It was interesting to stand around the airport when the airplane

was on final. "Gee, I don't know, it has a little Navion

in it but it has a tail wheel and look at the width of the main

gear!"

Every time Bob Evans showed up at our local airport, at least

two individuals would ask what kind of an airplane he was flying.

Bob would answer "A Meyers 145" and in answer to the

blank look and the next question ~ . only about 20 were built!'

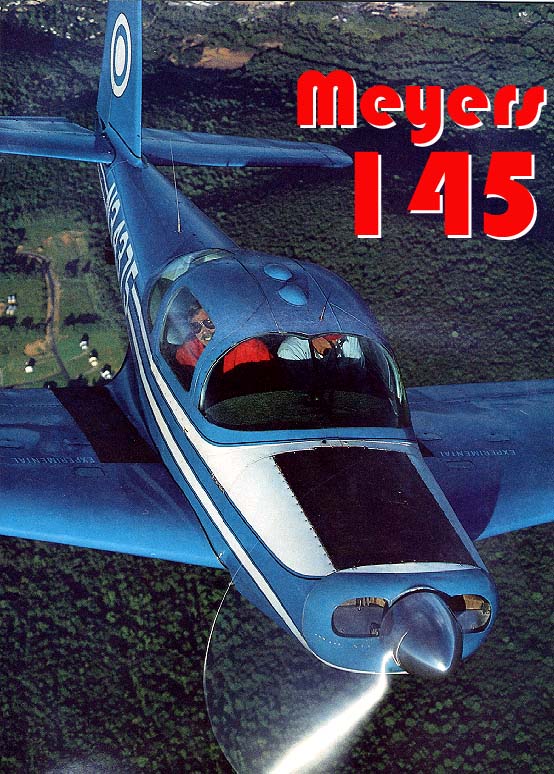

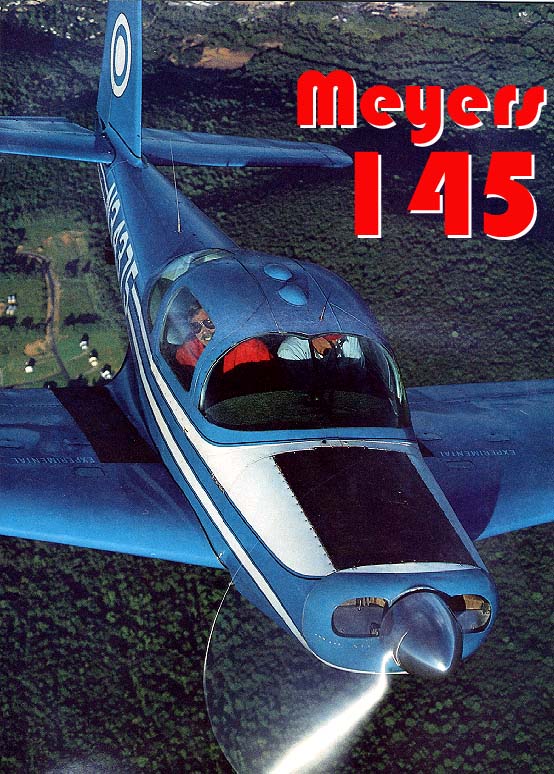

The airplane's perky look and wide stance seem to attract just

about everybody, but there are few who can identify the airplane,

even fewer know the airplane's place in the Meyers' line of unique

aircraft.

If nothing else can be said about Al Meyers' airplanes, they can definitely be defined as distinctive appearing. But their distinction goes far deeper than simple looks. Their safety records are practically legend: Supposedly no cadet was ever killed in a Meyers OTW biplane trainer during WWII and enthusiasts of the breed quickly point out there are no ADs on any of the later airplanes - the 145 and 200. If true, that's impressive considering the Mey-ers line spans a quarter of a century.

The Meyers 145 was the second of Al's designs and differed wildly from his OTW (Out To Win) biplane CPT trainer. It has to be pointed out that the OTW, as dainty and vaguely stalky as it looks, broke new ground in many areas. The most obvious departure from the norm is the OTW's aluminum monocoque fuselage. Another feature is the tremendous gap of the wings, which makes the slender fuselage seem even skinnier and makes the airplane fly better because of reduced wing interference...but it was the soul which Meyers built into the airplane that made it a legend. The 0TW was a gentle airplane possessed of practically no bad habits; it was a gentleman through and through.

WWII did its share of damage, but

in its wake was an abundance of technological advancements that

would have taken decades - rather than months - to develop and

perfect, had it not been for wartime urgencies. One of the advancements

was the use of aluminum in aircraft. What had been the exclusive

territory of the military (with a few notable exceptions) and

the airlines, suddenly became a common knowledge shared by many

involved in the war effort. Now practically everybody knew how

to design monocoque aluminum structures. Al Meyers became one

of those.

WWII did its share of damage, but

in its wake was an abundance of technological advancements that

would have taken decades - rather than months - to develop and

perfect, had it not been for wartime urgencies. One of the advancements

was the use of aluminum in aircraft. What had been the exclusive

territory of the military (with a few notable exceptions) and

the airlines, suddenly became a common knowledge shared by many

involved in the war effort. Now practically everybody knew how

to design monocoque aluminum structures. Al Meyers became one

of those.

Like so many others of his day, Meyers expected the returning pilots to want to retain the mobility they had enjoyed as military aviators. So he took what he had learned and designed an airplane that would be a sports car for those pilots. He knew everyone else was designing trainers or touring sedans, so he aimed for the discriminating taste that wanted performance and handling in a pretty package. His design was called the MAC-145: Meyers Air Craft, 145 horse Continental.

In one area Meyers differed greatly from his peers: He didn't rush headlong into an inventory producing production rate. Because of this he has been called a realist or a shrewd planner. In reality, since production of the 145 didn't start until 1948, he had the opportunity to see the early postwar years weren't living up to expectations in terms of aircraft sales. By being late with his design, he avoided the fate of so many other manufacters... namely, he didn't build up acres of unsold airplanes and avoided inevitable bankruptcy or reorganization.

On the other hand, maybe Al Meyers WAS a realist and a shrewd planner, because he immediately took the sheet metal capabilities of his smallish plant in Tecumseh, Michigan, and started building consumer items that were salable in postwar years. Jeep tops were one of his main-stays and the same plant today builds "Tecumseh" boats. The MAC-145 was but one of a number of Meyers products and it was one he didn't start hammering on until a customer had already walked in the door and asked for the plane. In other words, he had a production line that ran only on a custom order basis.

The up-front order approach is one reason there were only 20 145s built between 1948 and 1955. It is also a reason Meyers made a profit on every one he built and that may be an aviation record!

In describing 145s, one has to recognize there is no such thing as a standard airplane. Since the plane was custom-built, each 145 is different. On top of that, because of the "sporty" mentality of those attracted to such an air-plane, most have been modified to fit the personality and missions of the owners but they all share the same basic back-bone and airframe.

The 145, like the following Meyers 200, utilized a "composite" airframe with steel tube structure in addition to the aluminum monocoque assembly, from gear to gear and firewall to back of cabin is a welded steel tube truss. Although labor intensive, this structure gave the airplane a crash-survivability index much higher than one made entirely of aluminum. Meyers proved this with the prototype while spin testing the aircraft. Reportedly he inadvertently jettisoned the door while reaching for the spin chute to recover from the flat spin. Since the door was open and the spin was flat, he apparently decided that would be an excellent time to be somewhere else and bailed out. The airplane augered in from 10,000 feet while in a full flat spin. Meyers trucked the wreckage home, peeled off the aluminum, did a little welding and used the center section, cabin tube structure and starboard landing gear for the second prototype.

The beefy wing and tail structure were all bolted to the tubing truss with a metal fairing structure covering the cabin. If not told he was wrapped in a steel tube cocoon, the pilot would have no way of knowing it was there.

Safety was always one of Meyers' real goals and ,even though it was designed as a high-performance bird fox high-performance pilots, the 145 has a couple of interesting safety features: When the gear is up, rudder travel is restricted. When flaps are up, the elevator is restricted. Reportedly this feature was to reduce the possibility of accidentally spinning the airplane. The probability of that actually happening, when the airplane is clean, is negligible but it sounds good in theory.

Although only 20 airplanes were built, 18 are known to still exist with over a dozen of them flying. That is a unheard of survival rate for any airplane, especially one designed for old fighter pilots. However, spread the 12 to 15 airplanes out across the US and they are few and far between. Spotting a 145 ranks right up there with the Pink-Eyed Periwinkle Bullfinch. When I saw the seldom seen and so-distinctive wide-geared silhouette of a 145 on final, even though I had already left the airport and was headed home, I had to turn around and investigate. I wouldn't do the same for a Periwinkle Bullfinch!

The gentleman climbing out with a big smile on hi face introduced himself as Bob Evans from just over the hill in Allentown, Pennsylvania. And yes, he'd be delighted to show me his airplane. In fact, 1'm certain he would be delighted to show anybody his airplane. Meyers owners seem to have a certain zealous approach to life and have a need to show other pilots what they are missing.

As it happens, we missed each other

for nearly half a year before our schedules meshed and I saw the

little dreamboat sitting on our ramp at Andover, New Jersey.

As it happens, we missed each other

for nearly half a year before our schedules meshed and I saw the

little dreamboat sitting on our ramp at Andover, New Jersey.

Sharp-eyed Air Progress readers will recoginze N34375 as an airplane we did a pilot report on only 16 years ago! Gene Smith did the honors then and I've always been jealous of him, so I hope no one objects to us running reports this close together.

As it happens, 375 went inactive less than a year after we did the 1972 story and it stayed that way until Bob Evans bought the semi-dormant corpse from well-known Meyers merchant Gid Miller in 1985. A Champ came along with the deal. The Champ is sold and the Meyers is back flying.

As it now stands, 375 is almost exactly as it was in 1972. Bob hasn't had a chance to really restore the airplane since it has taken all his time to get the Meyers back into the air. Someday he plans on doing a real number on the 145 but, until then, he's just enjoying flying.

Walking around the airplane there is nothing other than the prop to indicate a 210 horse Continental has replaced the original 145 hp unit. Some other Meyers have had the same conversion, but 375 was the first. It is also the only one still flying in the experimental category since the original owner didn't finish the paperwork for the one-time STC. Bob will get to that "sooner or later!'

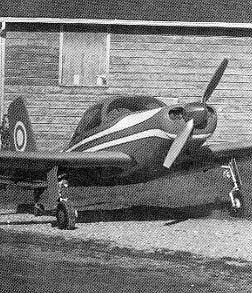

Climbing into the airplane, I followed my usual practice of flying from the side that puts the yoke (some 145s had sticks) in my right and throttle in my left. In a strange airplane I need all the help I can get and feel more comfortable that way. In the Meyers, that left Bob with the only set-of brakes, which made taxiing the airplane a cooperative effort since it has a non-steerable tail wheel.

Entering the airplane isn't too difficult, since the door wraps partially over the roof, but Bob cautioned me about hanging onto the top of the windshield when letting down. Apparently the structure is a little weak and it's a good thing he mentioned the fact because the top is the logical piece to grab ... in fact, it is the only thing to grab, which complicates getting in just a smidgen.

Once in, I slammed the door and whacked myself in the head. Some aviator! The headroom is barely adequate for my barely adequate height, so six footers must be tight. I'm not sure this is typical, because I've seen taller guys in the airplane and they didn't brush the overhead. Maybe Evans' seats have been modified for more visibility.

Cranking the Continental, Evans motioned for me to take the controls and I dropped my left hand where the throttle vernier should be, and was. But so were three other verniers: The prop, mixture, throttle and elevator trim are all lined up side-by-side. Interesting! I'd have to remember that before making any rapid movements.

Visibility is what would be expected:

Marginal over the nose, okay out to the side. The original prototype

flew with a much shorter tail wheel strut, which must have made

visibility really terrible. In this configuration visibility isn't

any worse than other taildraggers, but with the short strut? Forget

it!

Visibility is what would be expected:

Marginal over the nose, okay out to the side. The original prototype

flew with a much shorter tail wheel strut, which must have made

visibility really terrible. In this configuration visibility isn't

any worse than other taildraggers, but with the short strut? Forget

it!

At taxi speeds, the rudder didn't do much so I had to ask for "right brake, a little left" and I knew initial takeoff would be a similar situation. I was keeping these facts in mind as we completed the run-up, bent 15 degrees of flap out and lined up on the runway. I brought the power up slowly and smoothly and found the right rudder nailed to the floor almost immediately but it was having no affect. "Right brake" and everything straightened out. As soon as the speed built up, and even before the tail was up, the rudder had enough air going over it to do some good. Prior to that, the takeoff was a brakes-only operation.

Not knowing anything about the airframe, I just trundled along at a slightly tail low attitude, figuring the 145 would eventually decide to fly - which it did somewhere around 70 knots. As soon as we were on the way up, Bob said he'd get the gear and I nodded. At that point I didn't know what getting the gear meant.

Bob yanked on a sizable aluminum lever between the seats to select "gear up;' then started pumping rhythmically on a much larger lever alongside the first one. That was the hydraulic pump responsible for bringing the gear into the wells. Fourteen pumps later (actually we kept losing count, but that's close), I checked the window under my feet and saw no daylight, which meant a wheel was blocking the view and all was right with the world.

By my clock we were climbing about 1400 feet a minute, which is nearly twice what a stock 145 does and is one of the prime reasons most folks go to the bigger engine. At about 1450 lbs empty, and 2150 lbs gross, 145 ponies have to work awfully hard. Although Evans' airplane picked up nearly 100 pounds in the conversion, it appears to be well worth the weight in takeoff and climb improvements.

Leveled off, I reached for the trim vernier (after carefully making sure which one it was) and gave a healthy twist. Immediately the yoke heaved up in my hand and I knew this was a very effective trim system, well-suited to a vernier since any normal amount of trim input would be entirely too much.

With the nose at level, I let the airspeed build before bringing the throttle and prop back to 24 inches and 2450 rpm. At that setting, things stabilized out at about 165 mph indicated which is almost exactly what the 145 timed out at across the ground during two-way speed checks.

The air was something less than friendly, although the turbulence was relatively minor. Still, the Meyers showed a tendency to wallow around just a little, doing a "Bonanza Boogie" for me. The 145 could use some fin area, something others must agree with since some of the flying Meyers have dorsal fins.

I came to the Meyers 145 knowing very little about the plane, so it was with total innocence that I chopped the throttle and held the nose above the horizon while feeling for the stall. As the speed came down into the low 60s, there was a pronounced buffet. Then, holding through the buffet, the airplane unloaded like a Bearcat and tried to drop the right wing like a wall safe. Immediate relaxation of back stick and coordinated left rudder and aileron cured the situation with no delay, but it was still a surprising stall. I found later it has a 23015 airfoil tapered to 23009 at the tip and the stall I saw was very characteristic of the sharp lift curve belonging to the NACA 23000 series airfoils. It's a fast airfoil with little pitching moment, but you pay for this fact at the low end.

The controls were smooth and had a definite Beech feel to them. The elevator, however, had a certain amount of "float" where at neutral it could be moved a small amount with no effect. This could have been slop in the control system, since much of the airplane had the feel of needmg some fine tuning, something Bob agrees with.

Coming back into the pattern, down and dirty, Bob cautioned that the airplane would really settle. Keeping that in mind, I flew a reasonably tight pattern and found him absolute-ly right. Although I was at a normal height on final for just about any other airplane, I started carrying more power. Using the throttle, it was easy to draw a straight line to the approach end of the grass.

What was not easy was figuring out how high I was in the flair. The airplane feels as if it sits fairly high and I tried to compensate while reaching for the ground in a three-point attitude. At about ground-plus-a-foot, the 145 decided it had had enough of that foolishness and deposited us on the runway with a little thump. No hop, no skip. Just thump and we were there. The airplane seemed fairly willmg to go straight ahead until the wind went out of the tail at which point I told Bob it was his airplane since he had the brakes.

On the next landing, I tried a wheelie and found it to be kiddy-car simple. Just drive the 145 down final, level out and let the Meyers do the driving. Still, the brakes were needed almost as soon as the tail came down. Given my druthers, I think I'd three-point the 145 most of the time but, in a good crosswind, this is one airplane I'd nail to the runway on the main mounts every time.

It's easy to get tired of the term "classic!' We all apply the term to just about everything that came out of the post-war years, since these aircraft have a little of yesterday and little of today in them. Oddly enough, the MAC-145 doesn't feel or look like a classic because it just doesn't seem that old. Except for the tail wheel, the airplane is much more "today" than it is "yesterday" which is what probably makes a classic a classic but, with the most minor of modifications, the 145 could have come out of the factory last year and we'd never know the difference. (Editor's note from the year 2000: guess I was right, since the Micco is the old 145 put back into production with a much needed bigger engine)

It doesn't do much good to pine for an airplane repre-sented by only 18 examples and for which there are probably 100 would-be owners for every actual owner. That doesn't stop pilots from appreciating the airplane, and there is a lot to appreciate.