When talking about legendary aerial anachronisms, it's customary to begin with "Boy, I remember the first time I ever saw a (insert name of a legendary aircraft to help in establishing your own rightful place in aviation history) . . ." This is not the case with the J-3 Cab. In the first place, I challenge anybody over the age of 35 to remember the first Cub they ever saw. In the second, even though the Cub is one of aviation's genuine mileposts, a development which gave general aviation a great boot in the pants, the Cub has never been the sort of thing of which hairy chested hangar tales are made.

Cub stories are always of a whimsical nature. "I remember falling out of one when trying to get out of the front seat," or "We always used to glide down over the tree tops by the river bottom to surprise the girls skinny dipping." There are damned few blood and guts Cub stories because, except for frontline liaison stories, the Cub just wasn't made for blood and guts situations. Besides, everybody has flown a Cub, so too many people can figure out whether you're lying or not. Better to stick with Leopoldopf Colibris, or Polikarpov I-16s. With those, not many can tell whether your facts are straight.

Even though the perennial yellow Cub may be plain vanilla, there is a Cub mutation that is guaranteed to give rise to a few stories and definitely is capable of inspiring blood and guts narrative. This mutant is known as the "clipped Cub."

Originally, when you spoke of the clipped Cub, you were talking about one specific type of animal. These days, however, thirty-odd years after the first Reed Conversion was STC'd, you have to be very careful what type of machine you are talking about, because the Reed clipped wing conversion was just the beginning in a whole new saga of the J-3 Cub.

The original Reed conversion did nothing more than shorten the wings 40 1/2 inches on each side. No, this wasn't done by whacking away at the tips, as many folks believe. Rather, the inboard forty were sawed off, the attach fitting holes redrilled and the wings thrown back on. A few other little goodies had to be done, such as installing a vertical "U" shaped stiffener that bolted vertically to the spars and picked up the upper lift strut bolt. This was needed because when the wings and lift struts were shortened, the strut intersected the wing at a different angle, which introduced eccentric loads on the original lift strut attach fittings, a definite no-no. This changed strut angle also meant the fuselage strut fittings had to be heated and bent.

The supposed purpose of the Reed conversion was to take a little of the Cub out of the Cub. It cut down the float on landing, made it less of a cork in rough air, made it stronger because the bending moments were less and speeded up the roll rate because the wings were shorter. It is highly doubtful if any Reed conversions were done to help the airplane's stability. It was the last two points, the increased strength and roll rate that caught everybody's eye. Here was a way a couple of guys could spend a weekend with a sabre saw and welding torch and produce their very own 65 hp acrobatic machine. Incidentally, the Reed STC applies only to wood spar Cubs, although I believe there is an STC for chopping aluminum Cub spars.

A Reed Cub looks just exactly like any other Cub, except that there is only one short rib bay between the ailerons and the fuselage, as compared to a couple bays in the stock Cub. However, the biggest majority of clipped Cubs are pretty easy to identify because the builders seldom stop with trying to increase their "stability" or cut down on the float. These days, the Cub is like the 1932 Model B Ford used to be, before the price went out of sight. When I was a kid, if you could get a fat motor under the hood, you put it under the hood and, if it didn't fit, you moved the firewall or left the hood off. Clipped Cubs now fall into the same sort of street rod category. The originals may have been 65 hp, but there are precious few of them still flying on that few ponies. 85 hp is the norm, with C-90s and 100 hp 0-200s being as common as ladybugs.

A goodly number of

real hotrods have been built around the clipped Cub with 150 and

180 Lycomings shoe-horned up front, the fuselages clipped and

the wings replaced with symmetrical Taylorcraft panels. These,

of course, are licensed "Experimental" because they

don't conform to the Reed STC. What a blast it would be to build

a 180 hp J-3 with T-craft wings. You'd use the original style

open cowl, paint it yellow with the black lightning bolt and then

go looking for Arrows and Cutlasses. A 180 clipped Cub is good

for 160 mph in cruise and a 3,000 fpm rate of climb, or better.

You'd have guys with Wichita sheet iron birds swearing at their

mechanics because this dumb yellow Cub just walked away from them

. . . upside down.

A goodly number of

real hotrods have been built around the clipped Cub with 150 and

180 Lycomings shoe-horned up front, the fuselages clipped and

the wings replaced with symmetrical Taylorcraft panels. These,

of course, are licensed "Experimental" because they

don't conform to the Reed STC. What a blast it would be to build

a 180 hp J-3 with T-craft wings. You'd use the original style

open cowl, paint it yellow with the black lightning bolt and then

go looking for Arrows and Cutlasses. A 180 clipped Cub is good

for 160 mph in cruise and a 3,000 fpm rate of climb, or better.

You'd have guys with Wichita sheet iron birds swearing at their

mechanics because this dumb yellow Cub just walked away from them

. . . upside down.

I guess I've had my share of fun in Cubs, clipped and otherwise. I've chased girls down river banks, sneaked around ridges to surprise coyotes and landed on top of moving trucks. And, like everybody else, I've done probably a thousand loops, two thousand rolls and a million spins in Cubs. But that was a few years back, more than I'd like to admit to. Now, when I see a nice, stock looking, yellow clipped Cub, I can't help but stop and look at it. It can't hold a candle to a Pitts in performance, but there is nothing prettier than a well done clipped Cub. And Joe Eubanks, of Daytona Beach, Florida, has a well done clipped Cub.

When I saw Eubanks' Cub, I was in the process of strapping on a Jungmann, but the urge was still there to unbuckle and walk over to look at it. My generation of pilot can trace its roots right down to the Cub, and I can trace my early aerobatics down to the same source. So nostalgia may have a hand in coloring the way many of us look at Cubs in general and especially those of the clipped variety.

As it happens, Joe Eubanks had just taken delivery of his shiny yellow fabric toy and was looking for any excuse to fly it. Give him a reason ("Hey Joe, is the beach still there? Let's go check."), and he's gone. I said something like, "Boy, is that thing cute." He said, "Right, let's go flying." Joe's a real pushover.

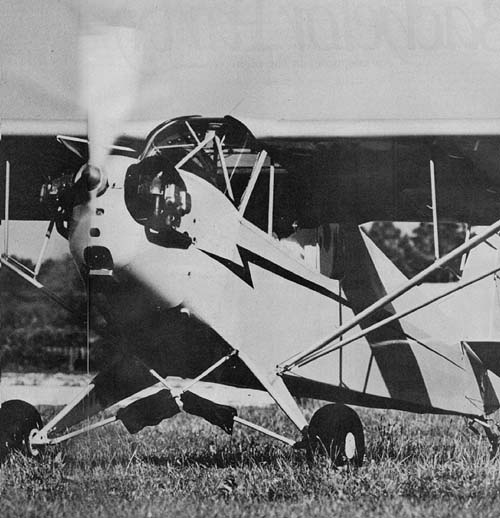

Joe's clipped Cub is a classic example of what the breed is all about. Except that it has a few little tricks that developed fairly recently, it could be sitting on the ramp in front of Any-FBO, Inc., Small Town, Kansas, circa, 1951. Many folks can look at a plane like Eubanks' and not even realize it's a wolf in sheep's clothing, or at least a Pekinese in drag. It looks exactly like a restored J-3 because it's hard to judge the wing length without something to compare it to. Black lightning bolt down the side, jugs hanging out in the breeze, Cub decal on the fin, fat bagel-like tires . . . it's all Cub. Except it's not.

What sets Joe's airplane a little apart from the standard Reed clipped Cub is its detailing and the extra thought given to its new role as acrobat. Rather than doing just the Reed mods, who-ever built the airplane up originally worked in all the details that have been found to make clipped Cubs a little better. One of these is doubling up the ribs, putting an extra one between each of the originals. This not only makes the fabric panels smaller and stronger, but eliminates the age-old (or is it old age) clipped Cub problem of ribs which break. The original rib spacing was just fine for flying out of a farmer's field, but repeated bashing at 4-5 gs would cause the aluminum built-up ribs to break and you had to open up the skin to repair them. Similarly, the rib stitching is tighter, allowing a little extra diving speed without popping some fabric loose.

These days, it's possible to build a practically brand new Cub, since Univair of Denver, Colorado makes just about everything you'd need from new cowling to ribs and landing gears. Granted, Wag-Aero of Lyons, Wisconsin does make a completely new J-3 kit, the CUBy, but it's a homebuilt, and can't be licensed in standard category. Also, none of the CUBy parts can be used on a stock J-3 because they don't have an FAA PMA (Parts Manufacturing Approval) number. Univair's stuff, on the other hand, carries the PMA number because they bought the licensing rights from Piper, so they are the manufacturer of record. This is all basically a crock, since the only real difference is a rubber stamped number, but that's the way the system works.

The nice part about having a supplier like Univair around is that Cubs like Eubanks' can be built up using brand new sheet metal. The cowling and boot metal on Joe's airplane doesn't have so much as a fingerprint on it, which makes for a super sanitary appearance. Also, an airplane like Joe's can be built using brand new ribs and spars, something worth considering if you're thinking about doing aerobatics on parts that may be as much as forty years old.

Crawling on board a Cub, clipped or otherwise, is a great way to slip a disc. It makes everybody look, and feel, like an arthritic giraffe, because everything, the struts, the door and the seats are carefully arranged so that they get in the way, no matter how you approach them. Then, once inside what look like uncomfortable seats from the outside turn out to be truly awful. The front seat is okay, except the rudder pedals are so close you find your knees in your shirt pockets. The back seat, which is really just a canvas sling, is akin to sitting in a hammock at a 45 degree angle. And that back seat, where you solo the airplane, is usually beefed up with stronger canvas, because more than one clipped J-3 akro pilot has found his butt falling through a rapidly widening rip in the bottom of the seat.

Joe's machine has a 90 hp Continental with a pressure carb, which used to be the hot setup and still ain't bad. Because of the carb, Joe, who was wedged in the front seat, had to work a wobble pump a little to get the fuel pressure up before somebody flipped the prop through a couple times. "Switches on, brakes and cracked!" I hollered. The prop was flipped once more and the little Continental started chortling away and off we went.

Taxiing out to the runway, I was once again reminded of the incredibly bad brake system the Cub has. I've always hated heel brakes and the Cub's are the pits, because you can't reach them when you need them and when you do, they don't work worth a hoot.

It's a good thing a Cub is a Cub and you really don't need brakes anyway. It's only the Cub's gentle nature that kept an entire nation of pilots from rising in a revolution and forcing Piper to go to toe brakes, or at least heel brakes that can be used.

Of course, as a trainer, the brakes were situated just fine. Since a student could hardly reach them, he seldom got himself in trouble with them. He also learned to get himself back on the straight and narrow with the rudder rather than relying on brakes, such as they were.

When it's springtime in Florida, and it was, a Cub might as well not even own a door, because nobody in his right mind closes it. As I lined up on the grass and started shoving the throttle up, I gazed out the open door and wondered how many thousands of pilots and passengers have done the exact same thing.

The Cub isn't the standard for docility and fun for nothing. A couple of plaintive bleats from the Continental, a few gentle suggestions from my feet and we were off. But not in much of a hurry. A 90 hp Cub in Florida with two folks on board isn't going to win any time-to-climb contests. About 600 fpm seems to be average. That will go up to 800 fpm or more with only one on board and a little cooler temp. The clipped wings suck a little out of the climb, but the 90 hp makes it all back up. However, as a slight amount of thermal turbulence started working us over, it was obvious even to one who hadn't been in a Cub for some time that losing nearly seven foot of wing makes the Cub a lot more sure footed in the bumps.

At altitude, I racked it around a bit, trying to get back the feel of that tall stick and those so-so ailerons. As it happens, Cub ailerons are one of the areas that a lot of guys modify when they go the hotrod route. Some seal them, some servo them, but no matter what you do, the roll rate is still some-what on the leisurely side. It's a lot better than stock, but it's not going to thrill the underwear off a Pitts pilot.

Satisfied we were in that particular piece of airspace all by ourselves, I ducked the nose down for a second, got 110 mph on the gauge, pulled the nose up and fed in aileron. Then I fed in some more. Up and over the top, easy and graceful, as a roll should be. The Cub had no problems with the maneuver, but it was obvious it wasn't going to go rushing through it, no matter what I tried to make it do.

Aileron rolls, barrel rolls, four points (sort of), and slow snap rolls (not recommended without good tailwires), we went right down the menu. And it was fun. I think I had forgotten what it was like to have to actually "fly" an airplane through a maneuver. I'm so used to just pointing the nose, wiggling the stick and the Pitts does the rest. Not so with the clipped Cub. If it's going to do the maneuver at all, it will be because you've carefully balanced the dynamic and aerodynamic forces acting on the machine and made its flight path teeter along on the tightrope that is aerobatic flight. Ease up for a second and the maneuver just won't look good. Of course, you can botch it up six ways from Sunday and the clipped J-3 will just shrug its shoulders, fall a little ways, (just to get your attention) and then will sort things out all by itself.

Loops are the clipped Cub's strong point. 110-120 mph (redline) on the clock, an even, low G pull and the nose easily climbs an invisible rope, arching its way into the domain where the blue is down, the green up. Gently relaxing the pressure on the top rounds out the loop, taking some of the "eggy-ness" out of its shape. Then the nose is falling down and it's time for a little more back pressure to bring everything back into level flight.

I remember the days when I thought nothing of honking a clipped Cub around as if it was a 450 Stearman. It would do a fair to terrible English bunt (half an outside loop from the top) and would glide like a stone inverted, gas running out of the cap all the time. Eubanks' had a vented, inverted fuel cap and the fuel injection would let it run a little longer, but I somehow didn't feel like playing those kind of games. I was a lot younger in those days. So were the Cubs.

Power back, nose up. Bam! The stick comes back and a rudder goes down. The Cub whips over into the prettiest little spin any airplane can do. One, two, three, four. Opposite rudder and a slight relaxation on the back pressure. No need to jam the stick forward. The Cub will spin only if you hold it in. Relax a little and it will pop out before you're even ready for it. Since a Cub, even a clipped one, will glide well enough to be able to slope soar ridges in a strong wind with absolutely no power, the best way to lose altitude is in a spin. And that's exactly what we were doing.

It was on final that I recalled the only really noticeable difference between a stock J-3 and one that's clipped: losing seven feet of wing is bound to do things to your glide ratio. Where a regular Cub will bob and weave on final, threatening to keep on gliding past Peoria, a clipped Cub, sits there like a Mustang, riding a taut wire attached to the ground. It usually surprises first-time clipped Cub pilots to find themselves having to use power on final. I personally like it. It allows you to handle a lot more wind and you can put the airplane right where you want it.

Once down into ground effect, the clipped Cub still allows you to make those beautifully soft, whispering landings that grass runways and Cubs were made for. A gentle whoosh and you're down. There aren't many things in an airplane that can beat that kind of feeling.

Right now there is a legion of clipped Cub fanatics who are screaming that we didn't touch on this or that detail. They're yelling that we missed the importance of the larger lift strut fork or the beefed up strut mod. We didn't talk about aileron bracket problems, or threading rudder cable through the struts as a safety. They are right. There are a dozen things, maybe a thousand, I've missed, but the best way to learn all those is to start climbing the aerobatic ladder the same way a lot of us did. Go find a clipped Cub and an instructor and have at it. You'll never regret it.