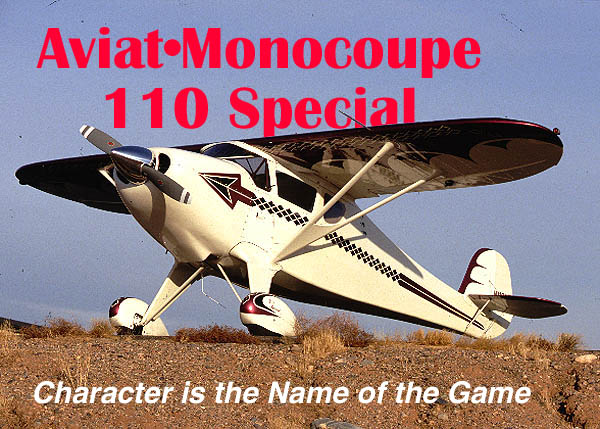

Right up front I want to make an apology: I want to apologize to Stu Horn, Aviat's president, and all the folks up in Afton, Wyoming for what I was thinking the first time I saw their version of the legendary clipped wing, Monocoupe 110 Special. I looked at that tiny tail, the non-existent windshield, the tall narrow gear and I was thinking, "Man that thing is going to be a real lunch eater. They're crazy if they think they can sell those things to mere mortals.!" Now, having flown the airplane I know how deceiving looks can be and how far off base I was. I apologize because, while the airplane isn't going to be everyman's idea of a great airplane, to someone who wants a fast, fun flying machine that truly has a character all its own, the Aviat 110 Special is certainly it.

When I finally got my chance to fly the airplane and was in the process of doing this incredibly graceless stretching exercise called "climbing on-board", I couldn't help but remember pilots inspecting the airplane at its introduction at Oshkosh '99: they quickly separated into two camps. One was shaking their heads, clearly amused with just a hint of fear in their eyes. The other group however, had fire in their eyes and it was all they could do to keep from drooling. Like we said, not everyman's airplane.

When viewing Aviat's new airplane, a pilot has to remember several things. First, the clipped wing version of the Monocoupe, the 110 Special, was originally supposed to be a pylon racer with Johnny Livingston at the controls and it's designed to fly that way. Second, people were smaller in those days. The forgoing facts mean that both big wings and big cockpits were unnecessary. The first time you sit in the airplane, you'll also assume they thought windshields were unnecessary as what there is of it is well above your head.

The cockpit is narrow. Probably one of the narrowest of any two place airplane being offered for sale. That's just the way airplanes were designed in the late 1920's. Aviat, to their credit, however has come up with an interesting solution: rather than going with the original thick, wood doors, they designed a nifty steel frame door that's less than an inch thick and adds close to three inches to the shoulder and hip room. So, now it's tight, but not uncomfortably so. The door also hinges upwards with a nitrogen assist cylinder that works beautifully. It makes getting into the airplane much easier than with the original doors and does away with the need for a jettisoning mechanism which will be necessary when it is approved for aerobatics. Still, doing some stretching exercises would be a good idea before trying to board. They say a step is being designed, which should help.

The cockpit also has

a thoroughly antique feel to it. For one thing, the top edge of

the instrument panel is almost even with the top of your head

because of the steep deck angle. More interesting, the only part

of the windshield that isn't covered by motor is a tiny sliver

at either end of the slightly concaved instrument panel. However,

even though the windshield is virtually useless in the three-point

position, the airplane somehow doesn't feel much blinder than

many other taildraggers. This is because the fuselage tapers towards

your feet just after it goes past your shoulders which moves the

front door post inboard giving amazing visibility out the side

windows. No, you can't even remotely see ahead, but the view angled

out about 30° to the side on which you're sitting is quite

good. The visibility the other way, across the cockpit is also

non-existent, which brings up an interesting point: When taxiing

it takes the tiniest turn away from your side, to uncover the

entire taxiway ahead of you. "S" turning is not only

unnecessary but it doesn't work because you have to turn really

sharp, probably 60°, the other way to see out the opposite

side.

The cockpit also has

a thoroughly antique feel to it. For one thing, the top edge of

the instrument panel is almost even with the top of your head

because of the steep deck angle. More interesting, the only part

of the windshield that isn't covered by motor is a tiny sliver

at either end of the slightly concaved instrument panel. However,

even though the windshield is virtually useless in the three-point

position, the airplane somehow doesn't feel much blinder than

many other taildraggers. This is because the fuselage tapers towards

your feet just after it goes past your shoulders which moves the

front door post inboard giving amazing visibility out the side

windows. No, you can't even remotely see ahead, but the view angled

out about 30° to the side on which you're sitting is quite

good. The visibility the other way, across the cockpit is also

non-existent, which brings up an interesting point: When taxiing

it takes the tiniest turn away from your side, to uncover the

entire taxiway ahead of you. "S" turning is not only

unnecessary but it doesn't work because you have to turn really

sharp, probably 60°, the other way to see out the opposite

side.

Ed Saurenman, Aviat's Chief Designer/Engineer and all around aviation junkie, lit the fire on the IO-360 A1B6, pointed at the control stick, indicating I had command, and away we went. There were no brakes on the right side but I didn't miss them. The tailwheel is moderately tight and the airplane tracked exactly the way my feet moved. No more, no less. With the exception of having no idea what was on the other side of the airplane, it was a cinch to taxi. Almost like a go-cart.

We'll ignore the first take off because the right door, mine, popped open at about 60 mph and I aborted the takeoff. Ed says they've flight tested the open door up to 160 mph IAS, but I wasn't all that interested in taking off with the door hanging out at a 45° angle. In the process, however, I got a good feeling for the airplane's ground handling in a less than optimum situation: besides accelerating almost up to takeoff speed with a door open and wind hitting me in the face, I had Ed Saurenman laying across my lap trying to close the door. At no time did the airplane do anything stupid. I was the one who did something stupid in not getting the locking pins completely set. The next takeoff was more successful.

The vernier throttle

(more on that later) doesn't have to move very fast to get a terrific

reaction out of the airplane. I eased the power in and got the

airplane rolling then pushed it the rest of the way and held on.

The engine is exactly the same as in my Pitts and we were carrying

the same number of people, but the acceleration was easily half

again what I see out of my own airplane. I think I had adrenaline

pooling in my boots.

The vernier throttle

(more on that later) doesn't have to move very fast to get a terrific

reaction out of the airplane. I eased the power in and got the

airplane rolling then pushed it the rest of the way and held on.

The engine is exactly the same as in my Pitts and we were carrying

the same number of people, but the acceleration was easily half

again what I see out of my own airplane. I think I had adrenaline

pooling in my boots.

I was watching the side of the runway out my window and, as the tail came up, I didn't have time to re-focus my eyes over the nose before we leaped off the ground. But this was not a lift-induced leap. This was the ballistic launch which is part of flying tiny airplanes with big motors. What a rush! It would be worth buying one of these things just to do that over and over.

The instant we came off the ground, the left wing came up and I pressured it back down while playing with the rudder to keep my butt in the middle. The airplane doesn't have a skid ball and doesn't need one. Even though we were sitting almost on the CG, it was amazing how much you could feel the airplane skid when it wasn't in trim. On every takeoff the wing would could up and I couldn't figure out why. Finally, I asked Ed and he said it was because that tank was empty and the airplane was so sensitive to loading that wing simply flew first.

Usually, I climb a strange airplane out at a flat angle to get better visibility but, since we'd have to be dead level to see over the nose, I just held it at 100 mph and watched the ground rapidly disappear out my side window. The specs say the airplane will climb at 1700 feet per minute and I wish I had timed it because that's what my Pitts climbs at and this was going up noticeably faster. The airplane is definitely a rocketship!

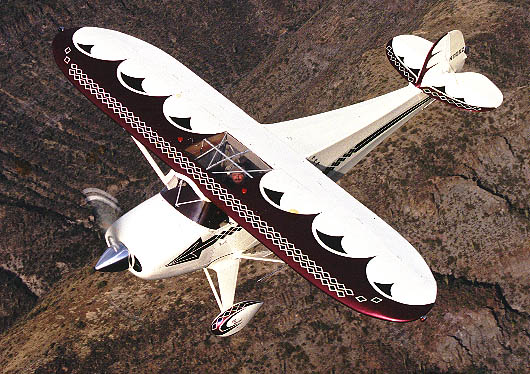

As I pushed over into level flight, the visibility got better and better until it was almost normal, but I had to duck my head to look under the wing for side visibility. Turns in either direction felt much better, if I picked up a wing to clear the area first. As I played with the controls I could see that they had done quite a bit with the ailerons in trying to get away from the traditional heavy, scratchy feel of original Monocoupes. They'd changed some linkages to give the stick more mechanical advantage, but were still limited in travel by leg room. Ed said as soon as he got the airplane back to the factory, they were going to design a control stick with a higher pivot point so they could increase the mechanical advantage through the system even more. The pressures are acceptable, as is, but everyone, Aviat included, would like to see them lighter.

Ed had said it was a "rudder airplane" but it wasn't until I started messing with the controls that I saw he wasn't kidding. As I was turning, I was consciously trying to coordinate and was paying special attention to what I was feeling. There was a lot of slipping and skidding I was compensating for but it wasn't until I tried separating the controls to do a turn without rudder that I figured out what was happening. Prior to flying this airplane, I'd always thought the Aeronca Chief to be the King of Adverse Yaw, but it doesn't hold even a very small candle to the 110 Special in that area. Using enough aileron to pull a wing up 15°, with out rudder, results in the nose going the other way while the airplane ignores the entire process and continues straight ahead indefinitely with the nose off to one side. In a 15° bank, it would absolutely refuse to turn without rudder. Just tap the rudder, however, and it would come around smartly. I then found I could lock the stick in neutral and put in the tiniest amount of rudder and it would roll into the nicest, most coordinated turns I've ever done. Tap the rudder harder and the airplane would snap into a bank almost instantly. Old Johnny Livingston wanted to turn corners and this airplane would definitely do that. The roll-yaw couple was by far the strongest I've ever seen.

Let me make one thing

clear here: even though the feeling that you have to constantly

play with the rudder is initially strange, this is no way a negative.

It's just an unusual characteristic you get used to in a few minutes

and you can fly along indefinitely with your arms crossed while

flying the airplane just fine with your feet.

Let me make one thing

clear here: even though the feeling that you have to constantly

play with the rudder is initially strange, this is no way a negative.

It's just an unusual characteristic you get used to in a few minutes

and you can fly along indefinitely with your arms crossed while

flying the airplane just fine with your feet.

If you walk the airplane back and forth with the rudder then let go of the rudder, it immediately locks up in the direction it was pointed and sets up a fairly steep spiral and it doesn't make any difference whether you freeze the rudder or not. Again, not a bad characteristic, but one worth noting.

After they got the airplane back to the factory and listed all the comments made by journalists and prospective dealers who had flown the airplane they made a number of significant modifications. Their goal was to make the airplane handle in a more normal manner. The mods included increasing the size of the vertical tail (a big percentage increase but you still can't see the difference). They put spades on the ailerons and changed the linkage to give more mechanical advantage. I talked with Ed about the changes in some detail and he says it completely eliminates any of the airplanes "strangeness" and any pilot would find it to be very normal feeling. He also said the ailerons are not only much, much lighter, but the already spiffy roll rate was even higher. Alright!

I couldn't check the pitch stability because the bungee trim system was out of whack and was constantly biasing the elevator slightly. The elevators, however, felt completely normal.

The airplane is really fast for the power. We were indicating right at 170 mph at 23 square and Ed says he flight plans 175 mph and always gets it. He also says he thinks the airplane has another 20 mph in it. Just prior to leaving the factory, a mechanical glitch had forced them into replacing the Hartzell composite two-blade with a conventional, and shorter, metal prop. Ed says the instant they did that they lost 8 knots in cruise. Also, since its Oshkosh introduction, the airplane has been under going constant modification including lowering the cowl line nearly 3 inches. This changed the windshield angle and, when Ed and I got together, the fairing strip at the top of the windshield was still the original and had a huge amount of drag-producing gaposis. He's confident they'll have the airplane cruising effortlessly at 190 mph or more before serial production begins.

I was interested in how the airplane would stall, so I chopped the power and held the nose slightly high. Then, I pulled and waited. Then, pulled and waited some more. The airplane didn't want to slow down and, as it came down through 85 mph, it REALLY didn't want to slow down. Eventually somewhere in the high 60's, with little or no buffet, those tiny wings suddenly unloaded, the nose fell and it rolled off on a wing. It has a very clean break with not a hint of a mush. The instant I released back pressure, however, it was back flying, even before I brought the power up. The book stall speed is 68 mph and the wing is the good old fashioned Clark Y.

When stalling the airplane I was careful to keep things centered as they haven't done the spin test series yet. For that reason we couldn't do any aerobatics. This was a disappointment because Woody Edmunson in his 110 Special "Little Butch" helped set the stage for serious aerobatics in the late 1940's. Once the spin tests are completed, however, the airplane will once again be able to dance, which I imagine it will do really well. I couldn't measure the roll rate, but when you put your shoulder into I'd guess it at something around 150°/sec.

As we came back into the pattern, I was feeling much more comfortable in the airplane because I found the rudder-only thing made it much easier to handle. However, as we slowed down, I once again had to put some aileron into the mix. Ed had said to use 110 mph for the first approach (100 is normal) and I found it dead simple to put it on an IAS number and keep it there. It was terrifically speed-stable throughout the approach even though we weren't using trim.

Visibility isn't an issue during the approach. Not at that speed, anyway. The runway sits in that tiny windshield, which doesn't seem that tiny after the first hour, and lets you drive right down final. It was about half way down final that I got yet another surprise: the airplane really wants to glide. I had expected it to fall out of the air the second the power came back and the prop flattened out, but it didn't. In fact, I was coming in too high to hit the numbers.

As we floated down the runway, I started flaring and, as the nose came up, I automatically shifted my eyes to the runway edge visible in the windshield sliver at the edge of the instrument panel. As the nose came up further, my eyes kept tracking back until I was once again looking out the door window. It all seemed very natural, although I don't like looking at just one side of the runway to land. I prefer glancing at both.

I held the airplane

off and it floated and floated, then gently touched and hopped

a little in three-point. I didn't rush the throttle, but waited

to play with the rudders as it slowed down. Again, the airplane

followed my feet and, with the runway edge so clearly in sight,

it wasn't hard to see the changes needed. I was using very little

rudder and the airplane was giving no indication it would do anything

I didn't ask it to.

I held the airplane

off and it floated and floated, then gently touched and hopped

a little in three-point. I didn't rush the throttle, but waited

to play with the rudders as it slowed down. Again, the airplane

followed my feet and, with the runway edge so clearly in sight,

it wasn't hard to see the changes needed. I was using very little

rudder and the airplane was giving no indication it would do anything

I didn't ask it to.

Power up, we scrambled back into the air. What a blast! If the sun wasn't just about to set, I could have kept doing that until we ran out of gas.

On the last landing, I was a little slow getting the tail down and we kissed gently off the mains setting up a little skip. Not wanting to drop it in, I thought I'd ease in just a hint of power. I got the hint of power in but forgot about that stupid vernier throttle (a friend of mine is taking up a collection to fund AAVT, Aviators Against Vernier Throttles) and I didn't get the hint out until it touched again. And again. And yet again. Do I get to log all those landings? Through out the entire embarrassing episode, the airplane was absolutely honest and not once did I feel any centrifugal force against my seat telling me the airplane was trying to turn hard. I gave it every opportunity possible to take a chunk out of my behind and it just trucked ahead and did it's thing.

I don't know if the Aviat 110 Special is indicative of all such Monocoupes or not, but I was impressed by its ground handling. It's honest and direct and is very, very much like a Luscombe, yet another airplane with an undeserved reputation. The only reason a pilot would have serious trouble with it would be because he over controlled it and didn't realize the airplane was only doing what he told it to do. The lack of visibility and the rudder would take a little getting used to but that's all minor stuff.

The airplane is really intriguing in that it is an honest to goodness modern antique that is useable. It has four hours worth of gas and can shuffle along at a healthy clip and let you arrive in style. Here's an airplane for the antique buff who wants the appearance and fun of an antique but wants to go places at the same time without worrying about something breaking and letting him down. It's a new antique for the new millennium.

Aviat Monocoupe 110 Special

Power Plant Lycoming IO-360 A1B6, 200 horsepower

Wing span: 23'10"

Overall length: 19' 10"

empty weight: 1160 pounds

Gross Weight 1624 lb.

Vne: 207 mph

V cruise, 75%: 173 mph

Vstall 68 mph

Rate of climb: 1700 fpm

Range @ cruise: 475 miles

Fuel Total: 42 gallons

Baggage: 20 pounds

Aviat Aircraft

672 S. Washington

Afton, Wyoming 83110

(307) 886-3151

FAX 886-9674

Tell them you saw it on Airbum.com