It was probably a dawn flight, the early morning haze of a yet-to-develop August scorcher still hanging over the runways, waiting for the rising sun to chase it back out over San Diego bay. Ryan mechanics dropped the cowling panels back into place after checking the little four-cylinder inline Menasco C4S for the last time. The test pilot, John Fornascero, walked around the long, finely tapered wing, casually inspecting an airframe he knew had been inspected and re-inspected a hundred times that morning. Still, it was to be the first flight of a new prototype, the first aerial step of a brand new Ryan airplane into the 1937 world of aeronautics. This was the Ryan SC, a bid to capture the quickly developing personal airplane market. Ryan hoped it would be the rising star of the future.

The Ryan SC died young, after barely a year's production, and is all but forgotten today. Only eleven were produced before the priorities of a growing air force led Ryan to shut down the SC assembly line to make room for the PT-16 and PT-20/22. Several other SCs were completed later from components, which brought the total up to 14 of what could have been a truly important airplane.

To put the SC in proper historical perspective, it has to be viewed against the backdrop of aviation, circa 1937. The Erco 310 (Ercoupe) had just flown and the Dart was about to become a Culver Cadet. Piper was knee deep in Cubs and old man Taylor was about to do his number with the BC-12D. Personal transportation was a two-tiered system of 450-horse super birds (Staggerwings, Reliants) and 65-hp puddle jumpers. There was very little in between. Only the Bellanca junior offered what was then called "high performance;" a cruise speed of 120 mph on 100 hp.

Introduced into this

traditional system of tubing and fabric, spruce and butyrate,

the Ryan SC had about the same emotional impact as Sputnik did

20 years later. From its cantilever, high-aspect ratio wings to

the racer-like panted oleo landing gear, it was a step ahead of

everything else in its class. Of course, across the Atlantic pond

Miles, Percival and Messerschmitt were producing similarly configured

aircraft and enjoying great success, as defined by European terms.

But, here in the U.S. of A. the Ryan SC was a quantum jump in

light aircraft design. It brought the most advanced technologies

of the era to bear on an airplane for the monied masses. Of course,

in 1937, the monied mass was pretty small and a bit worried about

joining the rest of the nation at the neighborhood bread line.

Still, Ryan gambled that progress and personal aviation would

make the SC a winner.

Introduced into this

traditional system of tubing and fabric, spruce and butyrate,

the Ryan SC had about the same emotional impact as Sputnik did

20 years later. From its cantilever, high-aspect ratio wings to

the racer-like panted oleo landing gear, it was a step ahead of

everything else in its class. Of course, across the Atlantic pond

Miles, Percival and Messerschmitt were producing similarly configured

aircraft and enjoying great success, as defined by European terms.

But, here in the U.S. of A. the Ryan SC was a quantum jump in

light aircraft design. It brought the most advanced technologies

of the era to bear on an airplane for the monied masses. Of course,

in 1937, the monied mass was pretty small and a bit worried about

joining the rest of the nation at the neighborhood bread line.

Still, Ryan gambled that progress and personal aviation would

make the SC a winner.

There is today a large number of Ryanphiles that mightily mourn its passing. The number of surviving SCs is variously estimated at seven to ten, which represents a survival rate of an astounding 75°0. If, for instance, Cubs had the same survival rate, you could line them up wingtip-to-wingtip and they'd reach from the Shakey's Pizza at Seward, Nebraska, to Wahoo and back again. Pretty impressive!

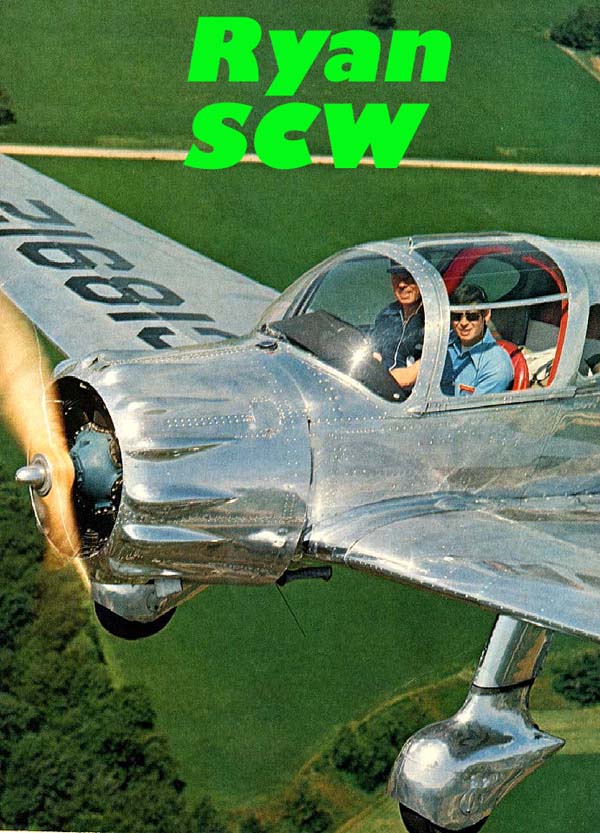

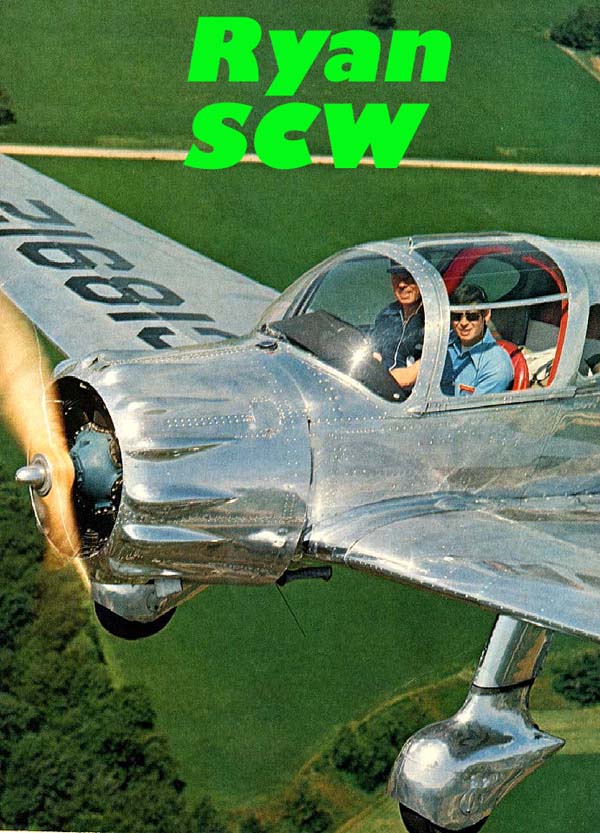

Several of the surviving SCWs have been bastardized with flat engines (after the prototype, all production models had radials) or modified this or that, but Brad Larson, of Minneapolis, liked the airplane the way it was. And that's just the way his SCW looks today, like it was back then, and walking around it is a real education in the supposed progress of light aircraft design.

A casual glance at the leading edges of the wings on Larson's SCW shows that the Ryan engineers weren't taking any chances. Since the leading edge is a stressed-skin torque box and had to carry most of the wing loads, they made even the lightest pieces heavy. The skin, for instance is a solid .040 inch thick, which may not mean much to most pilots, but the same area in even the high-powered bombs these days seldom goes above .032. Almost all of the rivets are gigantic 3/16 jobs and even the smaller 3/32 are much larger than the rivets you'll find in modern aircraft. You almost never see anything bigger than 1 /8 inch rivets on modern airplanes and C-150s are skinned with bushels of tiny little 3/32s. And all that's on exterior skin! The inside must look like the detail work on the Golden Gate Bridge. A similarity to a Wells Fargo cash box is not necessary by modern standards. With decades of light plane stressed-skin construction behind them, today's airplanes are nearly as strong as the SCW, but much lighter, so they don't need all that beef.

But, still, looking at the gentle, graceful way in which the workers at Ryan constructed-no, created-their airplane, you can't help but see the benefits of a little thought. Larson's airplane is a brightly polished collection of sensuous curves that shows none of the waves, the "oil canning" of thin-gauge metal slopped together. Most of the heavier curved surfaces of the SCW were actually formed on dies, and then all holes were drilled using nested steel drilling templates. Almost everything was predrilled before assembly, seldom done today because of the expensive tooling.

The aft portion of the wing is fabric covered

and sales literature of the day said, "This makes possible

a wing which has its natural center of gravity coinciding with

the center of pressure. The latest findings of extensive research

have shown that such a statically balanced wing is the only type

completely free from any possibility of wing flutter under all

conditions." Ignoring the fact or fiction of that statement,

can you imagine seeing that statement in your latest super-slick,

four-color brochure on your 172 or Cherokee? No public relations

firm in its right mind would admit to the existence of something

like wing flutter. But the flying public of 1937 had just watched

Beech go through a shredding wing problem with the Staggerwing

and was a little wary of airplanes that promised high performance

without lots of brace wires.

All of the production SCWs used the 145 Warner Super Scarab radial

rather than the inline Menasco of the prototype. What prompted

the change is hidden in the minds of those who made the decision,

but the outcome was that the incredibly sexy Menasco cowl gave

away to an equally perky little round one for the Warner.

Every airplane has some physical quirk that sticks in your mind long after you've flown it. The door latches on 172s, for instance, have always reminded me of cheap fishing tackle boxes. Beech control wheels leave a good feel in the palm of my hand. With the SCW, the thing that immediately impressed me was the canopy. It opened with a feather touch, the ball bearings gliding back on the canopy rails with a slick, purposeful sound. Quality; that's what this tiny detail said. And attention to one detail usually means all the others are equally well done. The airplane didn't disappoint me.

Brad Larson didn't really restore his SCW.

He bought it 20 years ago, when it was just an unusual airplane,

not a classic antique. Since then all he's done is keep it immaculate

and fly it like he would any other airplane. Hardly a major fly-in

anywhere in the country would be complete without Brad's friendly

smile and shiny Ryan. An airline captain by trade, he'd rather

drone along listening to the rumble of the Warner than the whine

of a gaggle of turbines.

The true personality of an airplane almost never reveals itself

on the first visit to the cockpit. It's only after many hours

hunched glint eyed at the controls that a pilot can say he really

knows and understands the airplane. After twenty years with the

same bird, Larson just grins and says, "She's a lady. An

honest, straightforward machine."

Sliding down into the cockpit is easy with the canopy back; it's a wonder the Yankee and Traveler are the only domestic airplanes to use this method of entry. The airplane is dated by the scattergun placing of the instruments about the panel as well as the trusty old control stick. It's interesting to note that the flaps and trim controls are on the left side of the pilot, rather than the right, which forces him to change hands on the stick. But it keeps the controls out of the passengers' way.

The Ryan is a three-place bird; the back seat is meant to handle an occasional passenger who has masochistic tendencies or short legs, but the front deck is deep and fairly wide. Naturally, you see nothing but cowling when looking straight ahead, but the Warner is so small and the flight deck so wide, that large gobs of runway are easily visible around the nose. When taxiing out, the SCW didn't feel a bit like a pioneer in the industry. But, even though she was a little old, she still had a thing or two that we could use today. One is the throttle control. It's a combination push-pull type and vernier. If you screw it in or out, it acts like a straight vernier, but all you have to do is push or pull to overcome it. There's no thumb button or vernier release in sight. Now, that's the way a vernier should be designed!

The brakes definitely were of pre-war vintage. Working off a so-called

"Johnson Bar", you pull on a large centrally mounted

lever sticking out of the floor. Then, when you push a rudder

pedal down, you get brake in the direction of that pedal.

Okay, line up on the center line, throttle in. Rumble, rumble. The little Warner told me it was doing its best to run us down the runway. Rumble, rumble. Then, with no warning, or coaxing from the controls, the rumble of tires and tin disappeared and was replaced by the warm murmur of the engine and the wind past the canopy. I had been concentrating on the edge of the runway and was so surprised to find it falling away that I quickly glanced at the airspeed and found we had gotten off at 50 mph. Takeoff roll was short, directional control great, and the feeling of airborne contentment overwhelming. It was going to be a good flight.

Without a doubt, the best feature of the SCW is its visibility.

Produced in an era when built-in blind was taken for granted,

the Ryan's aquarium-style cockpit must have really been impressive.

It still has better visibility than almost any airplane in production

today.

Those long, almost unreal wings lift exactly the way they look; beautifully and with grace. Without seeming to work or strain, the little SCW easily climbed at 800 fpm, the wings looking like those of an eagle locked in a thermal.

The long-span ailerons give a quick response, but the same large ailerons that gives quick roll rates also make stick forces on the heavy side. But the airplane is nimble. There is, in fact, a rumor floating around about an SCW that put on an aerobatic demo at Ottumwa a year or so ago and shook up a few of the troops.

With wings tapered like pool cues, you'd expect a sharpish stall with the tips and ailerons going first. Not so. The wing has nearly six degrees of twist as it runs out to the tips, so the stall is much like any other machine that flies. Pull hard enough and it quits flying. Relax and it flies again. No big deal.

The SCW's wings are over 37 feet long and it's not a flyweight at 2150 pounds gross. Still, with 145 radial horses, it purred along at an effortless 130 indicated, which I later confirmed with two-way ground speed checks. That's not half bad for an airplane with the frontal area of a beer keg with overshoes.

As I turned final, I glanced over at Brad. He was smiling, digging on me digging his airplane. He was watching me discover something he's always known; that Ryan built gorgeous air-planes and beautiful experiences with a missionary zeal that belongs to those who truly love flying machines.

Coming down final at 75 mph, I was again impressed by the visibility and then mildly surprised by the high sink rate. Then Brad grinned a little more, and said, "Here, let me give you half flap," and he pulled on the flap lever with mischief in his eye. The SCW doesn't really have flaps, not in the normal sense, anyway. What it has is a large perforated center section flap that is more a dive brake, a fugitive from an SBD. Anyway, the second he yanked on the handle, I found myself shoving the throttle in. Then I shoved it in more and more. My God! What is this? Were we dragging a parachute? Soon I had nearly cruise power on just to maintain 75 mph. I've never seen anything like it! With the flaps out, it flies as if you're trying to drag it through molasses. After touchdown, Brad turned and said "You should see it with full flaps." No thanks.

As is usually the case, I managed to end a

nearly spiritual aviation experience with a totally clumsy, humiliating

flop back to earth. I hadn't bargained for the six-inch extension

of the oleos and managed to kiss off the main gear, getting a

little skip and a hop for my trouble. The gear is soft and squishy

and waddles just a tad when the tail moves back and forth.

The usual tail-dragger tap-dance on the rudders was more of a

ballet, as everything was happening in slow motion, like a stop-action

karate scene. Then, Brad grabbed the brake lever, we turned off

the runway and my flight of fancy and nostalgia was done.

As I slid the canopy back, I once again marveled

at its precision. Then, I hesitated just a second, balancing on

the canopy rail before getting out. I looked around at the oversized

controls, the boilerplate and rivets, the tiny wingtip disappearing

in the distance. Then my feet found the rough black wingwalk and

dropped off the wing to the ground. I'll bet money John Fornascero

hesitated exactly the same way 38 years ago as he stepped from

the cockpit of the prototype. He must have known that he had just

flown one of the finest light planes in the world. Just as I did,

he probably paused to savor the experience, to prolong the feeling.

He was a lucky man and so is Brad Larson. For him the experience

goes on.