|

| The rudder trim is supposed to be 6 degrees right on takeoff. |

PAGE SIX

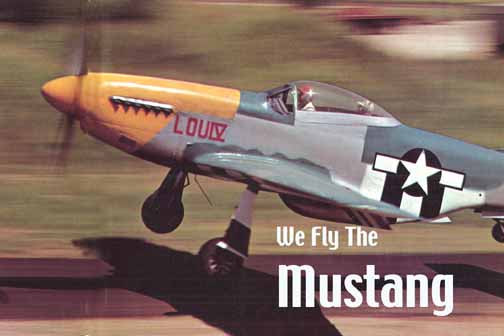

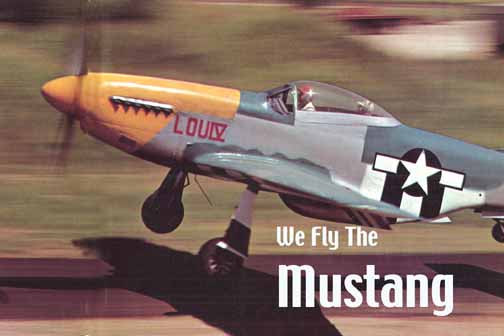

Burchinal's Mustang is a P-51 D and is painted in the colors of Col.

J.J. Christiansen of the 479th Fighter Group, 455th Fighter Squadron,

Eighth Air Force, European Theater of Operations. Christiansen and

his Louie IV were shot down over France in 1944, but they are well

remembered. No chronicle of the Mustang is ever complete without at

least one picture of the colorful Louie IV.

One of the additional advantages of flying with junior Burchinal is that

you are bound to be personally involved in some of the never-ending

maintenance that warbirds need. This is especially important to the

guy who intends to buy one and it is interesting to any redblooded

warbird nut. Besides learning how to service the Mustang, checking

coolant, oil, leaks, and so forth, junior fills you in on all the little

details that are nice to know if you want to operate a warbird.

As it was bound to, the big day finally arrived. Today I was going to

launch in the Mustang. Since there's only one set of controls in the

Mustang, you only get one go at it, and it had better be good. All

that Junior can do is explain procedures thoroughly and have you ride

around in the back for a while getting a feel of it, and then let you

go. He put me in the back and we went out to see how the aircraft does

certain things. We did stalls and torque rolls, none of which really

helped me because I was just a passenger and I couldn't appreciate

what was necessary to keep things under control. He did impress me

by slowing to 100 mph and adding power until he was out of right rudder

and the airplane was still slewing left. The Mustang has a power-on

Vmc just like a twin-engine airplane, but it only has one engine. With

a lot of power, it takes speed to make the rudder effective enough

to overcome torque and P-factor.

We headed for Cox Field, Burchinal's practice airport, and I knew things

were getting close. He shot a couple of landings with me perched on

his shoulder like a gremlin, trying to learn as much as I could secondhand.

He even had me reach around him and make turns with ailerons only so

that control effectiveness wouldn't come as a surprise when I made

my first flight. He talked to me-correction, yelled to me-all the way

through his approaches trying to tell me what was happening. He flew

the approaches exactly as we had in the SNJ except that the numbers

were much faster.

Then it happened. He pulled over to the side, climbed out, and said

go fly it—just as if he were soloing a kid in a Cherokee. He

said something about me doing fine, but I couldn't be sure because

my heartbeat drowned him and the Merlin out completely. Actually, I

was quite calm, all things considered. We had talked, and trained,

and flown, aiming everything at this moment, and I felt prepared.

The Mustang taxied easily into position, squarely between the two white

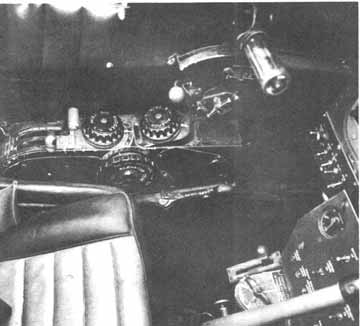

centerlines. Prop forward, flaps up, boost on, tank on right. A thousand

hangar tales raced through my mind at one time—maybe I was a

little scared. Torque rolls, screaming swerves, 1,450 horsepower. I

once again noticed where the horizon split the spinner for future reference,

and started moving the throttle slowly forward. I really didn't mean

to start the takeoff roll, but I couldn't think of anything else to

check. I was out of excuses and eager to fly.

Visibility was excellent and I began feeding power in more rapidly because

I was eating up runway like crazy. More left arm, more power, more

noise. Anything you hear about a Mustang's cockpit noise can be believed.

It ceased to be sound and became a pressure, forcing against my eardrums.

My right foot nervously twitched at the right rudder, coiled, wired,

positively aching to trounce the rudder to the floor the minute the

long skinny snoot started swerving, as I knew it must. Thirty inches,

thirty-five inches, forty inches. My right arm tired of trying to hold

the tail on the ground. It was going to come up despite anything I

could do, so I neutralized the stick and the tail blew off the ground.

As the nose leveled out, howling its way toward the other end of the

runway, it was suddenly as if I were standing up in the airplane; the

visibility was tremendous. My eyes darted back and forth from one side

to the next, keeping the long line of Dzus fasteners in the center

of the cowl lined up with the expansion joints in the pavement.

At 45 inches, it suddenly felt as if it were dragging me forward and

I was being rammed toward the tail, a helpless passenger strapped to

a cannon ball that was going to pull me through space. Noise, noise,

noise! At 50 inches, 55 inches, my foot still pressed lightly, but

firmly on the right rudder.

When was I going to get the chance to play Mustang driver and fight to

keep the nose straight, mashing the rudder to the floor, using brake

when the rudder was gone? When was the torque going to become the uncontrollable

genie all the big guys talk about? Suddenly, it was off the ground.

I'm flying a P-51! Whooee! They could hear me in the next county.

Back

to business. By the time I was off the ground and had a chance to check

the airspeed, I was already passing through 140 mph. The program called

for me to stay in the pattern for the first flight, leaving the gear

down. On the next flight, I would clean it up and go out into the area

to hunt FWs. Bringing the power back to Burchinal's supereconomy climb

settings of 29 inches and 1850 rpm, I held 130 mph and banked easily

left onto crosswind. At this low speed the controls are extremely light,

maybe even a little soft. Even though I was terribly slow, the airplane

felt extremely solid and comfortable-and so strangely familiar.

I was sitting on top of the world-in my own private little bubble. In

level flight on downwind, visibility was totally unrestricted, but

things were getting a little busy for sight-seeing. Flying an aircraft

with a wing loading of over 45 pounds per square foot and a general

reputation of gliding like a cast-iron frisbee, I was really afraid

to reduce power. I considered leaving 30 inches on and driving it onto

the ground, but I knew that the second I lowered the nose I'd be charging

around at 200 mph. The Burchinal Method is three-point or forget it,

so I figured I'd stay with the program and have at it. The airspeed

showed 130 mph when I ran my 35th GUMP check.

I gingerly brought the power back a bit, and reached back with my left

hand to shove the flaps down two notches. The nose tried to pitch down,

but the stick forces are so light that my right hand automatically

came back, maintaining an attitude that came out as 130 mph while I

rolled in enough trim to hold it. I kept an anxious vigil - airspeed,

manifold pressure, altitude. I was still carrying about 20 inches when

I turned base and slowed to 120 mph. I kept waiting. When was the bottom

going to fall out like a real fighter? So far it had acted like a lady,

flying as if it were on rails. Roll out on final, twisting my arm again

to grab the rest of the flaps.

Oh, oh, here it comes. I rolled a little up trim and jumped up to the

throttle as we sink just a little low. I figured I had to catch it

or it would fall to the ground like the proverbial rock. I was afraid

of the throttle. It's a dynamite plunger that all the books say will

roll you on your back if you even touch it. But I was low and I had

to add power. I eased the throttle forward, intending to keep my arm

moving as fast as necessary to keep from bouncing off the Texas landscape,

right leg ready to jump. The left hand started moving and the sink

stopped just as quickly. What's this? It flies on final just like an

airplane.

Well, the ground was coming up and the worst was probably yet to come.

Burch said 100 to 110 over the fence, so the power came back a little

more and the stick did the same. While I was doing this, I suddenly realized

I could see the runway right over the nose! Even a Citabria is blinder

than that! The numbers disappeared; I had it made. The power was all

the way back, and the Merlin barked in protest. As the runway came up

to meet me, it didn't seem a bit different from the SNJ, except I could

see what's going on. I leveled out what I figured to be a foot or so

up and the airplane surprised me by actually floating. Here I was in

a solid brick of aluminum and it had a bit of float to it.

As it tried to settle, I brought the stick back until the horizon split

the nose exactly where it had when I sat in it all those hours logging

cockpit time. I was in a three-point attitude; all I could do now was

wait until I hit the runway. Just as on every approach in the SNJ,

I moved my feet up to get better leverage on the brakes and got ready

to kick. A slight bump, two from the tail as the tailwheel skipped,

and we were down and rolling straight, me and the Mustang. Was that

it? Wasn't it going to careen down the runway, letting me live up to

the superpilot image?

With the stick in my lap, that steerable tailwheel made the rollout almost

Cherokee simple. One thing is certain: the P-51 doesn't want to stop

running. Even on the ground, it gives up speed very grudgingly. I pulled

on the throttle several times to satisfy myself that I wasn't carrying

just a little power. I was in no real hurry to stop, so I just let

it roll, using very little brake at the far end of the 5,000-foot runway

to make the turnoff.

While still rolling straight, I pushed the stick hard forward, unlocking

the tailwheel. Once on the taxiway, I reached back and brought the

flaps up and rolled the canopy open. Rolled the canopy open! I couldn't

believe it! For a lifetime I had dreamed of it, and now I had done

it. I had soloed a Mustang!

GO TO PAGE SEVEN

For lots

more pilot reports like this one go to PILOT

REPORTS. |