouver. It's a born sightseer.

I turned final at 75 mph and started to reduce power. The wires and struts clutched the slipstream, and I found myself going down much faster than I wanted. It was almost as if the throttle was connected directly to the altimeter. To maintain speed, I had to keep the nose so far down I could see the run-way during the entire approach. As I leveled out at two or three feet, things suddenly got deathly quiet as the wind went out of the wires. It settled quickly, and I had to rush the stick back to get what I hoped was a three-point attitude. I made several landings, both wheelies and three-pointers, and I was amazed each time at how an airplane this big can slow to a near walk before actually touching down. Our ground-speed was in the 30- to 40-mph range, and the long-stroke oleos soaked up any bumps that were left. At that speed, with the wind on the nose, it would be pretty hard to get in trouble. The steerable tailwheel teamed up with the rudder to give all the control you could possibly want. A good healthy cross-wind might be an entirely different matter, though.

It's so sad that there are so few representatives of this period of aviation history still around. Antiquers are diligently building WW-I fighters, and airplanes of the 1920s aren't rare anymore. But the military birds of the later '20s and early 1930s have disappeared. Looking at the YPT-9s, one can't help but wonder where all the P-12s, F11Cs, P-6Es and others have gone. They were simple airplanes-a man with a complete machine shop could build one-but somehow the size of the project prevents anyone from attempting it.

I guess we'll have to settle for looking at the YPT-9s and daydreaming. If you squint your eyes and dream hard enough, the Cloudboys really do look like early P-12s. BD