|

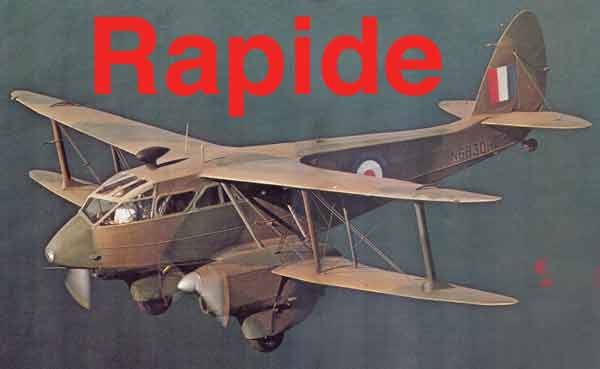

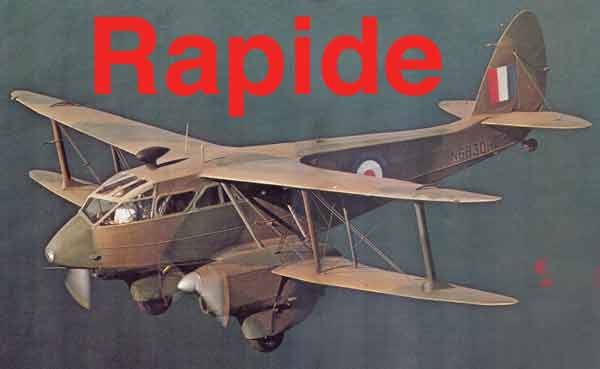

Anachromism, Thy

Name is Rapide |

Hatched the same year as the contemporary DC-2 and the lethal-looking Me-109, the Rapide had been airborne barely a year when another British legend, the Spitfire, first flew. The two don't seem to be from the same world, much less the same technological period. Still, they were comrades in arms, each serving its own purpose. The heavy hand of the Depression was felt around the world during the early 1930s, so when de Havilland decided to build airliners to serve the second-level airline market, it chose a designless path where nothing technologically new was to be tried. All materials, techniques and design theories were to be time-proven, and as a result, de Havilland was using World War I technology to build Rapides in 1946. The first de Havilland aimed at satisfying the need for an economical feederline aircraft was the 1932 DH.83 Fox Moth. It was essentially a Tiger Moth with a cabin for several people built into the belly of the fuselage and the pilot in the usual open cockpit high and behind. Then came the twin-engine DH.84 Dragon an all-new design that carried six to eight people at slightly over 100 mph with a 130-hp Gypsy Major putt-putting away between each wing. Then came the relatively huge four-engine DH.86 Dragon Express that featured two 204-hp Gypsy Six engines on each side and a cabin that seated 10 in comfort. The stage was set for the Rapide.

Through the simple expedient of scaling everything down and using nearly the exact outline of the Dragon Express, de Havilland engineers produced a twin-engine transport that carried six to eight passengers with two 205-hp Gypsy Six engines driving fixed-pitch propellers. The DH.86 Rapide is typical of the rest of the Dragon series; the fuselage is a long box built entirely of wood with fairing strips on the outside covered with fabric for streamlining. The spruce and fabric wings have four ailerons and are braced with a myriad of wires and struts. The result is an aerodynamically dirty airplane that is extremely light for its size: 3,500 pounds with a 48-foot span. With the onset of war, the Rapide became the mainstay of the RAF for transport and liaison flying. There was no way to postpone the war until a better design came along, so the DH.86 Rapide became the RAF Dominie transport. By the time the war was over, total Rapide production was 727 aircraft, and many then became surplus, flooding the market and being used to carry everything from business executives to fish and chips. A transport aircraft usually leads an active life, but it faces a slow, lingering death that begins with a temporary grounding because of the lack of a vital part, followed by gradual deterioration in its role as the weed-strewn airport derelict. It falls, at last, to the whim of a neat-freak, and is cut up for junk. That's why de Havilland's lizard-shaped mini-transports are facing total extinction. Restoring new life to their tired bones is too big a project for the average antique airplane buff to tackle. Of course, Bob Puryear and John O'Brien aren't average antique buffs. Both Puryear and O'Brien are airline pilots based in San Francisco, and while O'Brien wasn't available for comment, Puryear blames him for the idea of getting an antique airplane. Puryear had something like an old Stinson or maybe a Stearman in mind, but O'Brien was thinking along more grandiose lines—and a de Havilland Rapide that was being sold by an aerial company in England and could be bought for a song. Puryear and his wife, Norma, are very active in the Experimental Aircraft Association (they're on the board of directors) and they thought it might be fun to own their own miniature airliner. So, they hopped over to Merry Olde to take a look at the Rapide and fell in love with it on the first flight. Several pounds of shillings changed hands and the O'Brien/Puryear airline was formed. First on the agenda was ferrying the airplane to Doug Bianci's famed restoration shop. There it got a new coat of genuine English camouflage, and the mechanics crawled over it, putting everything in first-class working order, while long-range ferry tanks were installed. The plan was to fly the bird home via Greenland, but weather, red tape and good sense intervened, and the airplane was disassembled and shipped to the States. After its arrival in the United States, the airplane was carted to Newark Airport where it was assembled and readied for the flight to Hollister Field, California. The flight across the country and the stopover at Oshkosh were as smooth and trouble free as if the airplane had forgotten it was more than 30 years old and wasn't supposed to be useful. |