STEARMAN-THE LEGEND LIVES ON!

Text and Photography by Budd Davisson, Air Progress Vintage Guide, 1989

STEARMAN-THE LEGEND LIVES ON!

Text and Photography by Budd Davisson, Air Progress Vintage Guide, 1989

Legends are often gossamer entities based upon hearsay or half-remembered acts

of long past heroism. Legends are composed of facts and non-facts that have

been polished and re-shaped by the erosion of the passing years and, because

the subjects of the legends are gone or are widely scattered, it's difficult

to separate fact from fiction.

Airplanes such as Mustangs, Thunderbolts, Messerschmitts live on and in the

never-never land of remembrance because there are so few of us who actually

have a chance to get close to the legend. So the majority must content themselves

with the few tidbits of information that come rolling down off Mt. Olympus.

|

|

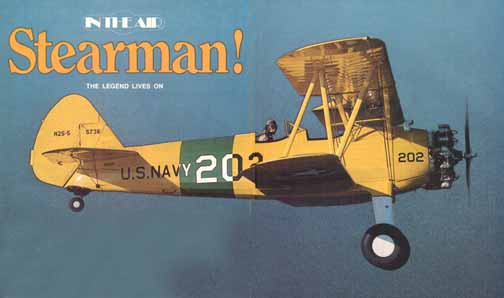

The Army PT-17's used the Continental 220 while

most Navy N2S's used the 225 hp Lycoming R-780. |

There are very few legends around to be tested and prodded each day, and fewer still manage to come through with their halo intact. One of these is the Stearman Kaydet. Known under a dozen different designations and flown by as many countries, the Kaydet has earned its spurs as a legend in three completely different life styles: as a military trainer it was a standout; as a crop-duster, it battled bugs for three decades; and, today, as a premier antique it still maintains the legend status.

The sacred crypt of the Stearman Legend is continually being opened and re-evaluated

in the hard light of present day. One reason the Stearman is continually being

poked and prodded is that there are so many of them around. Any fly-in of any

size is bound to have several restored or customized examples on the flight

line. Nearly half of the 8,585 built are still on the registry (it has often

been quoted that the number produced was 10,346 but that includes nearly 2,000

equivalent airplanes of spare parts). Also, just for the record, the Stearman

is not a Stearman. It's a Boeing. Prior to World War Two, Boeing Aircraft absorbed

the Stearman Airplane Company and continued to operate it as a separate facility.

Still, you never hear the big-boned biplane being referred to as a Boeing.

It should be understood that there were quite a large number of different airplanes

built under the Stearman umbrella, dating back to 1927. These airplanes included

a tremendous variety of open cockpit biplanes, multi-engine military bomber-trainers

and several variations of innovative and good looking civilian designs such

as the Stearman-Hammond Y-1S and the Stearman Aerial. A fascinating piece of

literature which traces all the Stearman products is the Stearman Guidebook,

published by Flying Enterprise Publications (3164 Whitehall, Dallas, Texas 75229).

If you flip through enough pages in this guide book you'll find the Stearman

that has become the object of so many aficionados' affections is officially

known as the Model 75, the final design in a long line of basically similar

military trainers.

Every time I hitch up my britches to climb up on the lower wing of a Stearman,

I am always impressed by its sheer size. The lower wing is nearly waist high

and, as you lower yourself into the cockpit, you can't help but notice how much

room there is available. There probably isn't a person alive that can't fit

into the rear pit of a Stearman. This eliminates any fatso's excuses. Obesity

no longer keeps them out of the cockpit.

|

|

Compared to any most other trainers of WWII, the

Stearman was huge. |

Of the other three most popular World War Two trainers, the SVA Stamp, the de Havilland Tiger Moth and the Bucker Jungmann, none come close to the Stearman in sheer size. At 1,936 lbs empty, the basic Stearman weighs as much as the Jungmann (836 lbs) and either one of the other two combined. Also, when you saddle up any of the other three and close the little cockpit doors, you are conscious of being, if not scrunched, then at least very well contained. This is certainly not the case with the Stearman, since you literally rattle around in the flight deck.

The Stearman is your basic man-size airplane and everything you see in the cockpit

is equally healthy. The big cast aluminum rudder pedals hang from a massive

structure, the control stick is bigger than the landing gear leg in a Jungmann

and everywhere you look are forgings and castings.

To fully appreciate the incredible strength built into a model 75 Stearman (PT-13,

17, 27, N2S, 1, 2, 3, etc.) you have to see one stripped naked. All of the fuselage

tubing is the size of gas pipe. The tail wheel shock strut and support assembly

is heavier than the main gear on many medium size light aircraft. The landing

gear is a marvel in rugged over design. The gear legs do not flex at all. They

are part of a rigid, one piece system that bolts to the bottom of the airplane.

The wheels are mounted in axle/strut assemblies that slide up and down in the

bottom end of the landing gear legs. If you feel an overwhelming urge to crash

an airplane, this is obviously the one to do it in, since the Kaydet will poke

a hole in anything you decide to hit. The average cost of the military PT-13/17

was between $9/10,000 and looking at the structure it is hard to see how Boeing

could to do it at that price, even in pre-inflation dollars.

Saddling up, the first move is to adjust the rudder pedals and pick one of the

eleven vertical seat positions that fit you. You can range anywhere from 5 ft

6 in to 7 ft and still find some combination that works. Fuel on, mixture rich,

mags on; the next step depends on the aircraft in which you're sitting. The

majority of today's Stearmans have normal electric starters so you just reach

over and punch a button. But a majority of the original PT-13/N2S trainers with

R-680 Lycomings (PT-17’s had 220 hp Continentals) had inertia starters.

Someone stood up by the left gear leg, cranked his brains out until the flywheel

on the inertia starter was screaming. He then jerked out an engagement lever

and the big Lyc coughed into life. Today, many find it simpler just to grab

a hold of the bottom prop blade and yank that big old radial into life.

|

|

On a good day you can count on 100 mph while going

cross country, but it sure is fun! |

I've always been impressed with the Stearman's ability to taxi with ease, considering that the aircraft has remained virtually unchanged since the Navy first placed its order in 1934 (the USAAC bought PT-13s in 1936). It has none of the pain-in-the-tail characteristics often associated with airplanes of the time. The tail wheel is steerable through 35 degrees, at which point it kicks out and goes full swivel and the big drum brakes are, assuming they are properly maintained, perfectly matched to the airplane's size and use. Granted, you may not see as well as you would like around all the windshield framing and sheet metal that's in front of you, but the aircraft responds beautifully to S turning for straight-ahead visibility.

I don't fly Stearmans as much as I would like to, so maybe I'm more conscious

than I should be of at least one peculiar sensation during takeoff. As the power

comes up, you can bring the tail up just about any time, but, in so doing, I

have always been extremely aware of the airplane's size and bulk. This feeling

runs head on into the fact that the Kaydet seems to get off the ground a long

time before it really should. Keeping the machine straight in the middle of

the runway is no problem at all, even in a crosswind, and the four big panels

were designed to get off the ground long before you can get yourself into serious

trouble.

Climb performance with an airplane that grosses out very nearly 3,000 lbs and

has only 220 horses up front is going to be leisurely. You don't have any choice.

Naturally, the 450 horse R-985 conversions change that story quite a bit and

600 horse airshow machines and sprayers are a different tune altogether. Those

with the R-1340 up front seem to hunker down at the end of a runway and leap

straight up.

As you come up to altitude in the Stearman, it's helpful if you mentally shift

gears. Try to remember why and when the airplane was built. When a Model 75

and its predecessors were brand new, front line equipment for the Army Air Corps

consisted of Boeing P-12s and P-26s while the Navy was still working with F4B-4s.

It was built to train an air force that was going to climb into cantankerous

little anachronistic bumblebees and go off to fight an enemy that didn't exist.

The Stearman soldiered on until, when it was finally cashiered out of the service,

the P-51 had been obsoleted by the whine of Lockheed's P-80. Other air forces

used it well into the period during which Stearman graduates would eventually

find themselves at the controls of Century Series jets. The Stearman is, and

was, a "trainer." In fact, it may just have been "the”

trainer.

|

|

The airplane was designed to be maintained by

a 19 year-old crew chief, so its systems are super simple. |

A casual glance through the Stearman's training manual shows just what type of pilot the Army expected to be sitting straddle of the rear stick. It has such profundities as ". . . avoid crosswinds." Or an even more prosaic "aileron controls are operated by control stick in either cockpit." You don't get much more basic than that.

One part of the manual I especially like is the admonishment on the cover that

says "this publication shall not be carried on combat missions or when

there is a reasonable risk of it falling into the hands of the enemy."

I guess it makes sense not to take any chances, but not too many Army pilots

went out to battle FW-190s in Stearmans. Besides, the manual on the Stearman

is as basic as the airplane, which means you could have Hitler on its mailing

list and still not give him any information that would tip the balance of victory.

Certainly one of the factors that makes the Stearman such a marvelous trainer

is its demand for absolute coordination at all times. The need for coordination

is both necessary and obvious. You sit well aft in the airplane and any slipping

and sliding can be seen and felt immediately. Also, the control movements are

large enough that you know you are actually moving your hand. It's not a question

of a gentle pressure this way or that way. You know the control stick has moved

left or right and that one foot has followed it in an effort to cancel out the

airplane's noticeable adverse yaw. If trainers still flew that way, we wouldn't

be cursed with the current generation of raglegs who think the only purpose

for their feet is to keep their socks separate and to activate the brakes on

landing.

In messing around doing aerobatics, I suppose I have stalled the Stearman just

about every way you can. Straight up, straight down, sideways, etc., I've always

found it to be a gentleman. If you force and yank real hard, yes, the stall

will break. But when it does break, it doesn't go anywhere. The Kaydet gives

you plenty of time to correct. In a normal stall series, the plane simply drops

the nose and mushes ahead until flying speed has been reached.

If you stall it and slide the ball about three widths off of one direction or

another, the airplane will break into one of the nicest spins of any airplane

around. Absolutely textbook in nature, it goes around at a moderate speed, almost

talking to you all the way around about what the handbook says concerning opposite

rudder and forward stick. In doing spins in the bird, I've always been conscious

of the naked feeling that such a big, wide open cockpit gives to those of us

more accustomed to tinier flight decks.

The roll rate is not exactly sparkling, but it is certainly adequate for the

intended purpose. I've always enjoyed doing aileron and barrel rolls in the

airplane but you must start nose high because to keep it positive you are going

to wind up fairly nose low. It's easy to see why all the airshow performers

have converted theirs to feature an extra set of ailerons in an effort to jack-up

the roll rate:

Anything that requires going up also requires a lot of going down. If I have

a complaint about the Stearman, that is it. You spend an awful lot of time going

downhill trading altitude for speed. In doing loops, you poke the nose down

to get a good number on the airspeed, pull the nose up and work over the top

of a loop in time to find that you have to spend another three or four minutes

climbing to regain your lost altitude. Again, this is something the 450 Stearman

doesn't have to worry about.

|

|

Every basic skill a pilot could possible want

was instilled by the time they spent in the Stearman. |

Certainly one of my more memorable moments in the Stearman

was being shown how to do an English bunt. The single most unnatural movement

that a pilot can make in an airplane is pushing the stick forward from level

flight and watching the nose curl under. It was a simple matter of working the

nose around until it felt like my intestines were going to extrude through my

eardrums, and then rolling out on the bottom as if it were an Immelmann in reverse.

This is one area where the Stearman's high drag certainly works favorably.When

you push the Kaydet over to an outside maneuver like that, the plane takes time

gaining speed and you have plenty of time to make the corner.

Speaking of gaining speed going downhill, there's a Stearman folk tale that tells of a couple of bored instructors at some place like Hondo, Texas, who are supposed to have climbed it up to 10 or 12,000 feet and pointed the nose straight down and let her rip to see how fast they would go. The placarded redlineis 186 mph and it's damned difficult to reach even that speed. Part of the Stearman Legend says those instructors had it up to nearly 300 mph with no damage. I don't doubt that the airplane would stand up under that kind of speed, but I doubt if you could climb high enough to make a downhill run long enough to get that kind of speed.

Several years ago at the Oshkosh Airshow, an aerobatic performance with a 220

Stearman really impressed me. The pilot showed what could be done with the minimal

amount of power and absolutely zero outside capability. Most of the crowd, already

glassy-eyed from watching various Pitts, Lasers and 450 Stearmans didn't appreciate

what they were watching. Those of us who have tried to do the same thing in

a stock Stearman appreciated the hell out of it. (Ed Note: That would be John

Mohr, the airshow pilots’ airshow pilot).

If there are Stearman horror stories, they almost always concern landings. In

actuality the Stearman's landings are anything but horror stories, but you do

have to keep in mind it has several unusual characteristics. Sixty to 65 mph

is about the minimum approach speed, although it doesn't seem to make any difference

since the minute you bring the nose up, all those wings and wires burn off speed

in a heck of a hurry. If you're high on final, just put the stick on one corner

and the rudder on another and the Stearman comes down in one of the nicest,

most civilized slips known to mankind.

Everytime I come into land a Stearman, I hear myself saying, "long gear,

long gear, long gear . . ooops!" You sit so high off the ground in this

airplane that nine times out of ten my first landing is actually two, or maybe

even three, because I hit the main gear before I am actually ready and get a

little hop out of it. Many pilots chicken out and land it on the main gear in

a wheel landing. There's no real reason for that procedure. A good three-point

puts you on the ground so slowly that, as long as you hit straight and keep

going straight, you'll have no problem. However, let the Kaydet start swerving

one direction or another and you'll find that high center of gravity works with

the narrow landing gear, making it easy to catch a wing tip

.

I've been told by old military instructors that they taught their students not

to try to pick up the down wing in a groundloop with opposite stick because,

in so doing, the outside aileron would be down and would get crunched in the

groundloop. The crew chiefs preferred them to go ahead and drag the wing tip

but save the aileron, since the wing tips were nearly indestructable. Of course

none of this is a problem on grass where the airplane is a real pussy cat. On

pavement all you have to remember is what your feet are for and keep looking

at both sides of the runway to make sure you are actually straight before touch

down.

I'll have to admit to being disappointed with my first flight in a Stearman

because I was imbued with "The Legend." I had been watching too many

folks like the Cole brothers and Bill Adams with their big engine four aileron

airshow birds. During my first flight I thought I had my hands on a real turkey.

As I've gotten older, I've come to judge the Stearman for what it is: A classic

example of the way to build a trainer that will transform students into pilots

and do so day after day with a minimum of upkeep and repair.

Although the days are long gone when you could pick up a surplus Stearman for,

$400 or $500, in terms of pure practical antique aviating the Stearman probably

represents the pinnacle in the crossover between anachronisms and practical

flying. The parts are plentiful but seldom needed. The appearance is antique,

but the handling and approach is modern. Yes, it is deserving of the legendary

status. What's more, we will be several dozen generations of pilots down the

line before Stearmans even approach becoming extinct. When we are busy colonizing

outer space, we will probably be relaxing by restoring Stearmans.

SPECIFICATIONS MODEL 75

Span .................................. 32 ft 2 in

Length .................................. 24 ft 9 in

Height .................................... 9 ft 8 in

Wing area .............................. 297.4 sq in

Empty weight ............................ 1,931 Ibs

Loaded weight ............................ 2,635 Ibs

Maximum speed .......................... 124 mph

Cruise speed .............................. 106 mph

Initial climb .......................... 840 ft per min

Range .................................. 505 miles

Engine ................... Continental R-670-5 220 hp, Lycoming R-680, 225 hp

For

lots more pilot reports like this one go to PILOT

REPORTS