An editorial comment: Where Have All the Pireps Gone?

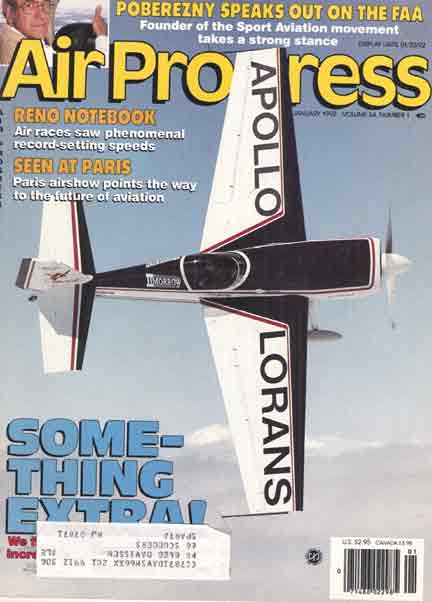

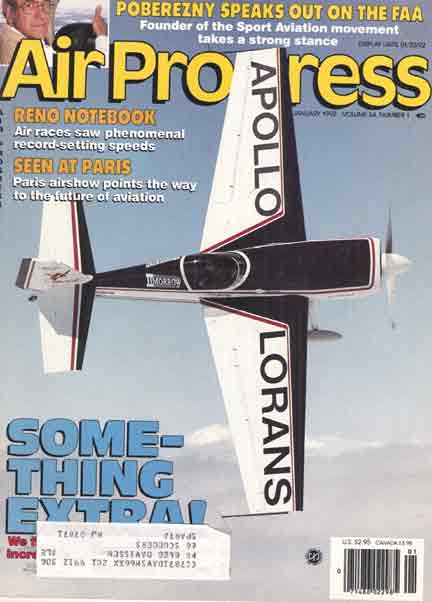

I hope you don't mind a personal observation, but when I laid this issue on

the scanner, as is usually the case, the magazine brought forth lots of memories

attached to it. First, of course, was getting to fly my good friend Patty Wagstaff's

airplane. The second thought, however, is that the above is the last cover I

shot for Air Progress. After 25 years and over 200 covers, we parted ways, and

a few months later, they closed their doors. No, my leaving had nothing to do

with their eventual demise. It was the publishing business that cut its throat.

As I look at that cover I can't help but think how things have changed over

the years. All the time I spent working with Air Progress, I knew if I ran across

an interesting or exciting airplane, I could be guaranteed that they'd want

the story. Today, I wouldn't know where to go with an article like this. There

are no magazines running pilot reports on unusual airplanes. Oh sure, you can

see all the Cessna/Piper/Beech reports you want, but none of the Walter Mitty

type stuff that we did so much of in Air Progress.

Our theory was that lots of pilots and enthusiasts want to know how the different airplanes fly, so for nearly three decades we gave them what they wanted. I did 250-300 pilot reports from 1968 to 2004. The last magazine that was interested in antique/homebuilt/warbird pilot reports was EAA's Sport Aviation, but now even they don't want them. So, that's what Airbum.com is all about: flying airplanes (and a bunch of other neat sh*t). If you're reading this, I appreciate your coming onboard and proving that people still like to ride along and see what it's like to fly neat flying machines.

Incidentally, I'm trying something new on this pirep. I'll keep the photos

fairly small so the file loads quickly, but I'll link the small photos, so you

can click on it and get a bigger view. Incidentally, don't forget that these

are scans out of magazines, so may not be as sharp as what you're used to seeing.

SOMETHING

EXTRA! We

fly Patty Wagstaff's mind-bending Extra 260 By

Budd Davisson

The

two transparent tubes down by my right knee showed exactly how much

fuel was in the main tank and the auxiliary acrobatic tank. Frowning,

I sighed with frustration, I thought, "Dammit, I'm going to have

to take it back to her because there isn't enough fuel to get so far

away she won't be able to track me down." In

the worst way, I did not want to give the Extra 260 back to Patty Wagstaff,

who was patiently -- and probably anxiously --- waiting for me back

at Blairstown Airport. Patty had turned me loose to frolic in her

one-of-a-kind Sukhoi Killer, and I had fallen madly in love with this

unbelievable acrobatic hot rod.

Most

of the airshow-going world by this time at least knows what an Extra

300 looks like, courtesy of Clint McHenry. He acrobats the hell out

of that two-place bigger brother of Wagstaff s 260. Some of the more

acrobatically enthusiastic might even know the Fxtra 230, the 200 horse

single -place Extra often mistakingly thought of

as a Laser clone --- which it definitely isn't. Patty's

airplane is the best of the two. It's basically the smaller airplane with a modified wing and 300 hp engine.

The aircraft is, however, the only one in the States and, therefore,

something of a secret - or at least it was until the 1991 airshow and

competition season. By

the time you are reading this, any aerobatic enthusiast will have already

seen Wagstaffs throttle-to-the-wall, floor-to-ceiling hyperkinetic

aerobatic show. When I strapped on Patty's airplane, the craft was still

new to the circuit and I wasn't certain what to expect, and, had I seen

even one of her shows, I would have known I was in for the ride of my

life. As it was, I was treated to the delightful experience of self-discovery

and was allowed to saddle up the best behaved, highest-spirited

thoroughbred in the stable and told simply to go play. And I did! Those

who have not seen Patty's show are going to be first impressed

by the show with its rudely artistic geometry and the razor-like precision.

Secondly, they will be taken aback when Patty opens the canopy and steps

out. The image of the flight and the image of the young lady seem at

odds. Where the show is frenetic and nearly brutal, the pilot is

a pretty and petite lady with none of the visible savagery she demonstrates

in the air. Patty is also only seen by her public after she's been standing

out on the ramp for several hours. This, of course, always ensures the

appropriate airshow look - sunburned, windblown and tired. Patty appears

to be an interesting contradiction: On the one hand, there is an initial

almost-shyness which fades to a broad smile once the ice is broken.

Once strapped in, however, the tigress comes out to play.

When

asked where she was born and raised, she flashes that million-dollar

smile, which some smart advertising agency ought to pick up on, and

says, "nowhere and everywhere." She is referring to her background

as an Air Force brat moving from location to location around the world,

but she admits if she feels homesick, it is for Japan where she spent

her high school years while her father was flying in the Air Force. Patty's initial in-cockpit aviation experience was on her father's lap at the controls of a B-25 (we're not going to ask how that came about, but a base commander somewhere is scratching his head). She then lived around the edges of aviation since everyone in her family is involved one way or another. She didn't actually start to learn to fly until she married Bob Wagstaff. The two of them were probably drawn together by their mutual interest in living life a bit differently than most. Bob

was originally a lawyer in Kansas City who decided it was time for a

change, so he moved about as far out of the state as he could to set

up practice - Anchorage, Alaska. Already a pilot, he encouraged Patty

to learn to fly and she, with her lifetime's immersion in the industry,

moved quickly through the ratings to become an instructor in the Anchorage

area. She came into flying competitive aerobatics in 1984 when she flew

her first airplane, a Decathlon, all the way down to Fond du Lac, Wisconsin.

This was not only her first competition, but the first time she had

even seen an aerobatic box. The Decathlon was quickly replaced by a

Pitts S-1S and then an S-1T - the final single place variant in the

butt-kicking, round-wing Pitts tribe. As the Unlimited class become

more and more dominated by monoplanes (specifically the Laser 200

variations), she looked around and latched onto the Extra 230 as the

logical hardware to beat the Lasers. By this time, she was doing battle

with the best pilots in the world and qualified for the World's

Team in 1985. By the time she qualified

for the World Team, she had been flying contests only one year and had

not yet won the nationals. She has received her share of awards, including

both the Betty Skelton and Rolly Cole awards but, in 1991, she won the

most important award when she was the overall winner of the national

contest. It's important to understand she didn't win the women's

division, which doesn't exist. She won all the marbles. She beat

them all–men and women both– to become national champ. Possibly

the best indication of Patty's attitude toward life in general

and competition in particular is the placard in the middle

of her instrument panel which states "Kick Ass:" She doesn't

like being second. And she doesn't like flying airplanes that are anything

but the very best. She's willing to pay the price required to be

the best and fly the best. The price is not only goodsized sums

of cash, but a grotesque amount of time. Although

many who had flown her original Extra 230 considered it to be one of

the best balanced acrobatic airplanes in the world, Patty had seen the

Sukhois fly and knew she was going to need something with more performance

and lots more power for increased vertical performance. By this

time, Walter Extra was flying the six-cylinder Lycoming IO-540-powered

260 as his own personal acrobatic mount in contests in Germany,

and Patty saw the plane had definite potential to do some serious butt-kicking. Beginning

in 1990 and working through Brian Becker at Pompano Air Center in Fort

Lauderdale, Florida, negotiations were begun and the airplane changed

its citizenry and received a few modifications along the way.

Acrobatic specials like the 260 are never actually finished. After receiving the airplane and having a flutter test performed by Carl Pascarell, she moved the airplane to her winter base at Tucson, Arizona, where she spends at least half of the year, most of it either practicing or tinkering with her airplanes. There, the airplane received a few more refinements before hitting the airshow, trail at the beginning of the 1991 season. And then we pick up the story at the point where I was trying to figure out the best way to steal her airplane. To

picture the scenario, you first have to adjust to a few basic numbers

and then try to picture the cockpit. Here is an airplane with a 26-foot

wing, over 300 horsepower, yet only weighs 1150 pounds. All that horsepower

is fed out into the slipstream by a three-blade composite MT constant-speed

prop. The airplane carries a total of 45 gallons of fuel, 10.5 of it

in the header tank that has the flop tube and is the only tank used

for serious aerobatics. The

instrument panel is, as would be expected, as well instrumented

as an akro bird can be, which is to say there isn't much. Although the

weight of avionics hurts the airplane in competition, it certainly makes

life a lot easier on cross-countries, which is where it spends most

of its time. Fortunately, Patty is sponsored by II Morrow,

the world's leading manufacturer of lorans (Ed note: Wow! Remember

those?), so the craft has the top-of-the-line loran. When

I saddled the airplane up on the ground, I was vaguely bothered by the

unusual tubing structure that crosses the cockpit over the top of the

control stick. The tubing is there to beef up the cockpit area, which

is always a weak spot in any acrobatic airplane. Unfortunately, it seems

to separate the pilot from the instrument panel and I was constantly

reaching over or under to get at something. Given the choice of easy

mag switch access or a strong fuselage, I'd pick the fuselage option

every time. At 6,000 feet on a crystal blue spring day, absolutely

none of the foregoing made any difference. The only thing that counted

was the way this airplane felt and flew. And boy, does it fly! Among

other things, at that altitude and 23 square, I was indicating

190 miles per hour! Patty says she flight plans 190 knots cross-country

and almost always gets it. With performance like that, airshows suddenly

seem much closer. On

the short trip out to the aerobatic area, I was already in serious "like"

with the airplane, if not out-and-out in love, simply because of

the airplane's control harmony. The ailerons are very quick to

respond, meaning the second the ailerons were deflected the airplane

immediately gave me the roll rate that amount of stick deflection called

for. All that response and roll acceleration was at the expense of reasonable

breakout forces. With the stick in neutral, there was no tendency to

overcontrol or to search from one side to the other because there

is a clearly defined "notch" in stick pressures to indicate

when passing through neutral. Everything

about the airplane, from its fishbowl visibility (if you don't count

not being able to see down to the sides because of the enormous wing),

its unbelievable climb rate (which easily tops 3500 feet per minute

if you want to push), and its comfortable, only slightly supine

seating position, makes you glad to be in the cockpit. Going somewhere

isn't what the Extra 260 is all about - staying in one tight little

space and jamming it full of maneuvers is the Extra's mission in life.

As

I pushed over into level flight in the akro area, the air was so clear

I was conscious of being able to see about a trillion miles. I had to

take my eyes off the not-so-far-away skyline of New York City and mind

the business of flying someone else's mega-buck airplane. Initially,

that meant making certain I had burned off enough fuel in the rear main

tanks to get the CG into limits, before switching over to the aux tank.

With the main tanks so far back, the airplane can be CG critical, so

akro isn't attempted until the main tank is down to a given level. On

the way out to the area, I was so busy loving so many aspects of the

airplane that I had no pre-disposed plan of action. I was absolutely

positive it would be a waste of time to initially do something mundane

like a loop or an aileron roll. I yanked the nose around in two screaming,

clearing turns before pushing down to get speed for a vertical

roll. I was certain a vertical in this airplane was going to be

a serious experience. What I didn't know was that even my wildest

imagination was going to fall short. The

vertical roll gave me the two biggest surprises of the entire flight.

When I began the pull, I had no idea how much stick pressure was going

to be needed to pull a relatively tight arch, so I gingerly started

back on the stick. Immediately, I wasn't pulling tight enough, so I

gradually increased the stick pressure. As fast as the thought can flicker

across your mind, I had 7 Gs nailed on the airplane without trying.

At exactly the same point that I was beginning to increase the

back pressure, the stick force actually got lighter and it became easier

to pull G. In other words, the stick force gradient is not linear -

it falls off as the G-load goes up, making it ridiculously easy to inadvertently

hammer a lot of Gs on the airplane, which I did. I was looking for 5-1/2

to 6 and would up with a shade over 7. The

airplane established the vertical with almost no help from me. Watching

the attitude indicators out on the wings, I lined them up with the horizon

and slammed in the left aileron to see if I could make that wingtip

track the horizon, which on this particular day was a clearly defined

line out about 50 miles. Surprise number two! I

actually heard myself say, "Holy S---!" out loud, I was so

surprised. Up to that point, I had only used normal aileron displacements

in doing 70- and 80-degree banked turns. When I put the aileron against

my leg, or at least tried to, the airplane ripped around so quickly

and with such instant response, that the inertia of my hand actually

caused the stick to come off the leg and back toward neutral, slowing

the roll rate noticeably. Roll acceleration was so high, a full deflection

roll was almost violent. Instinctively,

I put aileron back in and could not believe how easily the airplane

changed roll rate while still going straight up. Long before I was expecting

it, my reference point showed and I had to get the stick back in

the center or I was going to go ripping past the point. While still

laying on my back and pointing straight up, I glanced down at the

airspeed while waiting for the airplane to slow down. Then I waited,

and waited - and then waited some more before pounding on the left rudder

for a not particularly competition-quality hammerhead. As soon as the

nose was down, I went for more speed - I wanted to do some more of those

verticals and play with that wildly controllable roll rate. This

time while I was in the vertical I could see a little more of what was

happening. It was positively amusing to start at a slow roll rate,

then jack up to an unbelievable rate, stop it, roll in the other direction,

do point rolls, and in general enjoy control on the vertical like I

have never experienced before. I thought I was just being wonderfully

adroit at the controls, but looking back after I was back on the ground,

I realized the airplane was so well balanced it quickly allowed me to

figure out what was going on and catch up with this amazing roll performance.

I wasn't such a wonderful pilot; it was just that the Extra 260 was

so user-friendly. I

can't even begin to retell what happened during the next 40 minutes,

since it all tends to blur together in a G-induced haze. Individual

memories, which produce akro-giggles still project into my mind. For

instance, at one point I decided to snap roll the airplane. I slowed

to what seemed to be a reasonable speed (about 120 knots) and used conventional

snap techniques. The airplane obediently broke, whizzed around

and then immediately stopped when it came back level again for what

was one of the easier to control snaps I'd ever done. The unusual

feature was that throughout the entire maneuver the nose didn't pitch

up three or four degrees. Immediately

after coming out of the snap roll, I let the Extra accelerate for a

second before doing a full deflection, nose-on-the-horizon slow roll

and realized from my perspective it was very difficult to tell one from

the other because the nose attitudes and roll rates are similar. Judges

must have a terrible time telling a slow roll from a snap! One

interesting and consistent pilot induced glitch I couldn't cure

was that on every outside loop I did, whether from the top or the bottom,

I'd gain about 20 degrees of heading. I never did exactly figure out

what I was doing wrong. There was either too much or not enough rudder,

but I am going to have to play more to figure it out. The

airplane ignores gravity and doesn't seem to care where the nose is

in rolling maneuvers, so one of my other problems was keeping from aerobaticing

right up into controlled airspace. I'm so used to bringing the

nose up slightly to do many maneuvers that I would start out at

4000 feet and then suddenly be at 8000 feet.

After

about 20 minutes, I found I wasn't paying any attention to whether I

was going up or down, since any amount of speed combined with full

power allowed me to do any maneuver. I got a huge kick out of being

dead level, with the nose on the horizon and shoving the throttle to

the stop. I'd wait a second until it was passing through 200 mph, flip

the Extra on its back without even bothering to bring the nose up and

then push it up into a vertical roll. Then I'd let the plane hang there

for a while before pulling off the top to fly away inverted When

making our arrangements to get together, Patty and I had had some discussion

on how big a runway she needed for the Extra and she said narrow runways

are a problem because of visibility. Knowing I was going to have to

fly the airplane, I offered to meet her over at Blairstown which was

a 70-foot-wide runway. This is 20 feet wider than our home field and

doesn't have landing lights sticking up like a picket fence along the

sides. Even as I was strapping the airplane on, I know that had been

a wise decision, and the more I flew the airplane the wiser the decision

became. Sitting on the ground, the visibility around the nose is about

as good as you get with most tailwheel airplanes. That's not the problem.

The problem is the wing. The pilot sits so far back in the fuselage

that the leading edge of the wing effectively blocks off all but a fairly

small amount of the runway. And this is something that was in the

back of my mind as I begrudgingly brought the power back and headed

back toward the airport. Patty

was new enough to the airplane that she was still working out her landing

techniques and gave me a couple of basic guidelines, including fly short

final at 100 mph and carry just a little bit of power into the flare.

Since neither one of us knew if that was absolutely correct or not,

as I came on a downwind I opted to fly an approach not unlike I would

in a Pitts, which includes a power-off, turning approach. As I bent

around and came down to the centerline, it became obvious the 70-foot-wide

runway was about as narrow as I would be comfortable with until

getting more time in the airplane because the smallest bit of runway

was visible ahead of either wing. And then I started trying to guess

where the ground was. I

had plenty of time to worry about the general location of the ground

because the airplane floated like a T-Craft and just didn't want to

come down. When it finally did come down, it was with an unceremonious

thump, as all three gear found the runway at the same time. I

let the Extra roll a little while and satisfied myself that it

was at least as stable on roll-out as a Citabria before dropping the

hammer to go around. I wasn't particularly happy with the landing

and I was also farther down the runway than I wanted to be. On

the next two approaches I tried slower speeds with just a little

bit of power in the flare and

they bordered on the ridiculous since the airplane wanted to stay up

like a glider with the spoilers in. On both of those, I touched the

ground just briefly to let the airport know I had been there, then dropped

the hammer to come around in a

fourth approach that was more like the first, only slower. This

one worked out much better and, although the touchdown wasn't superslick,

it was still straight with no bounce. Once

on the pavement, the landing is anticlimactic since the Extra rolls

absolutely straight ahead and decelerates beautifully. I

found in the air that the airplane stalled somewhere in the low 60s,

which means I was approaching way, way too fast. I would like to go

out and spend an afternoon playing with the airplane to see if

I didn't feel better flying in a steeper, slipping approach at a slower

speed. Patty says now that she's been flying the airplane for nearly

a year she brings it in much slower than she did at the beginning. At

this point, I have to begrudgingly admit that I'm one of the few

aerobatic pilots in America who hasn't flown the highly touted Sukhoi

Su-26M, so I can't give a direct comparison. Practically everybody I

know has flown the Russian craft and they have said the same thing:

The Sukhoi really performs but requires a lot of technique to fly

well. So even though it may outperform the Extra 260, it takes

much longer to feel at home in the cockpit. Patty's airplane didn't

act that way at all. The

Extra 260 is a pleasing combination of thoroughly conventional control

and performance parameters, but the decimal point has been moved over

on every single one of those parameters. The Extra climbs faster, rolls

quicker, and pitches more rapidly, than practically every airplane

in the world but it doesn't require the pilot get a brain implant to

enable figuring out the sequence of events. |