When this was written, Hale Wallace was still very much alive and

contributing mightly to the world of homebuilding in general and the

world of the biplane in particular. He taught me a lot of things during

our three decade friendship but the one I'd like to pass on that I took

the most to heart has nothing to do with airplanes. Hale died simply

because he got lazy about going to the doctor and hadn't had a PSA test

for at least five years. None of us should do that. It would have been

a simple operation, had he just gone to the doctor once a year. But

he didn't and all of his friends paid the price of his passing. If you

take nothing else from this article, take with you the knowledge that

simple annual check ups can save your life and, in so doing, prevent

an enormous amount of pain to your friends and family. Sermon over.

My mind was in biplane mode: Head back, vision foreshortened and out

of focus so my eyes were staring straight ahead, my peripheral vision

watching both sides of the runway at the same time. I was seeing everything

but focusing on nothing. My left hand started forward and what had been

a steady rumble from under the cowl which rocked the Skybolt even as

it sat on the end of the grass runway became an enraged beast. The airplane

lunged forward, the wall of noise rolled back over me and I had the

weirdest feeling I had just passed beneath a lion's fangs and was rocketing

out the back side of his maw.

325 horses were reducing the hangars and edges of the runway at Shiftlet

Field, Marion, North Carolina to meaningless blurs. They were of no

consequence. Only the shallow circle which encompassed the airplane's

nose and the edges of the runway counted.

| |

|

| |

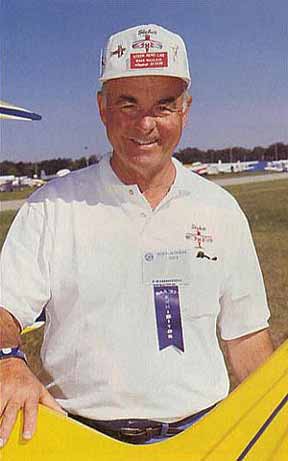

The master himself: the late Hale Wallace.

The Skybolt is now kept alive by Steen Aerolab www.steenaerolab.com.

|

I kept waiting for the acceleration to let up. For the speed to become

constant. As the tail came up and more of the runway came into view,

the seat kept insisting itself upon my backside. The runway kept flashing

past and I approximated a slightly tail down attitude. Taking a second

breath hadn't yet occurred to me when the airplane skipped once and

clawed its way into the air.

I glanced at the airspeed. It was already racing through 110 mph so

I pulled the nose up. Then more. I stopped at what looked like a suitably

ridiculous angle that held the 110 mph. The VSI was lounging around

2400 fpm.

So this is what happens when the boss builds himself an airplane. This

is what a Skybolt feels like when Hale Wallace, operator of Steen Aero

Labs (704-652-7382) home of the Skybolt builds one for himself.

Hale spends most of his waking hours working on biplanes and components

for them. He not only is the exclusive distributor for Brunton flying

wires (which makes him the sole source for ALL flying wires since MacWhyte

closed down) but he also owns the rights and sells plans for the S-1C

series of Pitts Specials, including the Super Stinker wing update for

the four-cylinder airplanes. He has the same rights and plans for the

Knight Twister (he'll have one of them at Oshkosh next year, and is

it ever cute!). On top of that, he is the exclusive US distributor for

the Hoffman series of fixed and constant speed propellers.

Most of what Steen Aero Lab does, however, has to do with Skybolts:

Plans, finished components up to wings and fuselages, Hale Wallace is

Mr. Skybolt, world wide.

So, when Mr. Skybolt decides to build himself an airplane, what makes

it different than the rest?

"Basically, this airplane is built right to the plans," says

Wallace. "We did, however spend a lot of time at reducing weight

ever where we could. For instance, for the firewall, we used .020"

titanium, which not only saved around six pounds, but titanium is much

easier to work than stainless steel."

Titanium is use liberally through out the airplane and each use is documented

by engineering back-up.

"All of the heavy bolts, like attach bolts, are titanium. So are

the drag/anti-drag wires and all the push-pull tubes. We used it every

where it made sense and the numbers looked okay," he says.

"We used the Hague locking tailwheel for a number of reasons, weight

being one of them," Hale points out. "It's three or four pounds

lighter. It also, however, lets us get the tail down another couple

inches and we need the prop clearance."

Although the wings are still basic Skybolt, there too Wallace has put

his experience to work.

"The wing spars are routed, using a hard tooling template we've

developed. That alone saves about 15 pounds an airplane depending on

wood density. In total, we've knocked about 30-35 pounds out of the

wings alone," he says.

In building the wings, he also put his experience to work to get the

most roll performance possible out of the basic Skybolt wing design.

He has done Skybolt wings using the Pitts Super Stinker aileron technology

(symmetrical ailerons with special nose profile), but decided to stay

with the normal ailerons on this one.

Wallace says, "Good roll rate and response is due as much to the

fit of the ailerons as their design. What we do is finish the wing up

through the first coat of silver while working at getting all of our

aileron gaps down to less than a quarter of an inch. Then we close up

as much of that gap as possible with balsa filler strips and put the

finish tapes over the balsa. By waiting to finish the aileron wells

until after the fabric is fairly tight, we eliminate the problems of

distorting the aileron wells in the final covering steps."

Wallace is especially proud of the canopy on the airplane.

| |

|

| |

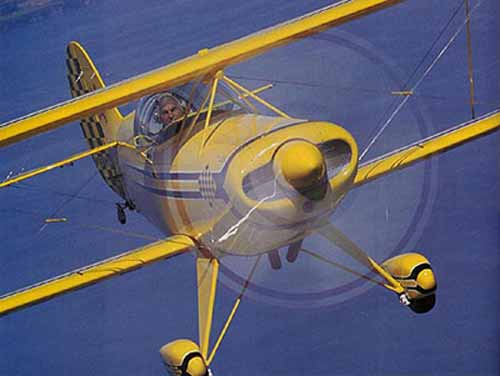

Hale's airplanes always abound in ridiculously

tidy details that make the rest of us feel like butchers. |

"Anyone who has ever done a canopy installation on an airplane

swears they'll never do another, " Wallace laughs. "This canopy

solves the problem of making everything fit because you build it on

the airplane. I saw a photo of a similar type of canopy on a Skybolt

built by Francois Mounier-Poulat in France 20 years ago. Francois ,

by the way, is now my sales representative over there. We took the concept

and refined it. The entire assembly only weights about 12 pounds, which,

if you subtract the weight of the open cockpit windshields only adds

about 10 pounds to the airplane."

The canopy bubble is glassed into a form-fitting apron and attached

to the airplane by a trapezoidal steel tube frame which swings from

behind the pilot, when open, and lays on the longerons, when closed.

A spreader bar bridging over the instrument panel is made of cross-grain

balsa for light weight and easy bending and is captured in glass cloth

and epoxy for rigidity. The bar is only there for a handhold, according

to Wallace. The bubble pivots up and back, completely opening up both

pits for exit and entry.

Another aspect of Wallace's bullet is the engine. Hale went to Monte

Barrett, who is best known as one of the premier builder of aerobatic

engines, but is now accepting orders for more "normal" engines.

Normal in this case included taking a lowly 235 hp 0-540 Lycoming and

swapping parts around until it was putting out close to 325 hp on the

dyno. This includes one of Barrett's cold-air induction units.

As the US Hoffman importer, it is no surprise one of their three-blade,

composite props caps off the propulsion department on the Wallace Skybolt.

The airplane is finished in Randolph dope

| |

|

| |

I wish this was a bigger photo but it's

the biggest, I have. Sorry. |

"For health reasons, I try to stay away from any of the polyurethanes,"

Wallace explains.

"Also, I always use Razorback on the fuselage because it is nearly

bullet proof and has a neat appearance on the inside. I'd prefer to

use cotton on the wings, but you can't find good cotton, so I use dacron

like everybody else."

What ever he uses, the airplane looks terrific!

As I climbed on board Wallace's airplane, I'll have to admit I first

thought the canopy arrangement to be a little fragile looking and probably

hard to manage. I was wrong on both scores. All I had to do was reach

behind my head and urge it forward until the canopy pivoted down and

I held it by the spreader bar. There couldn't have been more then a

pound or two in my hand. It was necessary to pivot the canopy so the

nose was pointed down hill. From then on, it was a simple matter of

dropping it into place and locking the two canopy latches. To jettison

it, all I had to do was pull a pit-pin on either side of the cockpit.

Hale had warned me to keep the stick back while the engine was running

because letting the stick forward could raise the tail with the smallest

application of power. As I moved out towards the runway, I could see

what he was talking bout. There was absolutely no doubt that there was

a truck load of horsepower under the hood.

| |

|

| |

The Monte Barrett massaged 0-540 with

its high compression pistons and cold air induction pumped out

325 hp on the dyno and, when you dropped the hammer, you felt

every one of those horse. Very cool! |

I'm not a fan of locking tailwheels on little airplanes, but this one

worked quite well. Wallace had used the throttle assembly off a lawnmower

as the engage mechanism which was located under my left hip. With the

tailwheel locked, it drew a rail-straight line. With it unlocked, the

airplane was perfectly willing to go someplace else and took some brake

to stay on top of it.

That first takeoff was exhilarating, to say the least. It was right

up there with any of the rocket-powered aerobatic specials. Just keeping

the speed down to an acceptable level during the climb was an interesting

chore. Later I tried climbing at best rate, which is down around 90

mph, and the angle had to be approaching 45 degrees. It was ridiculous

and fun at the same time. The rate of climb was well over 3,000 fpm.

In a couple of minutes after that first takeoff, I was at 5,000 feet

and let the nose down and the speed build. And build. Showing 2350 square,

it stabilized at about 165 mph indicated which at that altitude and

temperature was well over 170 mph TAS. This has to be the fastest Skybolt

in history! Hale said his two way average going to Tulsa for the biplane

bash was 176 mph at less than 13 gph. Now, that's hauling for a big

biplane!

Incidentally, I tried running at reduced power settings just to see

how much of the speed was due to brute horsepower and how much was airframe

related. Backing the power off to what I guessed to be more normal power,

only brought the airplane down to about 150 indicated, so it was still

quite fast. This is undoubtedly because the airplane was probably the

straightest Skybolt ever built.

This airplane was an easy 35 mph faster than any Skybolt I'd ever sat

in and that extra speed was noticeable in a number of ways. At normal

Skybolt speeds, the aileron pressures were lighter than most I'd flown,

about on a par with a Pitts S-2A with fairly quick response. Don't forget,

a Skybolt is much larger than a Pitts, so shouldn't be as nimble, but

it's closer than you'd think. As the speed went up, the pressures built

slightly until they were about the same as the S-2B, but the roll rate

increased at the same time.

| |

|

| |

Just your basic, snarling beast of a

biplane, that has the manners of a pussy cat. This is a hard airplane

not to love. |

The canopy seemed to let the entire world into the bigger than average

cockpit. That's always been one of the Skybolt's strong points: It's

cockpit size and shape makes it really comfortable. You're sitting there,

legs spread wide, laying back at just enough angle for it to be easy

on beat up backs like mine, while the incredibly smooth Lycoming up

front is helping you stack up the miles. No homebuilt biplane is Cessna-stable

but the Skybolt comes close. Combine that with a good GPS and the urge

to go someplace usually can't, and shouldn't, be resisted.

The airplane had so much more straight level speed than most Skybolts

that dropping the nose for any kind of overhead maneuver was overkill.

It was perfectly happy to loop out of level flight and hold its altitude.

In fact, if you weren't careful, you'd gain altitude. It would do a

half-vertical roll from max level with a hammerhead turnaround and another

half roll on the way down without breathing hard. Dropping the nose

just a tad gave 200 mph and it would do anything from that speed.

The speed gave the airplane a ballistic feeling that I generally assume

to be coupled with a much higher wing loading. This lead to a mis-perception

on my part. It felt like a heavy airplane, so I flew approach like it

was a heavy airplane. Here again, I was wrong. Let the record show that

90 mph over the fence is entirely too fast for the airplane. After a

lovely, easy to control, slipping approach, I blew it and floated half

the length of the runway before it decided to land.

Power up, let's try that again.

This time it was 85 mph. Skybolts are all wonderful slipping airplanes

which does away with any blindness factor until just about ready to

touch down. Even then, the visibility is much better than most taildraggers.

Let the record show that 85 mph is still too fast. Too much float. Too

much runway behind me on touch down.

It became obvious the diet Wallace put this airplane on had paid off

and it was going to take a bunch more approaches before I had it figured

out. What I didn't have to figure out, however, was the ground roll.

Once it touched down, I'm not certain I moved my feet at all. Most Skybolts

are pussy cats, but this one was nose-wheel simple. Maybe there's something

to this locking tailwheel thing after all.

Ignoring the massive amount of power, the most important factor one

should bring away from studying Hale Wallace's personal Skybolt is that

attention to detail pays off. There was nothing about the airplane that

was overtly fancy. No chrome. No super-stitched upholstery. No fancy

anything. However, there was absolutely nothing out of line. No gaps

that were uneven. Everything was simply "right." It all fit

and lined up. That meant the airplane flew the same way. It was absolutely

one of the most die-straight airplanes I've ever sat in and that alone

made it a pleasure to fly. Toss in 325 of Barrett's famous ponies and

what's not to like?

When the boss builds an airplane for himself, he builds it the way he

wishes everybody would and it shows.