WACO

METEOR/S.F. 260

And still Champeen!

Story and photography by Budd Davisson, Air Progress, Sept. 1977

Editors note from 2006: The Siai-Marchetti S.F. 260 has matured into the aeronautical version of another Italian form of speed, the Ferrari. And like the Ferrari, the Marchetti is a timeless form with timeless handling. But it wasn’t always as well known and it wasn’t always known on this side of the pond as the Marchetti 260 (short hand version).

When it first hit these shores, believe it or not, but it was known as the WACO Meteor. Only three were imported under that name and because they were little known, they wound up either orphaned in hangars or left to rot on ramps. The two you’ll see here are largely responsible for the early rise of the breed because of their airshow activities and appearances in lots of magazines, including posing for one of only about a half dozen covers I shot for Flying magazine, which is hardly my normal venue.

It was through the Marchetti/Meteor that I was first exposed to a special breed of pilot that is so rare, it’s hard to explain exactly how good they are. These two, the late Larry Kingry (only cancer would possibly have enough power to slow him down) and Harry Shephard still rate as two of the finest pilots I’ll ever meet and Larry is easily one of the most unusual characters any of us will ever know. So, when this was written (1977) we were still pretty naive, but we were also pretty damn good. It’s hard to believe we would learn so much in coming years. Incidentally, if I ever hit the lottery, within 24 hours I’ll have an S.F. 260B in my hangar. Count on it!

Waco Meteor owners have a favorite game they play. It involves sneaking up along side a brand new Bonanza, a Viking or one of the much vaunted Meyers 200D's. Once in position, they look over at the other pilot and smirk a little, challenging them to a race. The challenge is always taken. As the victim buries his throttle in the panel and the airspeed stabilizes, the Meteor driver looks over, smiles and mouths a silent "Bye, bye," He then proceeds to walk away from the other airplane, probably doing a four-point roll just to rub it in. And it's such a visible lurch forward that the Bonanza/ Meyers/Viking owner usually starts checking to see that his flaps are up.

|

|

It's especially humbling to know these two used

to fly hard IFR in this position. |

When speed is the name of the game and the engine isn't being force fed through a turbocharger. the undefeated champion is the Waco Meteor. An Italian thorough-bred with all the classic breeding and ill-manners of a Ferrari Boxer, the Meteor (aka Siai-Marchetti S.F. 260) was born to perform in three dimensions. Although its advertised cruise speed of 215 mph is only marginally higher than that of a new Bonanza or hot-rod Meyers, it's when the airplanes are side by side that one begins to suspect that Wichita advertising agencies have more imagination than facts at their disposal. With only 260 horses at the other end of the goknob, the Meteor can. and frequently does, blow the doors off of every civilian, normally aspirated single engine bird ever made. And that's the name of that tune!

The S.F. 260 was designed and nurtured by one of the world's very few true geniuses in high performance light aircraft design, Stelio Frati. Not hampered by a bureaucratic or corporate hang-up that demands all aircraft be designed to be flown by the absolute weakest link in the pilot community, Frati always designs an airplane to get the most performance out of the least horses. And he always succeeds. His airplanes are considered "hot" by most pilots, because they don't land at 50 mph and don't necessarily forgive the pilot if he's cross controlled all his turns within 5 knots of Vso. He designs beautifully exciting machines that go places and only ask that the pilot learn to fly, not drive, before he hops in and straps it on.

In the mid-1960's, an

enterprising and energetic gentleman in Pennsylvania decided to try a new

approach at building an aircraft empire. Rather than building aircraft, he

decided to pick the best designs Europe had to offer and import them under

the name WACO. Most of his choices were regrettable, if not forgettable. Only

the Socata Rallye (Waco Minerva) and the S.F. 260 (Waco Meteor) offered anything

not already obtainable in the American aviation marketplace, and even then,

the Minerva was marginal. The Meteor/S.F. 260 was not. Flown by various pilots,

most of them women, it immediately set several class records and showed the

way around at most of the races in which it was entered.

Unfortunately, the WACO Corporation floundered. Their products weren't necessarily

suited to the existing marketing environment and more importantly, were expensive

as hell. A 1969 brochure lists the S.F. 260 at $33,975 with nothing but wings

and an engine as standard equipment. To make a long. agonizing story short

and agonizing, the importing business went under, the founder passed away

and three S.F. 260's found themselves orphaned a long way from home.

After a few years, the three Meteors suffered different fates. The original

demonstrator. N730W, tired after having been raced, demonstrated and abused,

eventually wound up in the weeds at Whiteman Airpark in the upper San Fernando

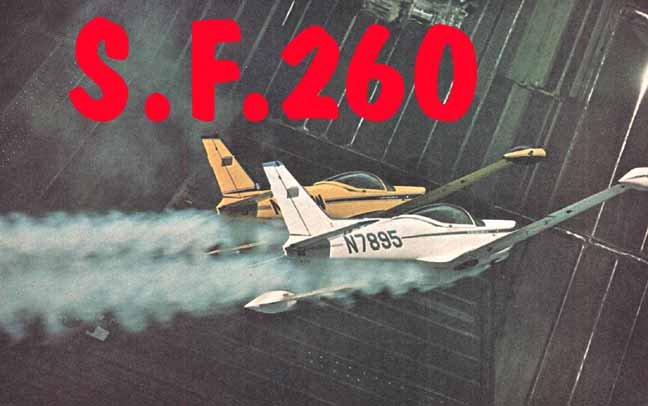

Valley. N7895 belonged to a lady who loved it so much she seldom flew it and

it gathered dust and only 75 hours flying time in the first 5 or 6 years of

its life. The other airplane went from owner to owner before coming to rest

in Columbia, S.C., where its current owner. Bob Russel airshows and salivates

in it.

I guess I could be credited with saving 730 Whiskey from the bone yard. 1

spotted it at Whiteman, looking as forlorn as an Italian can look when stripped

down to its skivvies and left on a deserted ramp. I mentioned it to a hotrock

friend of mine who was looking for something with some zip, and within three

weeks it was back here on the East Coast, with Larry Kingry trying to pump

some life back into it. Then his partner, Harry Shepard, couldn't stand it

any longer so he went to Connecticut and bought N7895. the low time beauty

with only 75 hours. To shorten another extremely lengthy story, they spent

about a year pumping avionics and grotesque amounts of cash into their airplanes

to put together a formation acrobatic team, known locally and variously as

either "The Bobsy Twins" or "Captain Crunch and Precious Little."

|

|

This was early in their career before they started

doing loops and rolls canopy to canopy with their vertical fins over

lapping. |

However, the Waco Meteor

story doesn't end right there, with three bastard machines stranded on foreign

shores. In recent years, two more have been imported by private individuals

who have a speed addiction, one of them based with The Bobsy Twins (properly

ShepKing Enterprises) at Andover-Aeroflex Field in New Jersey. Then, as if

you can't keep a good machine down (you can't) the brilliant history the S.F.

260 earned as an advanced trainer for various European air forces, caught

up with it, Now it is being marketed by Vantage Aircraft Corp. of Washington,

D.C., as a military multi-purpose machine for the Banana Republics. In this

role it has hard points for rockets or weapons pods, a taller rudder, jettisonable

canopy and the other accouterments needed to make a pretty civilian into a

nasty looking gunslinger. This machine will be available to bucks-up civilians.

The price isn't clear; however, it may be something like $130,000.

As it happens, I'm so close to the New Jersey Waco Meteors that they have

to move my Pitts every time they want out of the hangar. That's close! Harry

and Larry and their yellow and white S.F. 260's are legends around the airport

because of what they are capable of doing with their machines. As it happens,

to do their airshow routine has required them to teach their Meteors to eat

via injection systems and Christen inverted fuel and oil systems. They also

went to counter-weighted props. This has taken them out of standard category

and put them into experimental. No bother, though, since that allows them

to do their own maintenance, if necesssary.

|

|

'Just doesn't get any prettier, does it? |

I don't know how many

times I've gone ripping cross-country with them, an extra tip tank painted

right in the middle of our windshield, since they don't feel safe flying further

than three or four feet apart. I've also spent a fair amount of time flying

both airplanes and on occasion have soloed Larry's when we had more airplanes

than pilots and I was pressed into service. However, I had always done only

what was necessary to do what had to get done, including the usual side trips

into rolls, loops and the like. It wasn't until recently that Harry got around

to giving me a proper checkout and let me play around with the airplane, experimenting

with its flight envelope and learning its good and bad points. Andbelieve

me, it's got plenty of both.

Mechanically, the weakest part of the Meteor is its landing gear retraction

system. It's super sensitive to rigging and even the slightest amount of adjustment

creep results in some very expensive noises. As if to prove a point, Harry

pointed out that his is the only one of the original airplanes not to have

been on its nose after the nose gear collapses on roll-out. The culprit is

an adjustable. spring loaded actuating rod that is either easily bent or misadjusted

The up locks also required some updating and the yellow bird of the duo had

the unfortunate distinction of having its gear come banging out during a four

G pull out, which ruptured everything within reach of the actuator mounting

brackets.

Because a Meteor sits so low, it's easy to check the fuel (18 gallons in each

tip, 13 in each main) but you have to slither around on your knees to get

under it to check sumps, gear wells, or clean the residue left by the smoke

system off the belly.

Climbing up on the airplane requires you to watch, where you plant your tootsies

because the wing walks are narrow, too narrow. More than one would-be passenger

has died an unnatural death when Harry caught them with their heels out on

the wing paint. You get down into the cockpit fighter style, hanging on the

windshield frame and swinging down in, guiding your feet down into the tunnel

under the panel. I've flown the airplane from both sides, but much prefer

saddling up on the right side because it feels absolutely obscene to be flying

with a stick in your hand and the throttle in the right. There is a factory

option, which all military versions have, that includes left side and center

mounted throttles so both pilots use their right hand on the stick.

Both of the Bobsy-Twin Meteors have been equipped to the hilt with every known

gadget you can put in a panel, including course-line-computers and, in Harry's

case, an auto-pilot. Not your average airshow machine here. Because of that,

it takes a while to spot the more necessary stuff like flap and gear switches

because they are innocuous little electric jobs that get lost in the blizzard

of switches. Since everything in Harry's panel is where Harry wanted it, there

isn't much purpose in describing the layout, since it is far from typical

Meteor.

The emergency gear extension system, which almost all Meteor owners find use

for occasionally, could stand improving. In the first place, you have to remove

a sizable section of the console between the seats. Then you are supposed

to crank for a specified number of turns, which Harry says is impossible to

do because you lose count when flying and cranking at the same time. Also,

the crank works through the electric motor, so a frozen motor would do the

same for the entire system. One nice aspect of the gear, although sort of

unusual for a high performance airplane like the Meteor, is that the wheels

protrude slightly when retracted. So, the belly just barely touches if it's

dropped in gear up.

Getting the big Lyc going requires a game called "Will it or won't it?"

Usually we're successful. but if it's hot, it takes some playing around. Boost

pump for a few seconds, mixture out. crank it over and hope it catches. When

it does, you are immediately aware of the small size of the airplane in regards

to the size of the engine. The machine is smaller than a Cherokee, with 260

horses to drag it down the taxiway. You also feel the engine weight on the

nose wheel because steering requires a healthy foot or two.

Where the engine/ airframe size ratio really impresses you is on takeoff.

Dropping the hammer gently by screwing in the vernier keeps you from getting

into too many torque problems, but no matter how you do it, it rockets down

the runway with a rush that's guaranteed to fill your hip pockets with adrenalin.

It wraps the airspeed up like a toy but at no time gives any indication that

it will fly off in a three-point position. At 80 mph you pick the nose wheel

off and it still sits solid on the rapidly disappearing runway and doesn't

fly itself off until around 90 mph. I can't verify that number because not

once did 1 catch the airspeed under 100 mph. once I had lifted the nose wheel.

About 12 degrees of flap

is used for takeoff and the unusual thing about them is that you can jerk

them in just as you would the gear. The second you're off the runway the gear

comes in and so do the flaps. The airplane is accelerating so quickly that

any tendency to mush when the flaps come up is unnoticeable because the airplane

sheds drag and picks up speed as they are being retracted.

Except that it happens in one hell of a hurry, the takeoff only requires carefull

attention to keep the centerline wired and to gently urge the nose wheel off

at 80 mph. From that point on, the Meteor is climbing so hard and fast that

all you have to do is hang on. To get the airspeed down to a dangerous level

would take a real knucklehead because the normal climb attitude is terribly

steep. If you put the nose where you would most other airplanes, You'll be

climbing at about 125 mph. One interesting thing about its climbout is that

it will easily top 1500 fpm at 90 mph which drops back to 600 fpm at 125 mph.

However, you can increase the speed all the way up to 155-160 mph at 25 inches

and 2500 rpm and still be climbing at 600 fpm. That's some kind of cruise

climb.

At altitude, the airplane can really reach inside you and grab you where it

counts. In the first place, I found that in using the old stand-by power settings

of 23 inches and 2300 rpm, we were indicating a solid 194 mph. At our altitude

and temperature that'd be about 210 mph TAS. The advertised top speed on the

machine is variously quoted as 215-225 mph but during a timid, closed course.

official run, both Shepard's and Kingry's airplanes hit 234 mph, which nearly

agrees with the handbook sea level max of 235 mph. When flying formation with

a cruising Bonanza or 210, we'd find that we were almost never using more

than 19 or 20 inches of manifold pressure. 55 percent on this airplane gives

something like 175 mph indicated! It's frightening! On a standard day, I've

gone scooting over the top of the New York TCA at 200 mph indicated at 75

percent. The Meteor sure can compresss geography!

But speed is far from being the Meteor's only virtue. I don't know of any

Frati designs that aren't acrobatic and the Meteor certainly falls in that

category. Its high-jinks are of the high speed category . . . big swooping,

incredibly smooth loops and rolls. Hammerheads are absolutely surrealistic,

because you can actually see the horizon creep up the tip tank and stop, asking

you to boot the rudder. You can come wafting over the top of a loop and just

gently tweak the stick and the airplane obediently breaks, snap rolling lazily,

but precisely into whatever you want. Going down hill. it packs mph into the

gauge so fast it's scary and it'll touch the 274 mph redline with only a little

urging. Speeds of 250 and 260 mph arc completely usual and you can suck it

up into a vertical roll from that speed that almost puts you out of sight

of the ground. It has power, it has speed, but most importantly, it has grace.

It also has all the handling characteristics of a fighter. At extremely high

speeds the usually responsive, but slightly hard ailerons turn to concrete

and large deflections require muscle. Also, with only 108 square feet of wing

area and a gross weight of 2430 pounds, it has a wing loading of 22.5 pounds,

which is 30 percent higher than a Bonanza and is equal that of early model

Spitfires.

Its 64 series laminar wing asks that you treat it gently because even a slight

amount too much g at slow speed will send you tumbling over the peak of the

lift curve into a sharp edged stall. Power off, at one g, dirtied up, the

stall will be clear down around 62 or 63 mph. But just the slightest amount

of pressure, like flaring too late and jerking, will run the stall speed up

to 75 mph or better.

There is a reasonable amount of pre-stall buffet that is introduced primarily

by stall strips on the root of the leading edge. Shepard says he once flew

it without those strips and found it' would suddenly stall out from under

you without the slightest warning. Not even a hint of what was about to happen.

Even though he's an exNavy F8 Crusader driver, he put the stall strips right

back on. And the airplane is happiest when flown like a fighter.

When landing, it takes miles to get it to slow down in the conventional manner.

Simply bringing the power back and holding altitude to slow down, will put

you in another country, chugging along at 150 mph with only 15 inches. By

far the best way to get it set up for lauding is to totally ignore the airspeed.

I found it extremely easy to handle the airplane Navy style, flying the pattern.

or parts of it at speeds as high as 220 indicated, then flying a 360 overhead

pattern, sucking it into a hard left turn right over the middle of the runway,

bringing the power back as I did. In that situation the "G" slows

the airplane very handily to the ridiculously low 125 mph gear speed.

Because of the sensitive

nature of the gear, Shepard likes to use 110 mph or slower as a gear extension

speed. Once the gear and 20 degrees of flap are hanging out, keeping the speed

down is no longer a problem. As a matter of fact. it's extremely easy to get

it too slow. Because of the excellent visibility. and the characteristics

of the airfoil and flaps, a slight, almost unnoticeable pitch will steal air

speed like crazy. Conversely, however, you can drop the nose to lose unwanted

altitude on final and the airspeed will almost not move at all. With flaps

that deflect to a whopping 50 degrees it almost has a built-in drag-chute.

It's very weird.

The rate of descent on approach must be astronomical power-off, so a goodly

bunch of horses are kept working at all times in the pattern. 100 mph is a

good number on final with a very solid 90-95 over the fence almost mandatory

for a pilot unfamiliar with the machine. Even when on top of it, 85 mph looks

an absolute minimum over the fence, unless its a very still day. This sounds

high, and it is, but the first time you try flaring it you'll see why you

want that kind of speed.

Even at 90 mph, you can't flare it like a "normal" lightplane without

it suddenly dropping out from under you a toot or so above the ground. 1 don't

know how much speed it takes to make a smooth, almost normal, power off flare,

but it must be over 100 mph. Shepard's method, and one I found comfortable

was to fly it almost into ground effect at a fairly steep glide angle, waiting

much longer than usual to flare, carrying some power all the time. Then, 1'd

flare rather quickly, bleeding the power off at the same time. The combination

seemed to work fine and decreased the amount of time I spent hanging on the

hairy edge of nothing. My earlier approaches,, fairly normal length and glide

angle, required a hell of a lot of power and seemed to demand an inordinate

amount of care while flaring.

Actually. I found the Meteor to be one of the most difficult airplanes I've

ever flown to make smooth landings in. In many ways it felt even more demanding

than a Mustang or Bearcat. both of which aren't quite as critical in ground

effect. It is in no way to be confused with a light airplane, such as a Bonanza

or 210. It is, in every possible way, a high performance, heavy machine and

had better be treated like one. It might let you abuse it for a while, but

keep doing it and sooner or later the airplane will turn around and take a

healthy chunk out of you.

Because of its

high performance style low-speed handling characteristics, later series S.F.

260’s have certain modifications aimed at trying to take some of the

bite out of it. This includes a modified airfoil section out towards the tip

that does away with a little of the sudden break characteristic and gives

better aileron control in and near the stall. The later ones also have a higher

rudder to add directional control needed when weapon pods are being used.

As a traveling. acrobatic, fun airplane, the Siai-Marchetti S.F. 260, aka

Waco Meteor, has almost no equal. Granted it's not a full tour place airplane

because the rear scat is placarded to 250 pounds, but when people start talking

speed the number of people don't seem to count. When it comes to getting there

first, in single engine airplanes, number two doesn't count and number one

will always be a Waco Meteor.

POWER

PLANT

One 260 HP Lycoming 0-540-E4A5 six-cylinder horizontally-opposed air cooled

engine.

Two blade, constant-speed Hartzell type HC-C2VK-1 BF/8477-8R propeller. Two

wing tanks:

total capacity 22 U.S. Gals. Two wing tip tanks'.

total capacity 32 U.S. Gals.

DIMENSIONS

Wing span 27 ft 4 3'4 in Overall length 23ft 3 1/2 in Height 7 ft 11 in

Wing area 108.7 sqft

WEIGHT

Empty weight, equipped 1,664 lb Useful toad 726 lb

Max T.O. weight 2,430 In Max power loading 9.3 lb no Max wing loading 22.35lb/sq

it

PERFORMANCE

Max speed at sea level 187 KTS Max cruising speed 178 KTS Stalling speed with

flaps 60 KTS Rate of climb 1,800 ft/ min Service ceiling 19,000 ft Take-off

run 1,837 ft

Landing run 1,132 ft Range 805 SM

For

lots more pilot reports like this one go to PILOT

REPORTS