I twisted to my right, looking back into the Lear's cabin where my woman was curled up sleeping in the back seat. Smiling, I returned to business, banking slightly left to look below. Marrakech was slipping by under the left tip tank, and I thought, what the hell, we didn't have to be in Stockholm for another twenty-four hours, so why not drop down and visit friends wintering there? Marlene would enjoy the sun and we'd make Sweden with plenty of time to spare. 1 brought the power back to 73 percent and popped the spoilers, triggering the four quick stabs of up-trim I knew it would need. In seconds I was dropping through 30,000 feet, then 20,000, then 10,000. As I got lower I noticed Marrakech looks a lot like . . . Augusta, Kansas, tank farms and all.

Begrudgingly I let my daydream slide away, sighed a disappointed sigh, and banked around to make a long straight-in to Wichita Muni. We can't all be rich, but we can all dream, and a short hop in a Learjet plants the seeds for a lifetime of dreaming. Walter Mitty, move over!

Right now somebody, somewhere, is saying, "Budd Davisson is a rat fink. He's sold out and gone over to the big airplane side." No I haven't sold out. I still champion the cause of the little airplane people, but when the chance to fly a jet comes along, who am I to refuse? I had completely given up any idea of ever playing with one of those propellerless things and was content to knock around in Citabrias and such. I was, and am, a hard-core pasture pilot, but I guess the powers-that-be figured I could give an unbiased, naive view of the world of the bizjet. They loaded my cameras, packed my toothbrush, tied a little tag, with my name and destination on it, around the second button of my shirt, pointed me at Wichita, and said, "Have at it, kid."

How did I find the

Lear? In two words, it's a real mind blower! In the first place

it's so sexy it should have an "X" rating, with nobody

under 18 allowed aboard. It's not so big that it becomes a BIG,

big airplane, but it's big enough to be comfortable. The most

impressive thing about the Lear is that it performs even better

than it looks. If it looks fast sitting on the ramp, you ought

to see it at altitude.

How did I find the

Lear? In two words, it's a real mind blower! In the first place

it's so sexy it should have an "X" rating, with nobody

under 18 allowed aboard. It's not so big that it becomes a BIG,

big airplane, but it's big enough to be comfortable. The most

impressive thing about the Lear is that it performs even better

than it looks. If it looks fast sitting on the ramp, you ought

to see it at altitude.

I'd never had the chance to play with high performance aircraft like this and I wasn't really prepared for it. During takeoff and initial climbout I'd been in back photographing another Lear glued to our wing tip. Then I moved up to the flight deck, surveyed the panel and sorted out the dials, trying to figure out what each one meant. Hmm, 4,000 feet in four or five minutes, not nearly as good as I expected. I glanced at the ground and it sure seemed a long way down so I rechecked the altimeter again. Of course dummy, it's 14,000 not 4,000. That IS good! Wait a minute, the little tiny hand is past the two, not under it. My God! That thing says 24,000-ft and it hasn't been five minutes since we broke ground. 24,000-ft! I couldn't get over it. My folks live just across the border in Nebraska and I wanted to wave and yell "Hey, ma. Look at me. 24,000!" Talk about wrecking my head.

The Learjet was hatched

by Bill Lear, the world's resident big idea hatcher. Lear comes

up with a fantastic idea, the world tells him he's off his nut,

then he goes out and does it. Electronics, airframe mods, autopilots,

steam engines, you name it and Bill Lear has done it. The bizjet

came up in the early '60s, and he was originally working the thing

out with a design team in Switzerland. It was to be called the

SAAC-23 and was patterned after a fighter-bomber called the P-16

(I don't know what it is either, but that's what it says in the

folder public relations gives to the press). The project was moved

to Wichita and the first LJ (as it's known to the in-crowd), a

model 23, flew on October 7, 1963. As time went on, Bill Lear

decided to go elsewhere to try a few new screwball ideas, and

Gates Rubber Company bought him out, making it the Gates-Learjet.

The Learjet was hatched

by Bill Lear, the world's resident big idea hatcher. Lear comes

up with a fantastic idea, the world tells him he's off his nut,

then he goes out and does it. Electronics, airframe mods, autopilots,

steam engines, you name it and Bill Lear has done it. The bizjet

came up in the early '60s, and he was originally working the thing

out with a design team in Switzerland. It was to be called the

SAAC-23 and was patterned after a fighter-bomber called the P-16

(I don't know what it is either, but that's what it says in the

folder public relations gives to the press). The project was moved

to Wichita and the first LJ (as it's known to the in-crowd), a

model 23, flew on October 7, 1963. As time went on, Bill Lear

decided to go elsewhere to try a few new screwball ideas, and

Gates Rubber Company bought him out, making it the Gates-Learjet.

For the 1970s Lear (or Gates) is producing four basic models: the six passenger 24C and D, and the eight passenger 25B and C. The new models will incorporate a window per passenger and numerous internal modifications. Personally I like the older oval windows, but I forfeited my vote when I asked them if the plane was covered with ceconite.

The bird I flew was a leftover 24D that had the older windows, and I climbed all over it looking at the goodies they cram into it. It isn't often that a grass cutter like me gets a chance to actually touch a Lear, much less really poke and pry into its innards.

The Lear looks clean

from a distance, but right up close it's absolutely sterile. It's

fantastic how clean the bird is, but then it has to be to go that

fast. One of the most interesting features of the exterior is

the bunch of little gizmos poking up out of the outer wing panel.

The Lear people said they were vortex generators, and I suspect

they were performing some sort of flow straightening function

to make things line up before the air came to the ailerons (Davisson

guess number 347). The leading edges of all the surfaces, including

the jet inlet, are bare polished metal to reduce erosion of the

paint and to allow the electrically heated deicer units to work

better.

The Lear looks clean

from a distance, but right up close it's absolutely sterile. It's

fantastic how clean the bird is, but then it has to be to go that

fast. One of the most interesting features of the exterior is

the bunch of little gizmos poking up out of the outer wing panel.

The Lear people said they were vortex generators, and I suspect

they were performing some sort of flow straightening function

to make things line up before the air came to the ailerons (Davisson

guess number 347). The leading edges of all the surfaces, including

the jet inlet, are bare polished metal to reduce erosion of the

paint and to allow the electrically heated deicer units to work

better.

The wings are wet, in addition to the tip tanks, and there's a fuel pump every-where you look. There's an auxiliary for starting, one on each engine, a couple out in the tip tanks, and the tip tanks will gravity feed down to 50 percent in case all the pumps fail (fat chance). The systems have back-ups for the back-ups. The gear, for instance, can be blown down by a compressed nitrogen bottle, which means you aren't going to have to bend your bird if your hydraulics go away. The controls are conventionally operated with old-fashioned cables and push-rods so they work regardless.

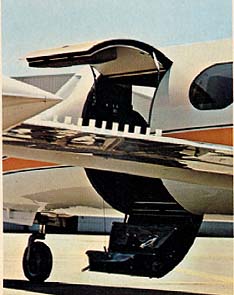

The door is like something out of a bank vault. The reason it's so massive and complex is that it's a load carrying part of the structure. It locks into the door frame with a bunch of lugs that are engaged with a Star-Trek-sounding Nnnnnzzt as an electrical drive unit is energized. The bottom half folds down into an airstair door.

Okay class, how many of you know what a chine tire is? I didn't. It's a nose tire with a ridge about two inches high sticking out where the white sidewall should be. It operates as a deflector to keep from kicking sticks and stones up into the intakes. Without the chine you have to have a deflector installed.

The outside of a Lear has all sorts of gadgets the average pilot doesn't usually have to worry about. The angle of attack vane is conspicuous in its location forward of the door and probably looks like a good place for the boss' dumb secretary (who always travels with him on all "business" trips to Acapulco) to get rid of her double wad of Juicy Fruit. I found in reading the manual that the nylon nubbin right on the apex of the radome is a spray nozzle for deicing alcohol.

The panel is crowded, but once you figure out what's what, it's only about twice as complicated as the average. Actually, if you eliminate all the electric do-dads, and radar, and all that other necessary avionics nonsense, there are only a few gauges not normally seen by the recip driver. The engine rpm is read out in percent and is usually used as an indication of how much power is going out. A better power indicator is the pressure ratio gauge, that tells you how much extra boost the engine is giving the incoming air; it came in at such and such a pressure and went out so much higher, two to one or something like that. Across the top of the panel is a bunch of those little lights that have warning signs like "tilt" printed on them. They go on and off like a Christmas tree during starting and warm up.

Every Lear that comes out of the factory is equipped to fly itself. It's got autopilots that will do everything but put sugar in your coffee. It's got a stick shaker unit that forces the nose down if you get it too slow, pulls it up if you get too fast, and even eases off the pressure if you try to pull too many Gs (about G above normal). Scary!

In flight the first thing you notice is that letting the nose move up and down just the tiniest bit results in gains and losses measured in thousands of feet rather than tens. I finally got it nailed down to where I could hold plus and minus 200 feet, but I ducked my head once while Bob Barry, the check pilot, explained something to me, and I came back up to find I had soared 1,500 feet into positive-controlled airspace.

The ailerons are fairly light, but they aren't nearly as light as Learjet likes to think they are. Being a grass roots type I have the advantage of at least knowing what really light ailerons are (Zlin, Jungmeister), and the Lear's are good, but don't compare. Rudder isn't needed because the yaw damper automatically takes care of coordination unless you turn it off intentionally.

We were streaking

along at 24,000 feet at something in excess of 400-mph. Optimum

cruise altitude is 41,000 (my typewriter nearly choked when it

wrote that number) and it's supposed to do 508-mph TAS, .81 mach.

It doesn't seem like you're moving that fast, but I don't remember

the towns in Kansas being that close together before either.

We were streaking

along at 24,000 feet at something in excess of 400-mph. Optimum

cruise altitude is 41,000 (my typewriter nearly choked when it

wrote that number) and it's supposed to do 508-mph TAS, .81 mach.

It doesn't seem like you're moving that fast, but I don't remember

the towns in Kansas being that close together before either.

Probably the most impressive single thing is the way it climbs. Most bizjets have to step climb; you go up so high, burn off some fuel, climb some more, burn off fuel, etc. In the Lear you just point your nose up and go: 12 minutes to 41,000 feet! Those numbers don't mean much until you figure it would take less than two minutes to reach a 140 Cherokee's service ceiling at the Lear's climb rate, and less than 10 seconds to reach pattern altitude.

Cabin pressure can be controlled to come down at a normal rate, like 500-fpm, so you can let the LJ fall out of the sky like a manhole cover and not rupture any ear drums. It will go down just as fast as it goes up. You can put the spoilers out (trimming for them with a super-sensitive electric thumb trim) and drop the nose, coming down at red line speed.

I was really surprised at how easily I could control the speed in the pattern. At our weight and configuration the approach was made at 118-mph, and I didn't really have to fight it to keep it. In a jet the glide slope is maintained more by changing the nose angle, than by jockeying power. It's just the reverse from what you learn in training. The jet drivers tend to control speed with throttle, and altitude with attitude.

The Lear has one

really weird characteristic that nearly drove me bats. As the

speed comes down through 150, it starts to dutch roll gently.

It will bank a little one way, and when you correct, it goes the

other way, so that you waggle your way down final like a student.

I never did get it completely damped out, and I've had experienced

jet drivers say they had the same experience. Here again, Lear

tries to say that it's control sensitivity, but it's definitely

not. It feels more like inertial effect of all that tiptank weight

so far out. As you feed in aileron to set up a desired roll rate,

it starts to roll and then rolls a little faster as it overcomes

its inertia. When you correct it, the same thing happens in reverse.

You could get used to it eventually, but it would mean that you'd

have to learn to limit the amount of aileron you fed in during

each correction.

The Lear has one

really weird characteristic that nearly drove me bats. As the

speed comes down through 150, it starts to dutch roll gently.

It will bank a little one way, and when you correct, it goes the

other way, so that you waggle your way down final like a student.

I never did get it completely damped out, and I've had experienced

jet drivers say they had the same experience. Here again, Lear

tries to say that it's control sensitivity, but it's definitely

not. It feels more like inertial effect of all that tiptank weight

so far out. As you feed in aileron to set up a desired roll rate,

it starts to roll and then rolls a little faster as it overcomes

its inertia. When you correct it, the same thing happens in reverse.

You could get used to it eventually, but it would mean that you'd

have to learn to limit the amount of aileron you fed in during

each correction.

Bob warned me I'd probably try to flare it high, so I mentally told myself to drive it right into the deck and show him I really had the makings of a hot-shot torch jockey. No go. I flared high any-way. Since there's absolutely nothing out in front of you, and the gear is short, you literally have to stick it in the dirt before you bring the nose up. As the nose came up, the power came back (we carried better than 70 percent all the way down) and we were down, but good. With the spoilers out there was no doubt that we were on for good and I hopped on the brakes. The brakes are unique in that they have an anti-skid device built into them, so that no matter what the surface you can stand on the pedals, and the brakes will grab just short of a skid and then hold at that point and no higher. It's impossible to lock the wheels.

I can see why it takes about 15-20 hours to get a type rating for a jet. There's an awful lot going on in a short space of time and it could easily get away from you. The various schools get about $4,000 for a type rating, or $50 an hour if you just happen to have your own Lear lying around. I'd say it's money well spent. With a base price in excess of $700,000, the training is no place to be trying to save a nickel. (Editor's note from the year 2001: look at those prices!! Where did we go wrong?)

I was impressed by the Lear in nearly all areas. It's comfortable, reasonably easy to fly (considering that it's a jet) performs like crazy, and is so quiet all you hear is a slight whistle. When you compare all the numbers and the economics, the Lear is obviously the way to go if you're seriously in need of getting there in a hurry without a whole lot of company. On the other hand, it's just plain groovy to sidle up to one and lean on one wing, looking slightly perturbed, as if your girl is late arriving again, every so often squinting up at the sky. If you're lucky, you can fool all the kids by the soda cooler for as long as 15 minutes until the owner comes and chases you away. It's really a machine for day dreaming.