|

What follows is a pilot

report on the first Skybolt the late Hale Wallace ever built. The year

was 1971. Years later Hale was to purchase the design rights and set up

his own Steen Aerolab supplying kits and components. Hale was one of the

most fantastic craftsmen I have ever known. He made “perfection”

look sloppy. He was also one of my good friends and I hated it when cancer

took him. However, even in dying, he set an example for everyone to follow.

He faced his own death with a humor and dignity I can’t expect to

duplicate. He had a little of the junkyard dog in him, a little bulldog

and a whole lot of toy terrier, as he just loved having fun with airplanes.

He was one of a kind.

My mind was yelling at me, "Aaahy, Dummy! That

was the horizon that just went by, Do something!" So, I hammered

the stick forward and punched opposite rudder, bringing the snap roll

to an unbelievably sloppy halt.

"Tilt!" my brain chided again and I obediently brought the wings

back to a semblance of level flight. I had been suckered! The Skybolt

had played around on the corners of my consciousness at the airshows for

years and I had always ignored it, passing it off as a chubby, backyard

knock-off on an S-2 Pitts. But, as I yanked and pushed my way around the

sky in Hale Wallace's Skybolt, I had the subliminal feeling that the airplane

was getting back at me and ultimately would have the last laugh.

| |

|

| |

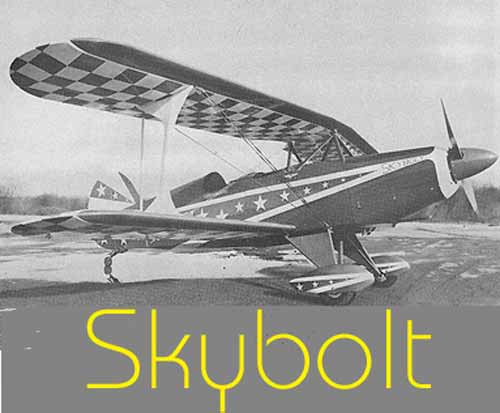

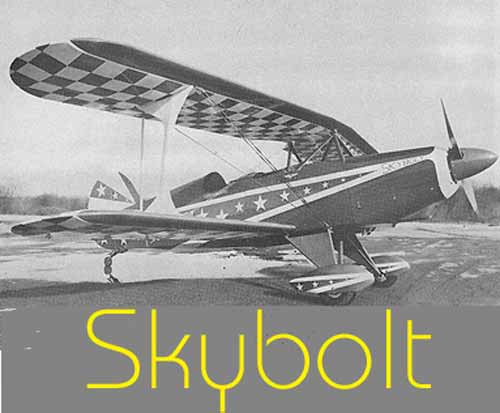

The lines of the Skybolt are vaguely Pitts-like

in that the top wing is a swept one-piece unit, while the bottom

wings are straight. It should be noted that Curtis Pitts designed

a three-piece top wing for the current Steen Aerolab who offers

it in their on-line catalog (www.steenaerolab.com).

It is a much easier to build wing than the original. |

I had stuffed Wallace in the front pit of his airplane

so I had a two place machine that was doing what it was supposed to be

doing—carrying two people, some fuel and flip-flopping around the

sky. Wallace, of Binghamton, New York, had not only loaned me his Skybolt,

but also volunteered to play ballast bag while I poked into the various

corners of the Skybolt's soul. It was, I surmised, the worse possible

situation to place the airplane in for an aerobatic evaluation. With the

extra weight it wouldn't be performing at its best, so I could assume

that whatever I found out about it would only be improved when flying

solo. If that's the case, then as a single-place airplane the Skybolt

must be a real brain breaker because even with two of us aboard it was

no slouch.

The Skybolt bears more than a casual resemblance to a two-hole Pitts.

It's a bunch bigger, 24 versus 20-foot span, but weighs about the same,

1100 pounds empty. Wallace uses a IO-360 solid shaft 180 Lycoming and

a fixed pitched prop and weighs in at 1150 pounds, exactly what my 200

hp S-2 Pitts does with a constant speed. But, remember, the Skybolt is

a sizable amount bigger. The airplane has a "feeling" of being

bigger when you're walking around it, but its flat ground attitude tends

to hide some of its size. I think I was most impressed by its size when

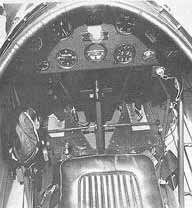

I tossed my butt up over the gunwhales and settled into the seat. The

flight deck is so large that it makes my Pitts seem like a chrome-moly

straightjacket (which it is) by comparison. No problem getting my pointy-toed

Texas wedgies past the seat to -the rudder pedals in a Skybolt.

The gestation of the Skybolt is a well known and, at this point, often

told story. LaMar Steen, school teacher, wanted an aerobatic airplane.

So he designed one. Students at Manual High in Denver built it. He flew

it, liked it. Had the structure analyzed by engineers. Others liked it.

More built.

That's where it came from, but, as I flipped the master on and wobbled

up some fuel pressure, I wanted to find out where it is right now. I wanted

to know what kind of bird it is in the air, not on the drawing board.

So, keeping the mixture lean, I pushed the starter switch, and, as it

began to light off the residual fuel in its intakes, I pushed the mixture

forward and settled back to follow the Lycoming wherever it wanted to

take me.

As I taxied out, making gentle "S" turns to see around the ridiculous

snout all biplanes seem born with, I worked the controls, trying to get

a feel of what moved what. I wished that I could have done the same thing

on a number of other Skybolts because I can't believe they all feel as

good as Wallace's. Slick is the only word to describe it. The only friction

in the entire airplane was between my tusche and the seat because the

throttle, stick, rudders, everything, felt like they were stuck in butter,

with virtually nothing touching them. That's probably a credit to Hale

Wallace's meticulous building techniques rather than the basic design,

but it's hard to tell without checking several other airplanes. (Ed note:

In later years I found that to be the case because the ailerons on Skybolts

vary considerably according to the builder.)

| |

|

| |

There is also a different landing gear

for the Skybolt now available that is a single leg per side, ala

Marquart Charger, with internal shock system. |

You sit low in a Skybolt. Or at least I do. It's traditional

biplane all the way, making the pilot look like a midget in a manhole.

I've always felt I looked like the caricature "Kilroy's Been Here,"

with my eyes and nose the only thing higher than the cockpit combing.

We were working off Sussex International's runways in New Jersey and even

with their adequate width, you don't see much pavement from the back of

a Skybolt. So, as I picked my way through the puddles of a traditional

messy East Coast spring, I carefully sized up the runway that was visible

and decided to keep the sides right where they were during the takeoff

and landing rolls.

We had a fairly healthy crosswind so I was cautious with everything on

that first takeoff. I fed the coal to the Lycoming slowly at first, letting

us pick up speed at about the same rate my brain was functioning. No reason

to scare the hell out of myself by dropping the hammer too hard. The Skybolt,

even with only 180 hp did its best to play fighter, and tore down the

painted stripe as if it had someplace to go in a hurry. I hoisted the

tail just a little and sat there, tail low and peeking at both sides of

the runway at once, while we raced up to a speed where airplane thought

it'd like to go flying.

At no time, not even in the crosswind, did I have to do a tap dance on

the rudders. It took a little pressure one way or the other, but for the

most part the airplane shot straight ahead with no tendency to ricochet

off runway lights on either side. It seemed to have a surprising amount

of directional stability.

For some reason or other I wasn't really aware of rocketing down the runway

with the noise and wind threatening to yank my head off, my eyes clicking

back and forth from side to side and all the other excitement that usually

comes with taking off in a Pitts or something similar. The headsets kept

out most of the racket, but otherwise, everything happened at a very easily

handled, albeit sometimes fast, speed. When the airplane lifted off at

about 65 IAS, it had no tendency to sag, rock, rumba or otherwise keep

you busy. I did notice, with a certain amount of delight, that I was fighting

the gusts with four of the smoothest, lightest ailerons I've had the fortune

to run around with. They were much, much lighter than I had anticipated.

The Pitt's are a fair amount heavier and a Starduster's seem set in concrete

by contrast. (Ed note: this is definitely not the case with all Skybolts)

| |

|

| |

Steen Aerolab has been experimenting with

an oil-damped, spring-oleo arrangement on the Skybolt, but it may

or may not be available to the public yet. |

At 85-90 mph climb speed, the VSI was showing about 1000

fpm which pretty well checked with what Mickey's sweep second hand was

telling me. At that rate, and considering the cool temperature, the Pitts

would out climb it easily. However, this is also where the constant speed

prop and extra 20 horses would make itself known. I forgot to ask Hale

what the pitch was on his prop, but judging from how it reacted in later

akro work, I'd guess he had a fairly coarse pitched set of blades up front.

At altitude I quickly reefed it around in a series of 90-degree turns

looking for traffic. Satisfied there weren't any Wichita sheet metal surprises

around, I reached into a corner with the stick and watched the Skybolt

turn Jersey upside down at least once, or was it twice? The silky ailerons

make any kind of roll a super sexy, kinetic affair. But that was to be

expected. Out of the roll I pulled around into the first quarter of an

inside rolling 360 and as I pushed it around for the negative portion

of the turn, got my first hint at a problem area.

Then, I pulled the nose up, hesitated and rolled over on my back, pulling

the nose through into a split-S, gaining speed for a couple of loops,

some rolls on a forty-five degree up line and a few things neither one

of us could identify. I can name what they were supposed to be, but there's

no reason to embarrass myself.

The first thing I noticed after cavorting for a while was that the Skybolt

doesn't accelerate downhill nearly as fast as the Pitts, nor does it fly

away from a stalled or nearly stalled situation as well. This would be

expected for a bigger airplane with less horsepower. I found it difficult

sometimes to get the entry speed I wanted fast enough because I had to

keep the throttle well back to keep from overspeeding the engine. That's

where the constant-speed prop is a neat piece of hardware to have on board.

| |

|

| |

The Skybolt is built for bigger butts because

Lamar Steen was, himself, not likely to fit into a Pitts. |

At one point I was diving and, as I went through 140

mph, I figured, "What the Hell, why not?" So, I whipped it over

inverted and pushed for all I was worth. I heard things starting to pop

in my shoulder and that was the second hint that the elevator pressures

when outside were something to be reckoned with. The airplane arced gracefully

upwards in an outside push-up, but believe me, spectators couldn't appreciate

the amount of muscle (of which I'm in short supply) it took to push it

around.

As we leveled out and stuffed our innards back into their proper positions,

Hale commented through the intercom that he had never pushed the airplane

outside like that before. I was entirely satisfied with the way the airplane

handled, so I naturally had to take advantage of the situation by offering

to take his aerobatic virginity for him. He half turned his head to give

me a dirty look, so, I explained that I believed firmly in Frank Price's

famous saying "If you ain't been outside, you ain't been nowhere."

He smiled (grimly) and nodded his head.

It's always a kick to take a guy around in his first outside loop from

the top, especially in his own airplane. So, I throttled back and waited

until the speed dipped towards 70 mph. Checking the wing tips to be sure

I was level, I began the gentle push followed by rapidly increasing control

movements that always occur in that downhill race for the bottom. I monitored

the airspeed carefully and played the G's to give me 160 mph on the bottom.

The airplane had a very, very nice acceleration rate that allowed me plenty

of time to level the wings as we were tucking the nose under. It was an

absolutely no sweat operation and as we streaked under the bottom, both

of us being cut into small sections by the various straps holding us in,

I was able to open up the arc a little and play the airplane up to the

top in what felt like a reasonably round loop. Of course, anybody watching

would have thought we were doing an outside egg or inverted pear or something,

but it felt good and only took 3 negative G's.

I had cranked in full down trim before pushing over into the outside loop

but even so the stick pressures fought me all the way around. I would

have preferred to see minus 3.5 or so on the G meter when we surfaced,

but as it was the stick made me feel as though we were going to get a

solid minus six. Apparently this is a common gripe because Steen is reportedly

changing the plans to include servoed trim tabs on the elevators as well

as a quick acting trim system a la Pitts S-2.

Somewhere along the line, I was watching the speed work its way back through

115 mph when I yanked the stick back into the right corner, stomping rudder

at the same time. Wham! The aforementioned snap roll suddenly got my undivided

attention. I guess I've snapped as many airplanes as most folks but it's

seldom that I get much of a surprise. Even so, the Steen did hand me a

surprise. Without doing some measuring it's dangerous to say how fast

an airplane is actually going around, but I know for a fact that the Skybolt

snaps faster than a Pitts S-2 and darned near as fast as a single-hole

Pitts. Even better than that, it stops where you, want it to, but you'd

better decide well in advance where you want to end up.

Unfortunately, the combination of its size and fixed high prop won't let

it fly away from a snap as well as I'd like. It does far better than any

other two-place homebuilt I've flown (I haven't had a chance at the two-place

Acroduster). Interestingly enough, the airplane snaps very well, although

slower, to the left, something you just can't get a two-hole Pitts to

do.

It spins extremely well and both the going-in and the coming-out are clean

and crisp because of the fat rudder and the big elevators. I wasn't exactly

stopping it on a dime, but with a little practice I would have figured

it out. It doesn't spin any faster than most airplanes of its type, none

of which is appreciably faster spinning than Cessna 150 when it's really

wrapped up.

When I first laid it over on its back, I was a little disappointed, because

it wants a bit more forward stick/trim than a Pitts, but a lot less than

a Starduster Two (which isn't really a fair comparison). Also, even a

bunch of forward trim won't take all the stick pressure off, although

I'm not sure I had the trim full against the stop. A Pitts will motor

along upside down all day hands off with only a little forward trim. Don't,

however, construe this to mean that the Steen was running around nose

high when inverted. The actual flight attitude seemed about the same as

a Pitts, which is about as flat as airplanes ever fly with the pilot pointed

the wrong way. Controlability and pitch stability when inverted was really

excellent. There was no tendency to have to fight to maintain a given

nose attitude.

As we let down towards the airport I once again reminded myself that somebody

somewhere has to come up with a biplane that you can see out of. To be

safe in the Skybolt (or a Pitts or a Starduster, etc.) you have to jink

the nose back and forth to see anything smaller than an L-1011 that's

in front of you. It is quite possible to design fuselages for bipes that

let you see, although the Acroduster One is the only airplane I can think

of right now that is so designed. Threading your way through the fog of

airplanes that surround most airports these days is no fun in an airplane

with the visibility of a timid turtle.

80-85 mph was the right number on final and I had to work a little to

keep the IAS needle anywhere close because of the bumps we were punching

through. A little wing down and some opposite rudder kept us lined up

and I had to kill the power completely to get down where I wanted. In

the same situation a Pitts or Starduster would have fallen out of the

sky much faster.

Closer, closer until I could see the edges of the runway where I wanted

them and I began a flair to skate gently across the invisible surface

of ground effect. Feeling for the ground wasn't really necessary because

the airplane seemed to naturally settle into the right attitude. All I

had to do was hold it as it kissed the runway with all three. I was all

eyes and nerve ends waiting for the airplane to demonstrate any bad manners

it had on the runway but it appeared to have none. Its gear seemed to

be just soft enough (the result of a fortunate choice of bungee cords)

to absorb the landing shock without being so soft that it waddled or so

hard that you skipped along rather than rolling.

A little rudder one way or the other kept things reasonably close to straight

until we braked to a halt. The rollout had been disappointingly uneventful

considering the wind and the reputation little biplanes have. In the same

situation, a Pitts S-2 or Starduster would have me doing more of a rudder

bar tango to stay on the centerline.

Does Hale Wallace like Skybolts? He must because he's building another

one, this one with a (are you ready for this?) IO-540 Lycoming with 260

fire breathin' horses. That will get the power-to-weight ratio down awfully

close to 6 lbs./hp, which is darned close to a single-hole Pitts' ratio.

What had been a spirited airplane is going to become a flaming tiger!

The Steen Skybolt will never be able to match maneuvers with a single-hole

Pitts, or a Stephens Akro. But, it's not fair to expect it to. The Steen

is a two-place airplane whose role in life is to offer an upside down

view of the world that can be shared with a friend. It would probably

do fairly well in Akro competition up through intermediate, but it will

never win. That is the domain of the single place birds. However, there

is something a one-hole machine can never give its owner—the satisfaction

of introducing someone else to the world of biplanes and aerobatics. And,

that's what two-place machines are all about

|

Buying a used 'Bolt?

It's hard to know how many Skybolts have been built, but it is certainly

in the hundreds. Considering that it is a huge project, as any homebuilt

project is, it is "huger" by virtue of the fact that it's

a biplane and a big one at that. Still, many have been finished

and are offered for sale. When considering this route, remember

that these are homebuilt airplanes and, unless they used major components

from Steen, you have to consider the craftsmanship of the individual

building it: not everyone is a Hale Wallace, in that regard. Also,

make sure they followed the plans rather than getting creative,

when they don't have the engineering background to know what they

are doing. Also give preference to airplanes that are as close to

factory specs as possible, in regards to weight. If an airplane

is way under priced, if you check closely, you'll find there is

a reason why and you should probably walk away from it. |

|

Thinking About

Building a Skybolt?

First, go take a cold shower. When dried off, take another one!

Building an airplane, any airplane is a major project and you're

looking at 3,000-4,000 hours to build a Skybolt. Minimum! Nothing

about it is complicated, but there is a lot of it. No different

than any other airplane its size. Buying components from Steen Aerolab

increases the price, but it also increases the probability that

you'll finish it.

You don't need 250 hp to make the airplane fly

well, but, if using a 180-200 hp Lycoming, the airplane will fly

much better if you really keep it light. Weight is almost always

the result of careless application of paint and carrying around

interiors and instrument panels that are far more than the airplane

needs. Remember, if it's not in the airplane, it can't break and

if it's not in the airplane, you don't have to lift it.

|

|