Rocketing upwards at 3500 fpm on instruments, it was a sudden shock to come blasting through the top of the clouds into clean blue sunshine. I reached awkwardly up to the top of my helmet and pulled the tinted visor down to dull the brightness. Then my temptation and common sense curves crossed and my right hand reached quickly into the corner with the stick. A quick smooth roll to satisfy a momentary urge and we continued the climb. It was, I could already tell, going to be an aerobatic machine that would give you daydreams for months. It would be boring to read details about the next twenty or thirty minutes of flight. It's impossible to give the exact feeling that comes with pulling up into a vertical roll that fills the canopy with twisting blue and white reflections. In my own mind I can still feel the freedom of barrel rolls so big that you could live a lifetime in the sustained arced flight path at the very top. But I can't give that feeling to others. Aerobatics is one of those things that, if you don't do them, you really can't imagine them. And, if you can't imagine them, you'll never live, even vicariously, the mind bubbling joy to be found in an aerobatic airplane that knows only speed and climb and presents few limitations of its own. The only aerobatic restrictions on the -37 are no snap rolls, and inverted flight must be limited to 30 seconds. That's it!! With its Hershey bar wings and virtually unlimited speed envelope (372 knots indicated is redline!) it's made for doing just about anything. One of the favorite horror stories of ramp rats and hangar fliers is the way a T-37 recovers (or doesn't recover) from a spin. It's supposed to be stuff only for super heroes, or in my case, for a guy who isn't afraid to eject if things get out of hand. So, we did a few spins. Ron declined demonstrating even one. He just cautioned me about doing the recovery exactly right and away we went. At our weight, the stall happened at about 75 knots and I stomped rudder and sucked the stick back as it broke. The outside wing snapped over the top and we twisted down into the first several turns. In the first turn the nose went down and then came back up almost to the horizon and then went down again. It oscillated like that several times before it settled down into a surprisingly flat attitude (compared to a C-150 or Cub). The recovery is something right out of a NASA handbook. You bang the opposite rudder to the floor, wait one turn (which ain't long) then nail the stick to the forward stop-ALL the way forward. For a second, the spin appears to speed up. It whips through about a turn and a half and suddenly bangs to a stop. At that point, you've got to be on your toes and get the stick back pronto or you'll tuck under into a possible inverted spin.

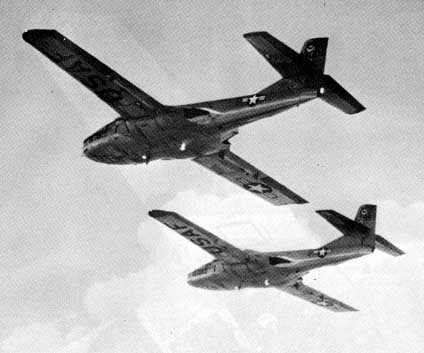

Done purposely, the spin is no big deal, but if entered accidentally or if recovery isn't exactly by the book, you've got real problems. In an accidental spin, you're supposed to initiate recovery by "pro-spinning" it... back stick and rudder in the direction you "think" you're turning. That establishes a stable spin and you then recover normally. If you don't get the controls all the way against the spin when recovering or foul up the sequence, it goes into an accelerated or aggravated spin mode. If it aggravates, you have to pro-spin it again to reenter a standard spin before it will recover. Of course, the ultimate recovery, in case you're running out of altitude and ideas, is the pair of yellow handles down by your knees. We circled down to an auxiliary field and Ron did his best to make me into a military blowtorch jockey in the pattern. We'd fly a 360 overhead approach, going directly down the runway at 1000 feet and 200 knots. We'd pitch hard left, reducing power to about 60% and getting the gear out at 150 knots and flaps at 135 knots. I had expected to have problems controlling speed build-up but as soon as the speed brake was put out, it became a Cherokee or C-150, just a whole lot faster. Final was flown at 100 knots and holding a glideslope was no sweat. USAF policies would not let me legally land the airplane so we'd fly down within about 100 feet and I'd initiate a go-around. After doing this three or four times, I felt as if I'd been flying the airplane all my life. It was absolutely beautiful! All told, I wound up with about an hour and a half in the airplane and I can now see why the Air Force likes it so well. As a flying machine or teaching platform, it has few, if any, drawbacks. Its systems are extremely easy for a student to both understand and operate. This also means the airplane isn't going to have reliability problems or become one of those birds students keep jumping out of because of inflight emergencies. The teaching environment of the cockpit is as good as I feel a military cockpit could possibly be. In its side-by-side configuration the instructor can watch the student, point things out to him and generally have a much closer instructor/student rapport. The flight characteristics are such that an instructor can let a student get in very deep trouble, give him plenty of time to save it, and still have a margin of safety for himself. The one area in which this is not necessarily true is in final approach mode. Because of the excessive spool-up time of the J-69 and the moderate power available, a student would have to be watched so that he doesn't get too low and slow. If the T-37 has a weak point, it has two... its engines. The J-69 was originally a French design, a Turbomeca, and develops slightly under1000 pounds thrust. Contrast that with the J-85 whose newer technology gives it two to three times as much power for almost the same weight. The attack version of the Tweety Bird, the A-37, uses two J-85s and it's standard procedure to take off and then shut one engine down until reaching target. The other burner is lit only for the attack. With those engines, the airplane literally leaps off the ground and goes straight up. In its trainer version with J-695, a 4,000 foot runway is needed to feel comfortable and supply a margin of safety for aborted takeoffs. The only other limiting factor of the T-37 is its short fuel supply. You have to really fly the numbers and maintain a strict profile to get more than 2 hours out of it. This negates some of its speed capability. It carries a total of 309 gallons, but it's burning 132 gallons an hour at 272 knots true and 186 gallons/hour at 335 knots true Both of these figures are based on cruising at 20,000 feet. For a military airplane, the airframe is extremely simple. Almost all the systems are accessible through either huge inspection ports or in the nose bays. The control system uses old fashioned cables and pulleys with an occasional pushrod, but there's no hydraulic boosting used anywhere. The instruments and avionics are straight forward and the fuel control system isn't complicated. It would be a relatively easy airframe for a civilian to maintain. Will we ever see the airplane being flown by big buck civilians? It's hard to say. It doesn't have the machismo and emotional appeal that the F-86 has and you have to be out of your mind in love with something to pay that much for it. Also, it would have to have external fuel tanks, such as those on the A-37, to be really useful. The noise alone might prevent the feds from letting it be certified in any category. On the other hand, maybe somebody like Paulsen or Gausman will put two (or even one) J-85/CJ-610 engines in one and begin scaling the certification ladder with it This could all be pipe dreaming because the USAF isn't about to start

dumping their T-37s on the surplus market. For one thing, they just

finished IRANning a whole batch of them, bringing them up to zero

time standards. Also, there isn't a single trainer that I know of on

the drawing boards to replace it. There are some dandy foreign trainers

the USAF could use, but I seriously doubt if Congress is going to let

our balance of trade and the current buy-American campaign suffer that

kind of indignity. Beside, there isn't a hell of a lot the Air Force

stands to benefit in a new trainer. The T-37 is cheap (new copies are

being sold by Cessna for around $350,000), it doesn't burn much fuel

(as jets go) and it is a known quantity, so why change? Still, they

have to be breaking a few of them now and then and nothing flies forever. For lots more pilot reports like this one go to PILOT REPORTS |