Text and Photography by Budd Davisson

Air Progress, November 1976

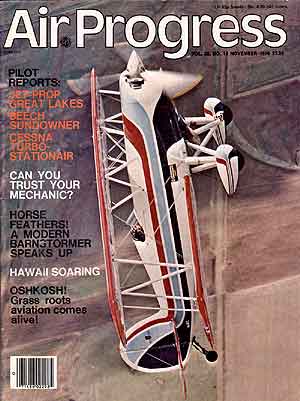

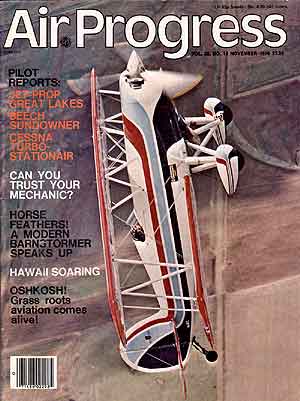

420 HP Turbine Powered Great Lakes....No, We're Not Kidding

Let's say you were a small manufacturer of specialty biplanes and you wanted to do something to really make folks yank their noses out of their salads and take notice. What would you do?

You could take it to airshows, but your airplane then winds up on the program sandwiched between a Goodyear demonstration of a blimp aerobatics (mostly ''bag overs") and the entire 300-plane airforce of Lower Freakystan doing formation loops.

A turtle slow, sort-of-lethargic, 180 horse biplane doesn't stand much chance of standing out in the boggled minds of the sun-scorched great unwashed pointing their bloodshot and totally uneducated eyes skyward. To make a real dent you'd have to do something really off the wall, like having Victor Buono as a wing rider . . . nude. However, since lifting that much heft (nude or otherwise) is out of the question, you have to look other places.

Since your piggy bank is stuffed full, you don't have to limit the places you search and sooner or later you wind up looking up the tailpipe of a turbine powered helicopter (well, it beats having a shoe fetish). "Ahah!" your totally unfettered (or is it unfrittered) mind exclaims. You have the answer: put a zillion horsepower turbine engine in your archaic little biplane, complete with reversible prop, and point your demo pilot at the sweet soaked crowd saying ''Go, boggle, or boogie, whichever comes first," and with a turbine powered biplane he is absolutely capable of doing both.

Of course, this is all fiction. Right? Wrong! This is the story of Doug Champlin, the subtle (but not very) owner of Great Lakes Aircraft and his willing-to-fly-anything pilot DwainTrenton.

Champlin is an easy-talking Okie with an oil family background and Trenton looks and drawls like somebody who, if he wasn't hustling around in some of Champlin's exotic hardware would be somewhere south of Macon, Georgia alternating between hustling booze in a super stock rum runner and charging the high banks of Daytona or Darlington. Together, Champlin and Trenton give the impression of being two good old boys having the time of their lives. And they are.

Champlin calls Enid, Oklahoma home (no telling what Enid calls him) and is undoubtedly the center of the wildest activity the town has seen since the days when Oklahoma crude was gushing down the streets with rye soaked bodies decorated with .45 caliber holes floating in it. Here, in three rather innocuous bigger-than -average metal hangars, is where Champlin quarters his world famous custom gun business, the final assembly and paint lines for his Great Lakes business and more warbirds than you are likely to find outside a museum. His Focke-Wulf 190D is the only soon-to-be-flying FW in the world, the same with his F2G "corncob" Corsair, his Daimler-engined Me-109 and his AD Skyraider. When Doug Champlin does something, he, as they say locally, flat gets it on.

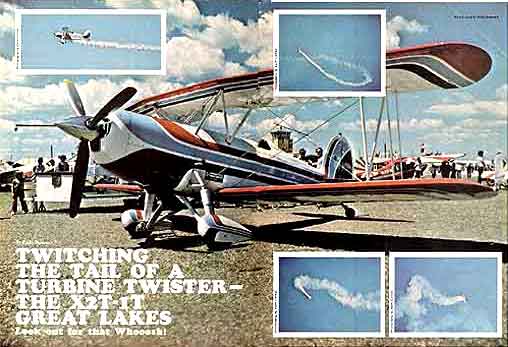

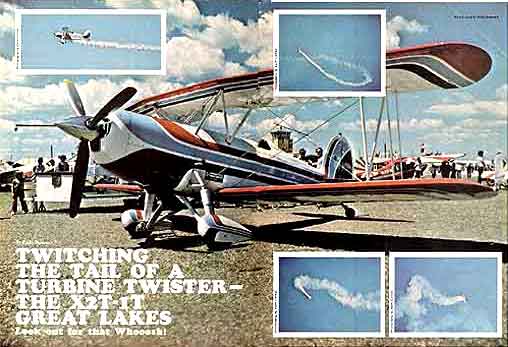

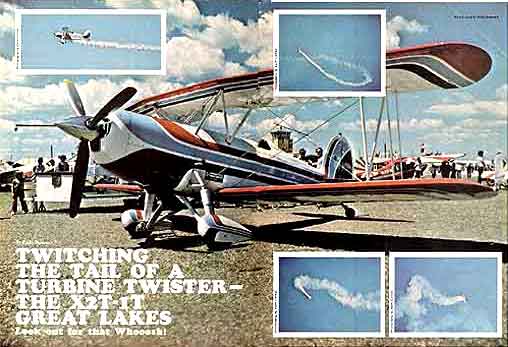

Only the three-blade prop and sewer-pipe exhaust gives it away. We shot this doing formation loops and Doug Champlin, who was flying me in the camera ship 'Lakes, had never done a loop before, so I was giving him dual instruction over the intercom while I shot the pictures. We did some "interesting" loops.

|

About a year and a half ago Champlin's biplane business was going but wasn't exactly taking off (pun intended) the way he wanted. So, somewhere in a bar after an airshow he andTrenton started a conversation centered around getting more performance out of their biplane. A Great Lakes has about the same drag coefficient as a tumbleweed so they knew that to make a visible improvement in the get-up-and-go of their airplane, they'd have to crowd an unreasonable amount of power ahead of the 'Lakes' firewall. They were talking numbers like 300 and 400 horsepower. Modern recips just don't give that kind of power without being the big eight cylinder flat jobs that Lycoming cranks out. Hanging one of those on the front of the Lakes would mean putting the rear two cylinders where the front pit is to maintain a workable CG and the front end would look like you were trying to cowl a mattress and box spring. The other reciprocating option would be something like an old 300 horse R-680 Lycoming radial or R-985 P&W with 450 hp, but both of these engines weigh almost as much as the airplane.

So, they reasoned, what has bunches of power but not much weight? Neither of them remembers who said it first (it was late), but when the word "turbine" found its way into the conversation and the gales of laughter died down, they knew they had found a way to get the attention they wanted. Who could come to an airshow and not remember the biplane with the turbine engine? The idea was so absolutely looney that it was beautiful!

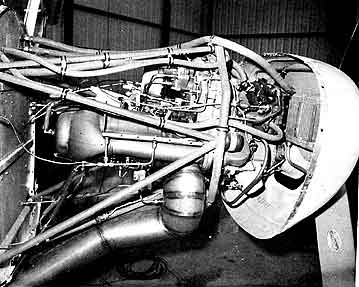

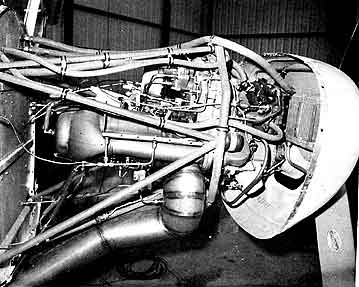

Of course not just anybody, good old boy or otherwise, could think in terms of turbine engines and wacky biplanes. An Allison 250 turbine sells for something like $60,000 and the propeller and other stuff boost it even higher. It's not a game for low buck daydreamers. But the results are fantastic, if a little unorthodox. The engine and installation weigh less than the original 180 hp Lycoming, even with everything but the pilot moved up in front of the firewall. So the turbine is located 8 inches further forward than on a stock ''Lakes," but few, if any notice the slightly longer snoot.

The entire installation is so carefully camouflaged that the idle looker isn't about to figure out what's cooking under the cowl. Only the three-blade prop and coal bin exhaust pipe are out of place and only the "Powered by Allison'' sticker spells out the exact nature of the boiler plant up front. The original passenger's compartment is now a fuel tank which gives the machine a total endurance of 2 hours or something around 325 miles. Other than these very minor changes, the Great Great Lakes looks just like the grandfatherly old number you find squishing down on runways in increasing numbers.

Enid, Oklahoma doesn't have a skunk works. Even so, Champlin cranked out his little kero-burner in almost perfect secrecy and sprung it on an unsuspecting world at Reading. He's not a talk-about-it-first type of individual. He does what he says he'll do before he says it . . . or something like that.

Anyway, after an afternoon of watching an almost stupefying number of almost identical airplanes doing identical things, the Reading crowd was truly ready for something different. Champlin and Trenton gave it to them. Trenton's show routine includes a max performance takeoff that has him disappearing vertically while doing a series of Immelmans and then reversing the prop to come screaming nearly vertically down to flare and touchdown in an area the size of a pup tent. All of these theatrics include the sight of a biplane coupled with the screaming sound track of a turbine-powered superthingie. It was about as different as staid old Reading is ever going to get. Whether it sold any airplanes is unknown, but it's a fact that every person who was thinking of plunking down some cash for a Great Lakes is now doing so with the rememberance of Trenton's zooming takeoff in the back of his mind. He knows all 'Lakes don't fly like that, but one of them does and that's enough.

If there was one question asked during the airplane's debut at Reading, it was a short "Why?" Champlin admitted to the show business aspect of bringing attention to his airplane but Doug Champlin doesn't do very many things just for the hell of it. If prodded further, he'd mention that he was looking at the foreign exhibition team market. Jordan's King Hussein, for instance,' just bought a herd of Pitts (or is it Pittae?) to put together a demo team called the Falcons. Just think what a country could do with something like the tubine 'Lakes which will do all maneuvers in a smaller box and will do really silly things between climbs and vertical descents besides? At an estimated $100,000 a copy it's a hell of a lot more expensive than a Pitts, but it sure beats funding a Phantom or A-4 for a season's fun and festivities.

The Allison 250 was shaft-rated to 420 horsepower for the 'Lakes and had a completely reversible prop.

|

I can't honestly say that I've thought a heck of a lot about flying anything Doug Champlin owns. Sometimes I've had hot flashes during the day that for an instant had me in his Corsair or something, but the more logical portion of my mind knows us raglegs don't get much of a chance at toys the caliber of Champlin's. So, when the phone rang and Doug asked me how I'd like to have first, and possibly the only, crack at this new Great Lakes, my wife had to revive me with a quick injection of Doctor Pepper(sugar-free, of course). I don't ever remember being as flattered as when Champlin extended that invitation. I also don't remember making travel plans as quickly, including convincing my wife that yes, it was a necessity that we visit my folks in Nebraska and we just had to see some old friends in Oklahoma City and Enid was on the way so . . .

I wish I had a book to use in setting the scene for the Great Turbine Freak-out. Doug's office is in one of those airport-standard steel hangars with absolutely nothing of any significance to be seen around it. As you open the door you find yourself in a small but impressively complete machine shop, again nothing of any real note unless you pick up on the tapered octagonal rifle barrel clutched tight by a milling machine's vice. Then, you step into the little lounge/lobby and there is plenty of significance. In the middle of the floor, for instance, is a (are you ready for this?) working .22 caliber Gatling gun and the racks on the walls hold hundreds of exquisitly engraved sporting rifles of the variety plebeians usually label "elephant guns.'' Lying haphazardly in a corner is a near-mint old Henry lever-action and another holds a tiny little Mannlicher pistol-carbine. The decorum of "nouveau ordnance" is laid over a basic background of walnut and good taste. The room is as much a den as a central lobby just off Champlin's office.

Then you step through a back door into his hangar and the real shocks begin. Yes, the turbine powered 'Lakes is there, but it's cowering under the towering gaze of an AD Skyraider (which gives you some idea of the hangar's size) and scrunched next to it are the ready-to-be-assembled components of the Focke Wulf with some Hispano engines for his not-yet-imported Dewoitine fighter. "Toyland, Toyland, Beautiful boys and . . ." The song I sing to my little boy kept playing through my mind.

My introduction to the megabuck biplane game was relatively simple and consisted mostly of Dwain Trenton spending an inordinate amount of time explaining the throttle quadrant to me so that I wouldn't absentmindedly find myself with a reversed prop when all I wanted was flight-idle. The throttle was three important positions, the "ground-idle" position has the prop at near feathered position with the gas generator in an idle position. "Flight idle" brings the prop back to its least thrust position and keeps the gas generator portion of the turbine at around 60% rpm. By lifting the throttle I could bring the prop back into ''Beta" or reversed position and the turbine would then spin-up to a predetermined amount of power.

Starting the crazy thing was almost as much fun as flying it. With Trenton's head hanging over one side of the cockpit and Champlin's over the other, I pushed both the ''Start" and ''Ignition" switches up together. The prop began to turn slowly and a high pitched whine built up. Then, as the rpm hit 15%, I advanced the mixture control and a very Phantom-like "whoom" told me things were burning up front and I watched the tailpipe temperature to be sure it didn't go out of limits. I turned the ignition and starter off and there I was, helmet and goggles, stick and rudder, four wings and lots of struts, and this turbine whining and kicking up a kerosene smell that made the whole thing seem like a bad LSD trip.

I beckoned Doug over for a final remark, him thinking I wanted some last advice, and I cupped my hand over his ear so I didn't have to scream when talking. I said, "This is the silliest damned airplane I've ever sat in. I love it!" And I was off.

As I was talking to the Enid tower and weaving my way out to the active I kept thinking of two things; 420 horsepower and $100,000. I looked down at my hands and noticed they were both sweating, especially the one around the throttle. Oh well, I told myself, it was 100 degrees in the sun. The sweat couldn't be nerves. No, it couldn't be nerves, even though I twice gave the call letters of the airplane to the tower backwards.

The cockpit of a Great Lakes is about the right size, not tight and fighter-like as in a Pitts or big with bathtub proportions like a Stearman or Waco. Also, the new 'Lakes now in production sit a little flatter than their predecessors so you have a fairly good view around the nose for takeoff. For this I was very glad because I was certain I was going to need to see all I could when I dropped the hammer on 420 horses in an airplane originally designed in 1929 for only 90 hp!

You don't see a lot of Great Lakes with torque meters and tail pipe temp gauges.

|

As I swung onto Enid's runway 17 I could swear I heard the tower snicker when it told me ''cleared for takeoff.'' Gently I began moving the condition lever forward and the 'Lakes just as gently, but a whole lot faster, started moving. Then, as the prop and the turbine section locked up, there was a sudden "whoosh," as if I had just gone into afterburner, and I was gone . . . flat gone! There was no screaming down the runway excitement of a fighter or a Pitts and no time to worry about torque or keeping the ball centered. There was no time for anything but to marvel at the way the ground seemed to suddenly get vacuumed out from under me by that magical little lever in my left hand. I was at least 50 feet in the air and climbing fast before it dawned on me to go ahead and put full power on it and bring the nose up.

As I was zipping upward, watching the altimeter wind up and keeping the rpm right at 100%, I said to myself ''This thing climbs fairly well.'' Then I looked at the airspeed and saw I was climbing at the bottom of the yellow arc, 120 mph IAS, when climb speed is something more like 75 mph! On that first takeoff, I never did get the climb speed down to 75 mph because I just couldn't force myself to pull the nose up that high.

Cloud base was 6,000 feet and I was ducking around in scattered cumulus faster then it takes you read about it. I had been cautioned by Trenton to keep the tailpipe temperature under 750 degrees and the rpm under 100%. With most turbines you run on percentage of rpm or torque pressure until a certain altitude and then you have to start runnng on EGT because the temperature gets too high. On most engines of this size that crossover occurs around 18,000 feet. The little Allison 250 is peculiar, possibly because it's meant for helicopters, in that it becomes temperature critical very low, in this particular case at about 2,500 feet. It's no big deal, you just have to use the temperature gauge to control the throttle instead of the torque meter or rpm gauge.

It would be no exaggeration to say that climbing at that rate with an engine that gives absolutely no vibration is akin to flying a bi-winged flying carpet. The wind noises past the wires and struts far surpassed the scream I knew the turbine must be making so the effect was one of a headlong rush upwards with no audible means of propulsion. Using the conveniently located stopwatch on the panel I found this elevator-like feeling was because I was climbing at 4,000 fpm, right up there with Bearcats and Learjets. The climb angle is so much greater than I'm used to that I was conscious of gravity trying to slide me backwards and pushing me against the seat back.

I couldn't get the nose level before the speed instantly leaped up to around 170 mph and even after bringing the power back to a cruise setting of 78 pounds on the torque meter I was still blasting along at 167 indicated. Once I leveled out on the top of a zoom of some sort at 8,000 feet and ran a cruise check and found it indicated 160 mph for a true of something like 190 mph. I would have given anything to sneak up on a Bonanza in that thing and pull up in formation with it. The Beech pilot would spend weeks having his engine gauges and airspeed checked and rechecked. It was a little unsettling to see that airspeed needle glued to 160-170 mph knowing the redline was 160 mph.

Who gives a fig how fast it is! The question is, ''Does it aerobat?'' and the unequivocal answer is "Boy, does it ever!'' The Great Lakes will never be a Pitts or a Stephens Akro, but then it's only about forty years older then either of those two, so if it goes through its maneuvers in a rather elderly fashion, it's to be understood. The controls are a little bit heavy (especially at 165 mph) and the roll rate isn't exactly lightning fast, but with that kind of power, it doesn't need to move fast to do its number. I unconsciously found myself bringing the nose up to the usual Great Lakes attitude when doing rolls and found myself gaining as much as 700-1000 feet per roll. Four point rolls could be dragged out so long that I could have had a sandwich while hesitating in knife edge positions and I could easily have out-climbed my Pitts while in an inverted position. All that power sure does make it a goer, if not a better akro machine.

Since I'm sort of a puny type I had trouble getting more than four Gs on it when doing loops or anything else going up. It really doesn't need that much G to make it over the top but I had the feeling I could have saved a little speed if I could have pulled the corners a little tighter. It was amazing to see how quickly the speed bled off even with 420 horses, so a higher G entry might have helped when doing vertical rolls and the like.

In general the feeling was like hustling around in a 420 horse parachute. The airplane's natural drag was exaggerated by the speeds I was running and the airframe wanted to slow down as badly as the engine wanted to keep going. What resulted was an aerial tug-of-war in which the winner was decided by my throttle hand. If I moved the condition, or throttle lever, at all the airspeed indicator would respond instantly. If I brought the power back significantly when in level flight, I was actually pushed forward into the belts. At the same time, it only took around 8 seconds to accelerate from 60 mph to 160 mph.

In playing with the throttle I discovered that turbine engines can do strange things. For instance, when I brought the power back to flight idle and the prop began to flatten out the airplane would slow down fairly quickly. Then, as the speed came down through 80 mph or so, it was as if somebody had reached out and grabbed my tailwheel. Suddenly, I had to force the nose down a sizable chunk to keep the speed from dying off all together and the rate of descent went out of sight.

Then, just for the hell of it, I brought it back into Ground Idle and let the prop flatten out completely. Boy, if you want to really scare yourself, that'll do it! The airplane damned near stops in mid-air. I nibbled at the Beta range a little bit but the way the airplane fell out of the sky each time I brought it past the detent scared me so much I couldn't force myself to 'leave it in Beta long enough for the turbine to spool up. Trenton says that spooled up in Beta the airplane comes down at something like 6,000 fpm!

About ten minutes into the first flight the chip indicator came on telling me the pick-up in the engine had gotten hold of some stray bits of metal. I got on the horn to the field and made a long straight-in scared to death I had broken Champlin's plaything. I could just see what was going to happen if I tried to put a $100,000 item in the miscellaneous column of my expense report. I was so hyped on the first landing that I didn't even notice what was happening until I was five feet off the ground feeling for the runway. I switched all my motor and speech functions onto a secondary circuit in my head while I worried about the engine. I was already swinging around in front of the hangar before I came to and smiled at Doug with a sheepish grin. Trenton came over, looked at the glowing light, said something to himself, then reached in and unscrewed the bulb while he muttered a vague sounding phrase about ". . . damned new engines, fuzz on the indicator . . ." I suddenly felt loads better.

This time I really enjoyed the takeoff. I dropped the hammer as fast as I dared and sucked the nose up into a steep attitude as soon as the gear left the ground. This time I had time to notice that there was absolutely no indication of torque on takeoff, something which amazed me considering the horsepower involved. Also, when I came back in for a landing the next time I took my time and experimented with things. The first time I had had some trouble maintaining a glide slope because I'd retard the throttle thinking I was high and the prop would flatter out and drop me like a stone. Then, I'd touch the throttle/condition level and the resulting surge from the turbine sections locking up would put me high again. The second time around I thought I had it wired. I knew it slowed down quickly so I came boiling down final at around 100 knowing it would drop to 80 the second I chopped the throttle. Since I couldn't see the end of the runway, I used the taxiway running left to right under my nose as an aiming point and played the power accordingly. At the last second, I edged the power back and set up for the intersection of the taxiway and runway I knew lay under my nose. Then I heard myself say something loud and obscene when the numbers on the runway popped up in front of me because that taxiway I'd been aiming at didn't intersect the runway. It crossed 100 yards off the end of it. Rooarr, surge, leap and I once again blew an otherwise perfect approach. As I settled back down into ground effect, this time over the runway, I bled the power back to idle and grinned a little as the airplane came to a near halt in the air (wind was gusting to 22 knots) and settled onto its squishy gear.

As I swung around in front of the hangar I brought the throttle back into Ground Idle and heard the familiar ''Aaarroow'' growl a turbine makes when the blades flatten out. Then I pulled the mixture and the delicious diminishing roar of a starving turbine came out from somewhere in front of my feet. They had warned me to stand on the brakes and keep the stick back when shutting it down, because when the prop transitions from flat pitch to feathered position the airplane tries to leap out from under you. It tried and I stopped it.

All I could say to Champlin was Thank you, again and again. I don't know exactly what will become of his project, whether any foreign governments or wealthy pilots will pony up enough bread to buy one of his machines or not, but I certainly don't look at his airplane with as much mirth as I did before. Okay, so the idea of a biplane/turbine combination is about a hundred feet past crazy, but it is one hell of a test bed to see exactly how the Allison 250 works out as a single engine turbine. At 30 gallons per hour, it's one of the most fuel economical turbines available, although at $60,000 apiece it's right in there with the rest as far as cost goes. The Great Lakes will allow the Allison to do all sorts of things in design and operation techniques that a regular airplane wouldn't allow because it would be operating too far outside its design envelope. The Lakes keeps the speeds down while still utilizing the power to its utmost. It's a good, albiet a little weird, laboratory for Allison.

Doug Champlin doesn't really seem to care too much what the other guy is doing. He just chugs along doing his own thing. I wonder if he realizes how much all the other guys are watching him though. We're all dying to know what he's going to do next.