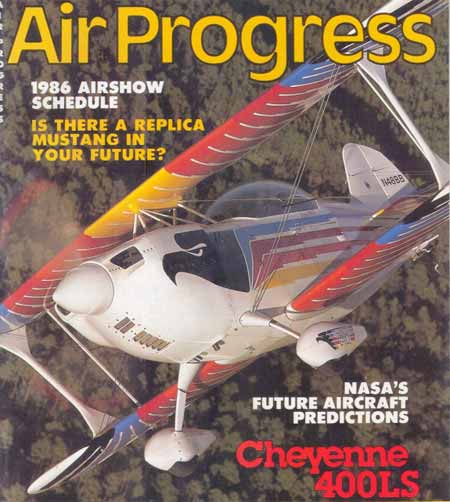

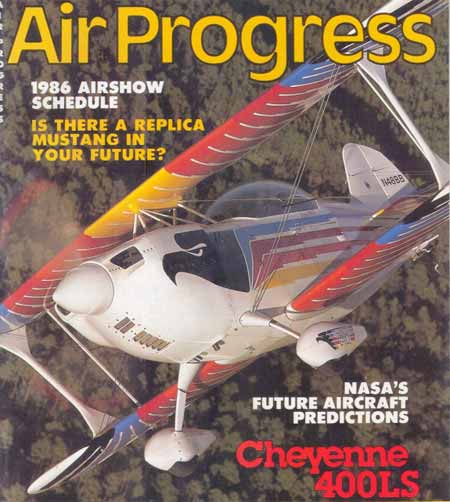

If one airshow airplane has captured the public’s

eye in the past decade, it has to be the Christen Eagle. Everywhere

you look, you see Tom, Gene and Charlie locked wingtip-to-wingtip on

some magazine cover, their Eagles glistening in the sun. Every time

a movie company or magazine needs an airplane with “character,” central

casting orders in an Eagle. We even got to see Betty Davis as a crusty

old instructor who used an Eagle as a mount in a TV movie about handicapped-person-earns-her-wings.

You find their brightly colored, totally identifiable (and trademarked)

feathered paint jobs everywhere. So, why did it take me this long to

bum a ride in one? A lot of wrong places at the wrong time, I guess.

|

| Eagles are good inside or out and faster than

the equivalent Pitts. |

The Christen Eagle is the aeronautical personification of Frank Christensen.

Frank is a man who can only be described as a true mover and shaker

who knows only one way to do things…the right way plus a bunch. Founding

a manufacturing company when he was still in college, he became so successful

that, when he was bought out by a larger firm, he suddenly found himself

a young, aerobatically-oriented multi-millionaire. At that point he desperately

needed a place to invest not only his money but also the boundless energy

that marks men who are prone to that kind of success. So, he founded

Christen Industries on his Fly-in Ranch in Hollister, California and

began producing super high-quality components for aerobatic aircraft.

His products include seat belts, inverted fuel and oil systems and wobble

pump/gascolators. Actually to say that he “produces these items

is to over simplify, since anything his company produces is so high

in quality as to be outrageous. And, yes, to answer the next question;

you pay more to own the very best.

In the early 1970s, not content with the

current crop of aerobatic airplanes, the Pitts Special and the still-being-developed

Laser, Frank decided to get into the airplane design game. Initially

the design would be for his own use but, later, for public consumption

as well. Although he actually hasn't said as much, certainly part

of his dissatisfaction with existing air-planes had to do with trying

to fit into a Pitts Special when you are in the neighborhood of 6

ft 2 in tall. At one point Christensen did purchase an unfinished

S-2A airframe with the idea of modifying it for his own use. At last

report, that project was never finished since he decided to start

from scratch and design his own airplane.

It isn't known whether he actually planned on developing such an unbelievable

kit or whether it just "growed" as he went along. Regardless,

the final result is an airplane kit that truly is as snap-together

as you can get with an airplane and it is the standard for all others

to strive for. Approaching it as only he knew how, the Chirsten Eagle

kits surpass even the finest radio controlled model kit in terms of

attention to detail, completeness and well thought-out instructions.

IGNORING THE KIT, THE INSTRUCTIONS THEM-selves are a masterpiece in

planning and presentation. Comprised of a raft of three

ring binders, each of which is dedicated to a specified component and

series of operations, the manuals include exploded views and step-by-step

assembly instructions that en-able a middle-aged housewife from Bayonne

who hasn't figured out her bank statement to build a Christen Eagle.

Certainly one step of building a homebuilt air-plane that scares

just about every homebuilder is the welding of all the steel assemblies.

This step has been eliminated from the Eagle Kit because the fuselage

and all the other little goodies made of steel are welded and painted.

In fact, the kit is so complete that early in the program Frank had

a hassle with the FAA concerning their 51 percent rule.

The dread "51% rule" which applies to homebuilt kits say

that the builder must contribute at least 51 percent to the finished

product. As one would guess, since this includes material and labor,

the establishing of what constitutes 51 percent isn't easy and is subject

to a lot of interpretation. In the case of the Eagle, it meant producing

a kit with uncompleted ribs. The first few airplanes had finished ribs

but he had to change that procedure.

The way the kit reduces rib building to coloring book level is typical

of the entire airplane. The builder receives a long piece of channel

tooling into which he lays a piece of rib material, a strip of small,

square spruce. By running a razor saw through grooves precut across

the channel, he winds up with the right number and shaped pieces. Then

he pops these pieces into a rib jig that holds everything together

with a clever arrangement of eccentric clamps. A little gluing and

gusset stapling and the rib is done.

Certainly one of the most common comments about the Eagle is that it

is a slicked-up S-2A Pitts Special which, to a certain extent, may

be true. However, the similarity between the two airplanes is more

unavoidable than intentional. When you decide to build a

high-performance, two-place unlimited aerobatic biplane using a 200

horse Lycoming engine, there aren't a whole lot of things you can do

that would be called wildly original or different. We have yet to see

our first composite biplane. So, just as the Travel Airs and Wacos

are similar, so are the Eagle and Pitts S-2A.

Incidentally, any conversations about the similarity between the two

airplanes have to include the fact that Frank Christiansen owns both

the Eagle company and the Pitts company. When he bought out Pitts Aerobatics,

he became the producer of bipes of both home-built and factory made

varieties. With the quicksand of liability insurance working its way

up past his ham-hocks, the near future may find us with no one producing

akro-bipes as Frank heads for the high ground.

GO TO NEXT PAGE

|