Page Two

|

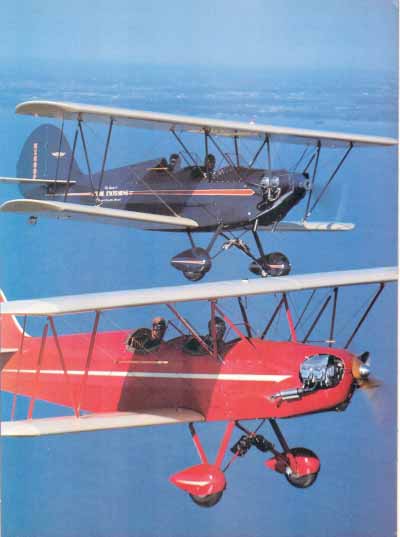

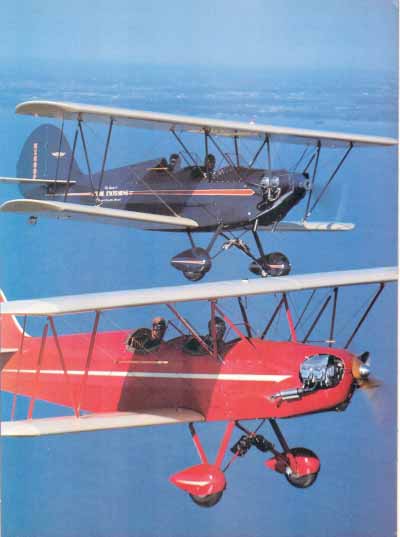

Now THAT looks like

fun. Two funky biplanes going somewhere together. |

When John Hatz, the FBO at Merrill, Wisconsin,

decided to design and build an airplane, he had no intention of offering

the plane for others to build. The project sat around in his shop

from 1959, when it was started, to 1967, when he finished the plane.

Hatz just wanted a fun machine and it was Dudley Kelly, an engineer

from Versailles, Kentucky, who talked him into allowing him to

draw up a set of plans and offer them to the public so they might

discover the fun of the Hatz. Unfortunately, John Hatz was killed

in an auto accident last year, but not before nearly 500 sets of

plans were sold and approximately 40 aircraft took to the air.

Frank states he found the plans to be excellent although they do

allow for a certain amount of personal innovation, such as the way

in which he crafted his own throttle arrangement — pivoted

at the top, like an amphibian, rather than at the bottom. Frank did

it that way because that's the way they had done it on their Pietenpol.

As designed, the airplane is supposed to utilize engines from the 100

horse 0-200 Continental up to the 150 horse 0-320 Lycoming,

meaning there is an obvious wide variation in weights. The plan weight

is supposed to be 850 pounds, although Frank says he has seen them

run from 820 pounds to as high as nearly 1100 bloated pounds. As

with all small airplanes, weight is the enemy of performance and handling

and most Hatz drivers report they are happier with the smaller engines

and lighter weight.

When it came time for Frank to select an engine, he found the cheapest

available to be a 115 hp 0-235 Lycoming out of a Pitts project a

friend had purchased. This is probably still one of the cheapest available,

mainly because of all the C-152s that have bitten the dust. Frank's

engine, however, is out of a 1947 Piper Cruiser. Once again, proximity

and convenience played the major role in supplying parts for a homebuilt.

Even though Frank is running a much heavier engine than the 0-200,

careful building and material selection, such as using the Stits

covering and finishing process, kept the weight down to within 20 pounds of

design weight. It's always satisfying for a builder to come that

close to the designer's original weight goal since the vast majority of homebuilts

far exceed what the designer had in mind.

Initially, Frank pointed me at the airplane and said, "go fly,

and have a good time:' A two-place airplane, however, should al-ways

be shown in its worst light: When carrying that extra passenger.

This is especially important with homebuilts, since so many of them

are actually excellent single-place machines but change their personality

entirely when the option to carry that extra person is exercised.

Frank Sr. was volunteered to be the guinea pig passenger who sat

in front, while I saddled up in the back.

In walking around the airplane, it's obvious no concessions were

made to modern times. With the framed windshield and exposed cylinders,

Frank has done an excellent job of capturing the 1930s in a 1990

airframe.

|

Can we say "simplicity" boys and girls? Visibility is excellent

in the air and on the ground considering the type. |

Climbing into the airplane was typical 1930s as

well. Wrapping a hand around the wires and then the centersection

hand hold was necessary to scramble over the gunwhales and down into

the cockpit. Frank has carried the nostalgia theme so evident on

the outside into the cockpit, where the polished mahogany instrument

panel worked with the rest of the cockpit layout to whisper lines

out of old black and white flying films. It was hard not to feel

like Noah Berry or Richard Arlen, as I pulled the helmet down and

fastened the chin strap.

After strapping in, I tested the controls and found the rudder to

be embedded in concrete with no movement available at all. I hadn't

noticed the tailwheel steering was direct, with no springs. Unless

the airplane was rolling, there was no way I was going to move the

rudder and the firmly attached tailwheel. I made a mental note to

expect quick acting steering and to limit my feet to exactly what

was needed and nothing more.

At first, wrapping my hand round the hanging throttle lever felt

a little strange but, since the actuating rod was attached to the

bottom end of the lever, it was very natural to rest a couple of

fingers on it and I didn't notice the situation even once after starting

the engine.

Turning the fuel lever by my right knee to the vertical "on" position

and hollering "off and closed;' I watched as Frank pulled the

Lyc through three or four blades before yelling "contact:' My

heels were firmly planted on the inward mounted heel brakes and I

flipped the mags to "both" as he swung the prop through.

This action was quickly followed by the sounds of a Lycoming happily

nibbling on the proper fuel/air mixture.

Since the tailwheel had no full swivel mode, I didn't know if it

would be possible to power up out of the grass parking spot and turn

90 degrees onto the taxiway. This question was answered immediately

as I put the left rudder down and the airplane smartly

executed a tight turn onto the taxiway centerline. Using the centerline

as a datum, I purposely made exaggerated "S" turns to get

a feel for the steering. As expected, I found it to be absolutely

immediate — whatever my feet asked the airplane to do, it did

instantaneously. Not many airplanes have such a direct steering mechanism,

so I paid special attention to how my feet felt and what my eyes

were seeing so I wouldn't be surprised on landing or takeoff by over

controlling.

I finished the rudimentary run-up and turned to look directly at

the temporary tower set up at Fond du Lac, reaching a hand over my

head to give them the thumbs-up. Just as quickly, they fired a green

light back at me and I taxied out on the centerline.

GO TO NEXT PAGE

|