GREAT LAKES

Text and Photography

by Budd Davisson

Air Progress, July, 1975

What price

nostalgia?

Oh, about $32,000

Remember when all there was to nostalgia was peering into a draft beer and remorsefully

reminiscing about the good ole days? Well, nostalgia isn't what it used to be.

Turn your back on your future, your present and your bank account- Today's brand

of remembering demands you go out and invest some long green in a few of the

stage props necessary for really hard-core day-dreaming. You have to put your

money where your mind is and support the new industry that offers instant nostalgia.

If, for instance, your daydreams cast you behind the wheel of a 1750 Alfa in

the 1933 Grand Prix de Nausea, you can buy replicas of everything from SSK Mercedes

to the Bugatti Royale. If firearms are your bag, you can spring for a Brown

Bess muzzle loader or a brand-new old 45-70 Springfield. But then, if you're

reading this, you must be an airplane freak, and you'll be happy to know you

haven't been left out. The aircraft industry, or more correctly, Doug Champlin's

little airplane company, is busy supplying us with a bit of nostalgia right

out of Waldo Pepperoni; the 1929-36 Great Lakes 2I-1A, trainer, akro bird and

nostalgia mount par excellence

.

It's not exactly hot news that the airplane is back in production What is news

is that a little more than a year after its introduction, the Great Lakes looks

like it is going to set aviation marketing theory back 45 years by actually

succeeding. Okay, so fifteen or twenty airplanes isn't exactly a biplane armada,

but by all current marketing standards, the Great Lakes anachronism should have

fallen on its stubby little backside. The airplane is slow, drafty and (oh,

my God!) acrobatic. But, then it's difficult to put a price on nostalgia. In

this case, though, the tab can run well over $30,000 a copy. (Ed’s

note: makes you want to cry doesn’t it?)

Unless you've lived your life in a monastery in the boonies of Nepal, you won't

have to be told that the Great Lakes 21-IA has long been considered one of the

best aerobatic biplanes ever produced by the American aircraft industry.  Designed

initially as a trainer in 1929, it first earned its spurs as a racer (honest!)

with a 90-hp Cirrus inline engine. Since running around inverted with your necktie

hanging in your face was considered a normal part of aviation in those days,

the akro hot shots discovered it and began raising hell in every corner of the

country. Although it makes my belly button want to run off and hide just thinking

about it, the Great Lakes, with Tex Rankin at the controls, holds the current

world record for consecutive outside loops: 131!

Designed

initially as a trainer in 1929, it first earned its spurs as a racer (honest!)

with a 90-hp Cirrus inline engine. Since running around inverted with your necktie

hanging in your face was considered a normal part of aviation in those days,

the akro hot shots discovered it and began raising hell in every corner of the

country. Although it makes my belly button want to run off and hide just thinking

about it, the Great Lakes, with Tex Rankin at the controls, holds the current

world record for consecutive outside loops: 131!

The Cirrus engine was junked by just about everybody who flew it and very few Great Lakes actually wore out their Cirrus (Cirrae?) before being re-engined with the beautiful little Warner radial of either 165-hp or 185hp. It's the pug-nosed little Warner-powered job that we all picture when the name Great Lakes pops up in conversation. My own mental image of the Lakes is of the gently smiling Harold Krier strapping into his Warner-powered four-aileron job and going out to set fire to the imagination of a whole generation of pilots

The last of approximately 450 2T-1As got their finishing coats of dope around

1936, the last survivors of what, were it not for the depression, might have

been the standard trainer of the thirties. Just before corporation executives

began taking swan dives out of fourth-story windows, the Great Lakes Aircraft

Company had orders on the books for hundreds of airplanes. It looked as if even

the sky wouldn't be the limit. After 1930, however, even massive sales and marketing

campaigns couldn't save them and they folded in 1936.

The type certificate expired and the manufacturing drawings and company name sat in a lawyer's file cabinet for nearly 30 years before Great Lakes freak, Harvey Swack. heard about them. After a battle with the Feds which would make a book in itself, Swack offered the plans for sale to homebuilders. Exactly how many were built isn't known. Swack sold his whole bushel of Great Lakes stuff, including the company name, to Doug Champlin of Enid, Oklahoma, and Champlin is the guy who set up the cookie cutters needed to reproduce the airplane.

Doug Champlin needs a little explaining, as he is probably one of the very few

people in the world who could pull off something as expensive and frustrating

as the resurrection of a long-dead biplane. Not only is Champlin in a "very

secure" position financially, but he's one of those renaissance types who

combine the lucky ingredients of ambition and infinite attention to detail with

a head for business and a real feel for things mechanical. In addition to cranking

out Great Lakes, he's one of the very foremost restorers of warbirds, which

includes an honest-to-God FW-190, and manufactures one of the finest lines of

custom sporting rifles in the world (Ed note: he has since sold that company

to his employees). In general, if he does it, he doesn't mess around.

I didn't have the

chance to visit either his Wichita manufacturing site nor the Enid, Oklahoma,

final assembly line, but I'm convinced they look more like a cross between an

operating room and Santa's workshop than a regular airframe line. The finished

product that I got to peek into, crawl under and eventually flop around in was

extremely well built and finely detailed, both inside and out. If you wanted

to pick nits, you could say the exterior finish wasn't as glossy as that on

some homebuilts, but I'll bet two dead mackerels that it'll last longer. It's

not one of those 24-coat wallpaper jobs that tends to crack and deteriorate

because it's so thick.

I didn't have the

chance to visit either his Wichita manufacturing site nor the Enid, Oklahoma,

final assembly line, but I'm convinced they look more like a cross between an

operating room and Santa's workshop than a regular airframe line. The finished

product that I got to peek into, crawl under and eventually flop around in was

extremely well built and finely detailed, both inside and out. If you wanted

to pick nits, you could say the exterior finish wasn't as glossy as that on

some homebuilts, but I'll bet two dead mackerels that it'll last longer. It's

not one of those 24-coat wallpaper jobs that tends to crack and deteriorate

because it's so thick.

Champlin is building two versions of the Great Lakes, a 140-hp version with

the original single ailerons (on the lower wing) and a beefed-up 180hp job with

constant-speed prop and the four-aileron mod that most airshow/competition pilots

made on the original airplanes. It was the four-aileron, 180-hp beauty that

Ed Mahler, the east coast dealer who's based at Sky Manor Airport in New Jersey,

let me borrow. Yep, it's the same Ed Mahler we've all seen doing the inverted

ribbon cut in his PJ-260 (now 290) and the solo routines on the Bede jet team.

Now he's content to be the eastern dealer for both Bede and Great Lakes and

fly nice "safe" airshows in his PJ.

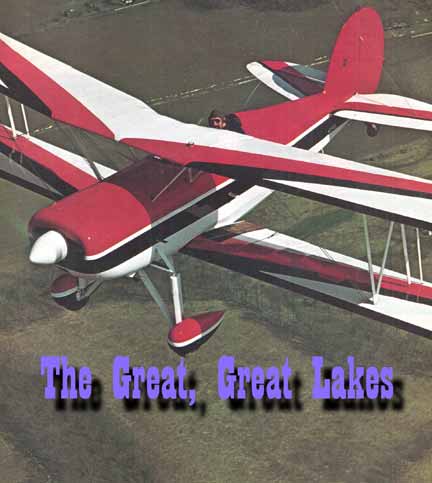

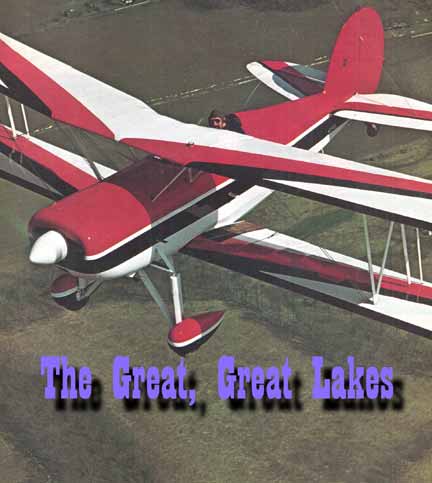

One picture is worth a whole bunch of words, and that's what's needed to describe

the appearance of the new Great Lakes. But, pictures lacking, the correct adjectives

would be something like medium-sized, stubby, tall, wide. The same set of words

would apply to any Great Lakes ever built because from the outside only the

engine, the extra ailerons and a taller tailwheel let on that it's a new airplane.

Even the wraparound windscreens, touted as a new addition to control cockpit

turbulence, can be seen in pictures of early racing Great Lakes, as well as

on Tex Rankin's aerobatic special. Internally the airplane is beefed up slightly

to better handle the bigger engine: denser spars, fatter fittings, thicker longerons,

and a few other little bits of added muscle.

Hanging a flat engine on an airplane designed for either an inline or a round

engine has traditionally been the quickest way to an ugly airplane. Somehow,

though, the fuel-injected 180 Lycoming and its cubic cowl seem to fit the Great

Lakes with a minimum of visual hassle. If anything, it looks much better then

it did with the original stubby little beak that housed the upright Cirrus boat

anchor.

Of course, the rest of the airplane is something right off a quick sketch on

a napkin in a 1929 diner. Its outrigger gear with the vertical oil/spring oleos,

the wide bathtub fuselage and the voluminous round tail all belong to long gone

days. It obviously shares an ancestry with its peer group of Travel Airs and

Wacos. My first thought as I peered into the cavernous cockpit, was that I'd

be rattling around like a marble in it. Then, as I dropped into the wide seat

and ran my feet up forward, I suddenly found my feet stopping much sooner than

I had expected. The seating and rudder pedal positions, as it turned out, were

the only things I really found at fault on the airplane.

We've become accustomed

to reclining seat angles with our legs out in front of us. If you don't believe

that, jump behind the wheel of a Model A Ford. Also, the average size of the

American male has increased a couple of inches in the past 40 years, which further

crowds cockpits and cars designed for a different generation. The final outcome

of this is that the cockpit of the Great Lakes, to me at least, made me feel

as if I was sitting on a picnic bench with my feet dangling down to rudder pedals

a couple inches too close.

We've become accustomed

to reclining seat angles with our legs out in front of us. If you don't believe

that, jump behind the wheel of a Model A Ford. Also, the average size of the

American male has increased a couple of inches in the past 40 years, which further

crowds cockpits and cars designed for a different generation. The final outcome

of this is that the cockpit of the Great Lakes, to me at least, made me feel

as if I was sitting on a picnic bench with my feet dangling down to rudder pedals

a couple inches too close.

Another holdover from the supposedly good old days is a trim system that even

Champlin says is due for modification. An eighth-inch nylon cord runs the entire

length of the fuselage along the left side of the cockpit. Grabbing the cord

and pulling it fore and aft cranks a screw jack up and down, which changes the

angle of incidence of the horizontal stabilizer. It works, but appears as Rube

Goldbergish as a curtain mechanism and is too slow for aerobatics. When you

go outside, you need to reel in about three feet of cord to get the elevator

pressures down. Champlin says they are working on a new system right now.

Taxiing down the narrow taxiway at Sky Manor made me conscious of how little

of the ground was visible around the nose. The tall tailwheel flattens out the

ground angle, which helps visibility a little, but the real problem is that

the fuselage is so wide that the cockpit coamings are in the way. By hanging

your head out the side, like the airmail types on the late movie, you can see

almost straight ahead.

The tailwheel ratio is just right and gives nice positive steering without extreme

sensitivity. This is a good thing, because the rear pit has heel brakes that

can be difficult to reach with a rudder completely depressed. This is made even

more difficult because the front seat pan interferes with your feet just enough

so that you have to concentrate at first to keep from catching a shoe on the

seat pan when reaching for a brake. Again, it's something you acclimate to very

quickly

.

It had been a long time since I had flown a bipe with as much wing as the Great

Lakes and I'd forgotten what it was like. There's no growling down the runway,

nose down, prop churning, feet dancing, waiting until the airspeed says you

have enough knots to go flying. You just punch the go-lever, hoist the tail

and the airplane picks itself up in around 500 feet at about 55-60 mph. It's

a very civilized maneuver, one that anyone- repeat anyone-can do with a minimum

of sweat. It's a whole different ball game and a rather delightful change for

those accustomed to rocketing down the centerline in Pitts or similar heavily

loaded biplanes.

During climb-out there is the subliminal feeling that here is one biplane that's

climbing on its wings and not the prop. It gently elevates itself, seeming not

to worry too much about how much headway it's making. At a climb speed of something

like 85 mph and a rate of climb approaching 1400 feet per minute, it's obvious

that it's going to go up at a pretty good angle.

The first flight was more for fun than evaluation, so for the second hop I tossed

my compadre and part-time boss (I instruct in his akro school whenever be can

find me), Fred Wilner, in the front seat, and we explored the airplane as a

couple of acrobatic flight instructors are bound to.

Sky Manor is right on the edge of a beautifully legal piece of acrobatic airspace

that's clear of airways and population so as soon as I could yank around in

a tight 180 while looking for traffic, I dropped the nose for speed. Nose up,

my hand automatically reached for the forward corner as we went around in a

positive "G" roll. Then a true slow roll, with my bead touching the

slipstream as I hung in my too-loose belts. Then it was Fred's turn.

While he was busy trying to churn my stomach with vertical rolls and such, I had time to notice how the cockpit felt when you weren't busy. For one thing, there is practically no wind at all running around in there with you. As a matter of fact, it's almost eerie, it's so calm, with only a tickle on the back of your head reminding you that you don't have a cabin over your head. There's none of the pit-to-pit tornado of airflow that so many biplanes have, where the downwash from the top wing bombards the rear pilot and roars toward and out the front hole. That's why, with the OAT at 24 degrees, the optional cockpit heater can keep the front pit at a toasty 82 degrees and the rear at 64.

I'd like to congratulate Charnplin for designing an intercom that actually works.

Even when making snide remarks to Fred while banging out in the wind, there

was no problem understanding. This alone makes any kind of training in the airplane

a breeze (pun intended).

My turn again, and I pulled into an inside rolling 360 (turning while rolling),

then a hammerhead. As I pivoted around at the top and saw the ground dead ahead

with the airspeed at practically zero, the thought occurred to me that this

was about as good a time as any, so I pushed. Or rather, I tried to push. The

controls up to that point bad moved with only moderate effort; neither heavy

nor light, about like a Decathalon but with much better response. But when I

pushed under into inverted recovery from the hammerhead, I found myself having

to put in a pretty healthy amount of shoulder to bend it around. Even carrying

nose down trim, outside maneuvers are almost two-handed affairs. I mentioned

that to Charnplin and it seems I am not alone in that particular complaint.

He's got elevator gap seals and servo labs right on the top of his list of things

to do.

When we took off it was only about 35 degrees on the ground, so there was no

way we were going to be warm at that height. But then after another maneuver

or two, I brought my bead inside the cockpit long enough to check the altimeter.

We had gained a couple thousand feet' Even with all the screwing around we were

doing, we were more than holding altitude. It's such a natural reaction to climb

between maneuvers that we were overcompensating. With a little careful attention

to speed and G-forces, the Great Lakes seems to bold its altitude as well as

even the lest competition birds.

But, alas, a competition bird it is not. But then it wasn't designed to be.

With its size and drag it is severely handicapped in vertical maneuvers, although

we had no trouble getting a clean half roll in that direction. To get a solid

full roll going up, you'd have to be light and right on, or above, the red-line

speed of 160 mph. Incidentally, the bottom of the yellow is 120, right at cruising,

so you do almost all your aerobatics well into the yellow. I had a tendency

to use more speed than the airplane needed. It performs fine at under 140 mph

and even pushes up oulside from the bottom at that speed with no sign of straining

.

Although Champlin didn't really say so, at least not for quoting, all of the

limiting numbers he has on his airplane appear to be extremely conservative

and aimed at the beginner. The placarded snap speed, for instance, is 80 mph,

which produces a slow, sloppy roll. Add 10 rnph and they become entirely different

maneuvers. Bang! It unloads and whips around, forcing you to gather your scattered

brain cells quickly to stop in level flight. One and a half snaps are actually

easier. I don't normally recommend working above the placarded speeds on airplanes,

but in this case it didn't add even a half G to the maneuver. As far as I'm

concerned, it made it safer because you've got much more control with which

to recover.

Although it lakes a bit of coaxing to make the airplane really do its best,

I couldn't find anything in its flight envelope that could not be handled by

even the rankest amateur, and that includes the landings. It's no fun to fly

an airplane you're afraid to land. That's why you see so many of the little

homebuilt biplanes for sale. They're fun to fly, but skip and skitter around

enough on landing that a lot of your life is spent planning excuses not to fly

the airplane. This can even be true of bigger jobs like the Stearman or some

Wacos. Not so the Great Lakes. With a normal approach speed of 75 mph, you waft

down final and simply squish onto the runway. The only problem a low-time pilot

is going to have is visibility. it's really blind on final and you’ll

have to either learn to slip down or get used to not seeing the runway until

you flare.

I had some real doubts about that spring/oleo landing gear until after the first

landing; then I tell in love with it. The spring cushions the landing and the

oleo damps the spring. What you end up with is a soft, almost squishy, gear

that has very little rebound. I came down out of a gust the first time and deserved

a good little bounce, but the Lakes settled down and stuck on like a glop of

whipped cream. The rollout was short and dead straight.

You hear the new Lakes compared constantly with the two-hole Pitts, which just

isn't fair to either airplane. They are different birds and appeal to different

people for different reasons. The Pitts' prime goal is to provide the best acrobatic

mount possible for two people, and that's exactly what it is, Nobody said it

was easy to land. The Great takes, though, was and is a trainer, first last

and always. It's an incredibly easy airplane to fly, but the compromise here

is the outer limit of its acrobatic capability. Personally, I prefer the Pitts.

But there are a hell of a lot of pilots who would have a fantastic time in the

Great Lakes who would learn to hate the Pitts very, very quickly. It depends

on what you're looking for, raw blazing performance or an airplane which offers

more fun than challenge and will still do far more aerobatics than 95 percent

of acrobatic pilots will ever learn to do.

It's not a cheap airplane and I don't think I'd recommend anything but the 180-hp,

four-aileron model, but then, nothing that's really fun today is cheap, especially

nostalgia. Look at it this way: you couldn't do a really first-class job of

restoring a Great Lakes (assuming you could find one) for less than $30,000,

and this gives you a brand new one with a lot less aggravation.

GREAT LAKES SPORT TRAINER 2T-1A-1

SPECIFICATIONS

Wingspan. ...............................26.7 ft

Length ..................................... 20.5 ft

Empty Weight (approx)......... 1140 Ib

Max Gross Weight ................. 1750 Ib

Wing Loading .................. 9.3 Ib/sq ft

Power Loading (140 hp)..12.5 Ib/hp

Fuel Capacity ........................... 26 gal

ENGINE

Lycoming 0-320-E2A, 140 hp

PERFORMANCE

Max speed (sea level) .........120 mph

Max cruise ........................... 110 mph

Max range (no reserve) .........300 sm

Service ceiling ..................... 12,400 ft

Climb rate (sea level, grossweight) .......... 1000 fpm

Takeoff (50 ft obstacle) ..........1006 ft

Landing (50 ft obstacle) ...........831 ft

(As we went to press, Great Lakes informed us that adjustable rudder pedals

will be standard equipment beginning in July. The new pedals will add three

inches of foot room, and are retrofittable to earlier models, even the

original antiques.-Ed.)