There are certain times when the spirit of an era seems to ooze out of the surroundings to drag one back into a period from whence they came. One could be standing amidst the ruins of an ancient culture or kneeling down to pull a rusty six-gun from the dirt where a retreating cavalry trooper dropped the weapon. Maybe it's simply sitting in the seat of a restored model T Ford or Duesenberg when the voices of another time come forward to tell stories of when that conveyance was new. It's often a feeling of wishful dejavu, wishing we could, for a split second, relive part of that era.

Such was the feeling that, swept over me as I glanced back over my shoulder, taking in the cabin of the Fairchild 45 and the living room appointments it contained. We were rumbling through space with the comfort and accommodations expected by sheiks and shahs, but they were from a different time - part of the definition of comfort, circa 1936.

Although there are lots of arguments about the exact beginning of aviation's Golden Age, most consider the period from 1930 to 1940 to be undoubtedly the single most productive ten-year period of aviation that didn't have a war to accelerate progress. Even so, the entire era is packed with contradictions. The United States had been pounded to its knees financially and was experiencing the worst depression ever seen. At the same time, the agricultural middle West was watching its topsoil become airborne and heading for the Canadian border. The longest, deepest drought on record forced tens of thousands of families into ramshackle cars and trucks holding all their belongings as they aimed themselves toward the promised land of California.

On one side, the United States was an absolute mess. On the other hand, aviation in every possible form was vibrant and alive and showing all the enthusiasm and eagerness characteristic of a pioneering market. It was as if the Cessnas and the Beeches and all the other legendary names didn't know it was impossible for them to succeed, given all the obstacles in their paths.

Perhaps it was the simplicity of the world combined with the simplicity of the machines that enabled many of the fledgling aircraft factories to come out with an entirely new model every few years. The number of variations staggers the mind as does the number of individual designs. They ranged from the Funks to the Taylorcrafts, and dozens of other names that were popping up. And then, of course, there was Fairchild, the Hagerstown, Maryland, manufacturer who produced so many different aircraft designs during the 1930s that were all aimed at satisfying specific needs of specific markets.

Many of these designs are currently little-known because they were aimed at such narrow markets and never did have very high profiles. One of Fairchild's specialties was working with bush operators in Canada and Alaska, which gave birth to such airplanes as the Model 71 and the Model 84, both of which mounted big radial engines on equally large airframes for operating on floats and skis. Their most popular machine was the legendary F-24 four-place personal transportation machine and the long line of primary trainers that reached into the war years to provide important aerial classrooms for the US Army Air Force.

And

then there was the Fairchild 45. The 45 is one of those airplanes

that had all the makings to become a legend in its own right -

similar to the Spartan Executive or even the Beech Staggerwing.

However, the 45 never made it in the marketplace and production

ceased after only 17 airplanes were completed.

And

then there was the Fairchild 45. The 45 is one of those airplanes

that had all the makings to become a legend in its own right -

similar to the Spartan Executive or even the Beech Staggerwing.

However, the 45 never made it in the marketplace and production

ceased after only 17 airplanes were completed.

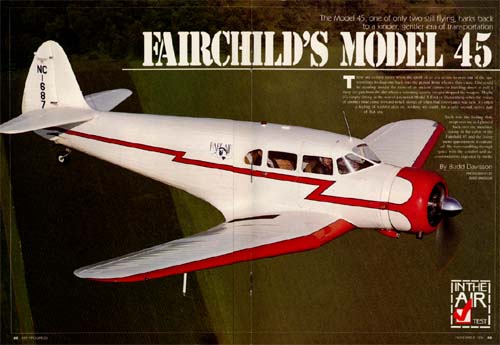

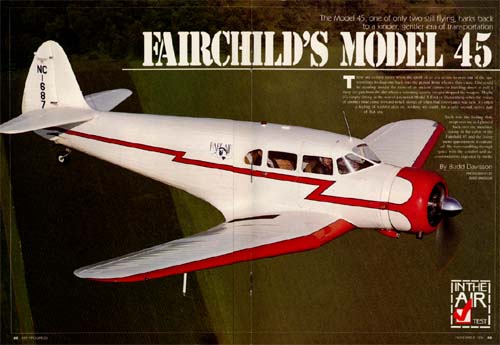

The Fairchild 45 was aimed at the growing mid-Depression executive transport market and addressed that market in exactly the same manner as the Stagger-wing/Executive - give the buyer comfort and speed. The Model 45 was, however, also designed to give them something else - incredibly easy and forgiving flight characteristics that would make it much easier for a businessman/owner to be his own chauffeur while the other two airplanes tended toward having professional pilots on board.

The small number of Model 45s produced went to the expected types of customers including a few oil companies, a few major manufacturing firms. and one actually went to the US Navy as a JK-1. Although their cavernous, five-place cabin and advertised cross-country speed of 170 mph (a gross exaggeration at best) were undoubtedly attractive, they were overshadowed by the more voluptuous Staggerwing and Executive. Also, the recognized safety of twin-engine airplanes let the Beech 18 and Lockheed 10/12 series ate up their market.

After the war, the surviving Model 45s flew on for a few years before becoming derelict curiosities at airports across the country. Today, even the more enthusiastic aircraft buffs are hard pressed to identify the airplane. The Fairchild is simply one of those designs that has slid into oblivion with so many others, including a goodly number of other Fairchild's.

At the present time, there are only two Model 45s still flying, with another one reportedly in pieces in a barn somewhere. Of those two, both have been re-engined with larger engines. The original 45 prototype had a 245 Jacobs engine which, considering the airplane's 40-foot wingspan and nearly 3000-pound gross, must have given a laughably anemic performance. All production 45's were equipped with a 330 horse Wright R-760 while the two flying have a Pratt & Whitney 450 and 420 horse Wright R-975 respectively.

One of the two flyers owes its survival to Bob Harbord of Sequim, Washington. Over an eight-year period, he rebuilt the airplane from a basket case. He had the Sorrells remanufacture the wing, while he did the fuselage and engine. Hanging the engine included getting an STC for the larger horsepower. The FAA even made him do a noise study!

Before being completely finished, the aircraft was purchased by Roger Dunham of Athol, Idaho, who operates Rare Air, Inc. Rare Air is a unique company that works with advertising and movie/video companies to utilize all sorts of vintage airplanes in an equally wide range of promotions. Their owned aircraft include a Waco YKS cabin and the Fairchild, both of which are used as much as possible for commercial, video and promotional activity. Any company seeking aircraft for use in any type of activity should consider giving Rare Air a call (208/683-3105, Hackney Airfield, Athol, ID 83801). Dunham is quick to point out that he received a lot of local help in finishing the machine, including Mitchell Aviation, also on Hackney Airfield, which pitched in and painted the plane.

Dunham brought his Fairchild 45 to Oshkosh '91 and undoubtedly wished he had made up a sign saying, "No, this is not an early Spartan Executive." So few people have actually laid eyes on one that almost no observers identified the plane as being a Fairchild.

With its graceful flowing lines and big round motor, the Model 45 has held a certain attraction for many of us who have also looked at that vintage aircraft as being perfectly acceptable transportation, even in today's environment. If you are doing 170 mph, you are doing 170 mph whether it's in a Staggerwing or a Cessna 210, a Fairchild 45 or a Mooney. Also, utilizing one of the older aircraft is infinitely more fun, if somewhat more aggravating, than any modern piece of sheet metal.

It was with this in mind that we approached Dunham with the typical hangdog expression that literally begs for a ride in an airplane you've always admired. We didn't need to look so mournful, since Dunham is probably one of the more enthusiastic aircraft owners we've ever met and has a zealous dedication to exposing people to what he considers a fine piece of aeronautical design.

There is almost no time during boarding the Model 45 in which any bending or contorting is done. Walking up the big metal center section and stepping into the cabin-sized door is exactly as if you were boarding an airliner. It's only when bending over to squeeze between the two front seats that your stand up stance has to be abandoned

As is my custom, I plopped into the right seat to give myself a right hand control/left hand throttle configuration and then discovered there were no brakes on the right. Roger said not to worry about that since the brakes were used only for stopping and very little for steering, except during taxi. Knowing how much Roger was in love with his airplane, my first thought was, "This was one very trusting soul to let a person into the right seat" - especially since the control yoke was of the throw-over type and he would have no way to get me out of an especially tight spot. Also, since I didn't have brakes I could conceivably compound the situation. I then realized his love of the airplane was not about to let him place it in any kind of jeopardy, and he knew something about the airplane I didn't - he knew the Model 45 was a pussycat.

Giving the radial

a shot or two of prime, Roger reached up and engaged the starter

and that lovely sound of a round motor coughing into life laughed

its way through the open side windows. I rested my hand upon the

top of the control yoke assembly and found it to be a very natural

position to work the vernier throttle while the windowsill was

exactly the right height to taxi along with my elbow hanging out

while hugging the yoke to my chest. Typical of the period, the

windows were crank-up, Hudson-style, safety plate windows which

make a tremendous amount of sense although they add a huge amount

of weight.

Giving the radial

a shot or two of prime, Roger reached up and engaged the starter

and that lovely sound of a round motor coughing into life laughed

its way through the open side windows. I rested my hand upon the

top of the control yoke assembly and found it to be a very natural

position to work the vernier throttle while the windowsill was

exactly the right height to taxi along with my elbow hanging out

while hugging the yoke to my chest. Typical of the period, the

windows were crank-up, Hudson-style, safety plate windows which

make a tremendous amount of sense although they add a huge amount

of weight.

Glancing around the panel, I located all the more important stuff, like the gear switch, the flap handle down between the passengers, and the tailwheel lockon the far side by Roger. Since we had a ten knot wind working crossways to the taxiway and the runway, I found the airplane wanted to weathervane despite the rudder's best efforts to keep it straight. I had to call for an occasional tap of right brake to keep it straight. At one point, I reached over and pushed the tailwheel lock into position and found it almost cancelled out the weathervaning characteristic. Sitting on the end of the taxiway, we waited until the temperatures came up and then performed the ritual mag and prop check. I glanced up to make sure I knew which direction the elevator and aileron trims turned and then taxied out onto the center line after the tower had given us clearance to take off.

Other than stating the 45 was essentially a pussycat and to fly the bird off slightly tail low, Dunham's flight instruction consisted of sitting with his arms folded and a slight grin. As I started the throttle forward and that thunderous Wright started doing its number, I hoped Dunham's confidence in both the airplane and the guest pilot had not been misplaced. With the amount of fuel we had on board we were still well below gross weight. Still, the airplane fed the horsepower out into the slip-stream and pushed us ahead at a speed that seemed leisurely but somehow in scale with the airplane's size.

Almost

as soon as it was rolling, I could feel pressure in the elevator,

so I gently brought the tail up into a near-level atitude - at

the same time doing my best to keep it straight down the center

line. I hadn't reckoned for the initial effect of the right crosswind

and was a little late getting corrective rudder in and we moved

a bit off center line. Fortunately, everything was happening at

a slow-motion pace - as if I was doing everything while stuck

in quicksand. The swerve was not deserving of its name since it

actually gently headed off to the right and then gently came back

on heading as I eased in rudder. While in a three-point position.

I had an excellent view of my side of the runway so there was

no problem seeing where I was going, even while tail-down. When

the tail came up, I could see every bit of the runway and had

no trouble figuring out where I was supposed to be. As the speed

worked its way up into the 50 to 60 mph category, the airspeed

needle position on the dial was telegraphed into the controls,

letting me know immediately when the airplane was light and ready

to fly. A gentle increase of back pressure (not a tug, just an

increase in pressure) and the airplane floated in the air at something

like 65 mph - and floated is the correct term.

Almost

as soon as it was rolling, I could feel pressure in the elevator,

so I gently brought the tail up into a near-level atitude - at

the same time doing my best to keep it straight down the center

line. I hadn't reckoned for the initial effect of the right crosswind

and was a little late getting corrective rudder in and we moved

a bit off center line. Fortunately, everything was happening at

a slow-motion pace - as if I was doing everything while stuck

in quicksand. The swerve was not deserving of its name since it

actually gently headed off to the right and then gently came back

on heading as I eased in rudder. While in a three-point position.

I had an excellent view of my side of the runway so there was

no problem seeing where I was going, even while tail-down. When

the tail came up, I could see every bit of the runway and had

no trouble figuring out where I was supposed to be. As the speed

worked its way up into the 50 to 60 mph category, the airspeed

needle position on the dial was telegraphed into the controls,

letting me know immediately when the airplane was light and ready

to fly. A gentle increase of back pressure (not a tug, just an

increase in pressure) and the airplane floated in the air at something

like 65 mph - and floated is the correct term.

I glanced out at the huge wing and noted the old cliche about the "wings filled with lift" was very true in this case since the fabric was visibly bulging outward between each rib, making it appear as if the wings were actually airfoil-shaped balloons. I toggled the gear switch up, letting the speed build to 95 mph and we headed out into the area to relive a bit of the 1930s.

As Wisconsin spread its checkered landscape out to the horizon, it was very easy to imagine our tweed double-breasted business suits on hangers in the back as we loosened our bowties and continued on a business trip which would take us to some fledgling industry somewhere else in the state. The big cockpit with its multi-faceted windshield hinted at what it must have been like to be corporate executives in the pre-Learjet days when a 150 or 160 mph cruise speed was on a par with the airlines and far outstripped the overnight passenger trains that still formed the mainstay for business transportation.

As I pushed over into level flight, the nose kept coming down until the top of the cowling became nothing more than a minor reference as it dropped out of our field of vision. Only the wide framing and the windshield broke up the scenery',' - and even that ceased to exist visually after a few minutes. Carefully trimming out the elevator pressure, I watched as the airspeed did its best to work its way around to 125 mph indicated (far short of the 170 promised in some of the factory literature), but then we were still quite low. One advantage of big motors on big airframes is that altitude is a friend. Even the factory literature showed a 15 mph increase in cruise speed between 2000 and 8000 feet, an altitude we weren't about to reach unless we decided to go IFR for the last 3000 feet.

With wings the size of tennis courts, I didn't expect the Model 45 to have the roll rate of a Pitts. I was pleasantly surprised to find the control pressures and breakout forces to be nicely balanced. I was even further surprised to find the airplane had little or no adverse yaw. With wings that long and fat and the period which gave birth to it, the airplane had every right to fly sideways, when the aileron was hung out with no compensating rudder. Even hard aileron deflection with no rudder produced only the mildest amount of adverse yaw. In pitch, once it was trimmed up. it was almost perfectly neutral in that if you pushed the nose down. it stayed down and if you pulled the nose up, it stayed up. This is no big deal unless you are trying to fly hard IFR in severe turbulence. This was not likely to be the case with this grand old lady.

I got the carb heat and power back and brought the nose up waiting for the needle to work its way into the low 50s before, with a brief shudder, the airplane unloaded and asked me rather impatiently to let go of the stick so it could begin flying again. Although the break had only a slight edge to it, it stayed stalled and settled for a second or two even after releasing the back pressure, but the slightest bit of power immediately put it back over the bubble and into the air. Partial flaps only accentuated the characteristics while bringing the speed down a mile or two. I had no interest in doing the same drill with full flaps since the broad centersection flap that ran all the way across the fuselage bottom undoubtedly did weird things to the tail and took copious amounts of power to overcome its drag. We were only at 2000 feet, so for once I decided to do the prudent thing and head on back to the airport and land, rather than trying more serious stalls.

Coming around on downwind, I toggled the gear down and grabbed one notch of flaps, telling Roger I had no intention of pulling any more than one notch. I figured the more flap I had, the more critical round-out to touchdown would be and there was enough of a crosswind, I felt I might have my hands full anyway. Having no idea how far the airplane would glide, I carried it out a Cessna-like distance before turning base to give myself plenty of room. Even so, I still found myself just a little higher than I wanted to be. Roger said the best approach speed was 65-70 mph, but as I got it down to 75 I began to feel as if the slow motion thing was happening again and I had a difficult time getting it under 70.

With only one notch of flaps, the nose was down, giving tremendous visibility, and I can't imagine what it must be like with more flap. Using the center line as a guide, I waited until we were reasonably low before I began bringing the nose up, anticipating a high-speed burn-off during the flair. As it turns out, with only one notch of flaps, the speed burn-off wasn't as high as anticipated and I floated a bit, which gave me plenty of time to get set up. I squeezed in just a touch of power before the right main touched, and then glued both of them on. Considering I am not used to sitting that high in the air, I would have to say the airplane compensated for what could have been a real bouncy landing, because I touched down about a foot before I expected to. The big, soft doughnut tires and long, squishy landing gear absorbed all the shock, letting the airplane flow onto the runway like a slow-speed cream puff.

As soon as we were on the ground and rolling out, I told Roger that when I let the tail down the airplane was his because he had the brakes. As it happens, I should have probably dropped the tail a little earlier than I did to make it easier to counteract the crosswind. This was still no problem since, again, everything was happening in slow motion. As soon as the tail came down, Roger got on the brakes and we unlocked the tailwheel to turn off onto the taxiway.

This is a flight I had been looking forward to for a long, long time - ever since the Fairchild 45 first peeked at me from the pages of one of Bill Green's old reference books. The 45 has always been one of those airplanes I thought would be a great piece of personal transportation. Was I disappointed? Maybe a little in that the speeds weren't as high as I had hoped, but that was more than compensated for by the overly genteel nature of the airplane. This machine doesn't appear to have a mean molecule in its makeup and is one of the easiest, most pleasant-flying airplanes of its type and deserves to be better recognized.

Looking back, the only reason the 45 was not better accepted by the marketplace was that it was so thoroughly outperformed by the competition. However, that may not be the entire story, since this airplane's speed is being reduced by 55 years of age and Roger says he quite routinely flight plans 150 mph and almost always gets it. Whatever the reason, the Fairchild 45 is a totally unique piece of aeronautical history that offers a wonderfully nostalgic glimpse into a time where comfort and appointments were more important than cost and speed.

Roger Dunham's company is well named. The Fairchild 45 does have a rare air about it!

BD