|

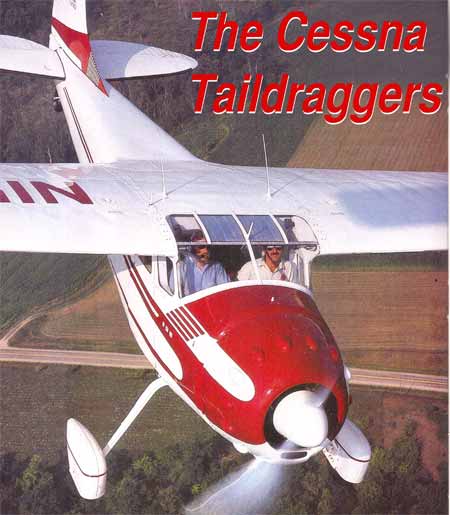

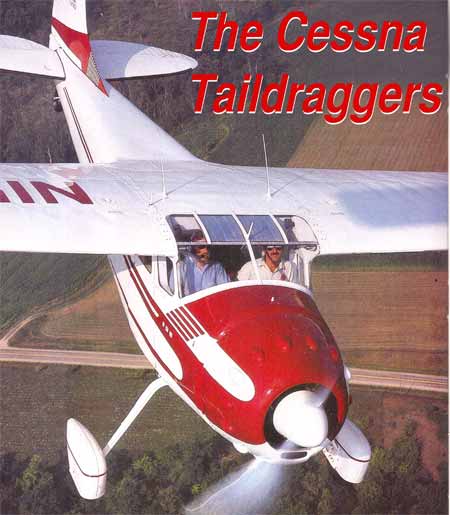

Flying the Cessna Taildraggers |

Cessna Built a

Bunch of Tailwheel Airplanes and we Review Them All |

Cessnas and nosewheels: They go together like bagels and creamcheese, hot dogs and mustard, beer and pretzels. They go together so well, in fact, nearly half of the General Aviation fleet is comprised of nosewheel Cessnas. However, if you were to ask a confirmed antique or classic buff about the combination, they'd say Cessnas and nosewheels go together like scotch and buttermilk, pizza and asphalt, or eggs and sauerkraut. Long before Cessna was The Great American Nosewheel Baby Carriage, it was simply The Great American Airplane. That was when the tail was where God meant it to be — on the ground. To a lot of folks, there is something vaguely obscene about a Cessna with its tail in the air. Like it ought to be wearing diapers or something. Contrary to popular belief, the nose-wheel is not a recent invention; nor is it a device of the devil, sent to earth to rob pi-lots of their abilities and manliness. In reality, the nosewheel was there first. Look at the Wright guys and Curtiss and all the rest of the early aerial sodbusters. It is difficult to say exactly who came up with the first tailwheel, but as far back as Santo Dumont's early designs it was already in vogue. Despite its lack of directional stability, the tailwheel was lighter to build, easier to install, and took less structure. Wait a minute! That's not exactly true. Yes, the taildown stance was around early on, but don't lose sight of the fact it wasn't with a tailwheel. It was a tailskid and a tail-skid was one hell of a lot more stable than a tailwheel on the grass runways that first served as airports. A tailskid digs in a little on touchdown and, in so doing, puts a pretty good amount of both backward and sideway resistance right where you want it — in the tail. This factor keeps the tail behind the nose because it is being dragged through the grass. Put a tailskid on pavement and all hell breaks loose. In the mid-1950s, when the nosewheel came into vogue, few pilots bemoaned the passing of the tailwheel. It was amazing how fast rental Cubs and Champs disappeared — replaced by C-150s and Tri-Pacers. By the early 1960s, it became increasingly difficult to find a flight school still utilizing tailwheel airplanes. Even though, as a trainer, the Cessna 120/140 was a real breakthrough because it could do both basic training as well as cross-country flights, it was replaced practically overnight with C-150s. Instructing became much easier and the "If you can drive, you can fly" thought pattern was bringing lots of new pi-lots into the fold. By the late 1960s, tailwheel Cessnas, with the exception of the C-180/185, were relegated to used-airplane status. Many aircraft rapidly approached the stage where they were left to rot on back tie-down lines. It wasn't until the late 1970s and early 1980s that the concept of the "classic" airplane began to catch on. The classic airplane's increase in popularity paralleled the ridiculous increase in the price of new airplanes, as well as the growth of the sport airplane movement. Of course, it helped that there were several generations of new pilots who didn't remember when tailwheel Cessnas were simply used airplanes. They saw them as something semi-exotic, cornpared to what they were trained in and, suddenly, tailwheel Cessnas weren't just old — they were classic as well. The very first Cessnas that actually looked like we think of Cessnas looking were the AW series of the late 1920s. These were neat airplanes! These aircraft were the Centurions of their day, since the planes sported four-place enclosed cabins and a one-piece cantilever wing that was about as clean as anything built — and they originally had tailskids. By the mid-1930s, many runways were being paved and Cessna's next series was the Airmaster, which was designed for that environment. If the AW was sleek, the Airmaster had the lines of a bullet. Then, as World War Two came along, Cessna's biggest contribution was the unlovely but wildly useful Bamboo Bomber — more properly known as the UC-78 ("Useless 78") and the T-50. As a twin-engine airplane, it was marginal, but that's exactly what made it such a good multi-engine trainer. After the war, Cessna, bless their little hearts, couldn't force themselves to totally leave the golden age of the 1930s behind. Combining what they had learned about sheet metal, which is curious considering the UC-78 was all tubing and 2 x 4s, with their love of cantilever wings and round motors, they built the ultimate in useful classic airplanes: The 190/195 series. Tail on the ground, big round Jacobs, slick as a dream, and commodious as a living room — what was not to love? When Cessna got into postwar-boom mode and focused on the little airplane market, they designed the two airplanes that have survived to this day as current designs, the C-170 four-place and the C-120/140 two- place. Both soldiered on to the very end of the Cessna single-engine experience with nosewheels as the 172 and 152. In the autumn of 1950, Cessna got back into the Warbird game when they started punching out the first of about a trillion L-19 Bird Dogs. Utilizing a bunch of C-170 parts, a 213 horse Continental 0-470 engine, and more flaps than wing, the company built an airplane that could operate out of a ball field and gave generations of FAC pilots a front-row seat during several wars. The L-19 demonstrated what could be done with big engines and even bigger flaps, and the lesson wasn't lost on Cessna management. All their airplane needed was a larger cabin and more motor, and designers theorized they'd have a winner. After making those changes, Cessna named their new airplane the 180 and they were right. The Cessna 180 became the workhorse for leagues of farmers, bush pilots, and those needing a pickup truck with wings. Ordinarily, it would be easy to say the death knell of the tailwheel was sounded when the factory modified a 170 with a nosewheel and new tail surfaces and called it the 172, but that would be inaccurate. As long as Cessna was building single-engine airplanes, they were building tailwheel airplanes, since there has always been a market for such craft. Cessna even certified a new model, the 185, in the 1960s which was, in a way, the same concept as the C-195 of two decades earlier. With the 185, they stuffed as much cabin as they could behind a big motor and even bigger wings and flaps. This was one serious working airplane. To the pilot looking for an airplane with a touch of nostalgia and a ton of utility, there are over 60 years of Cessnas from which to choose.

AW SERIES

|