PIREP: Cessna 170B

We all know that the Cessna 170 is the progenitor of the ever popular, omnipresent C-172 . Or is it? At what point does an airplane design evolve itself out of existence? As I was walking around N1956C, a 1953 model Cessna 170B, I found myself comparing the machine to the grand-children it sired in such huge numbers. Yes, it did look like the 172 or vice versa, but not really. Certainly, the tail bears no resemblance to the current swept back version (which was probably designed by a marketing director's wife) and we all know that although 172s started with the same aft fuselage, they were shortly changed to mount the wrap-around rear window. Also, the cowling looks a little smaller and more pointed; probably a function of the six-cylinder 0-300 Continental it houses. And, oh yes, the C-172 has the tailwheel mounted at the wrong end of the airplane. Not only is the landing gear different, but the C-172 has gone through two versions since 1970... leaf and tubular springs.

Yep, the C-170 gave the 172 its start, but is it absolutely fair to say the 172 is a warmed over 170? At this stage of the game, with the 170 only a few years short of being forty, I think it's only fair to say they have evolved every bit of the old airplane out of existence and a 1985 Skyhawk, should they decide to build one, would be as far removed from the C-170 as the current model homo sapiens is from Neandertal man.

Certainly, one of the items which separates the 1985 version from the original 1948 variety is a matter of dollars. Lots of them! Today you can pick up Cessna 170s starting at $9000 and going as high as $18,000 and have yourself a semi-classic design which does almost the same job as the 172 which, in 1985 dollars, runs in the neighborhood of 75,000 big ones. On that basis, it makes a hell of a lot of sense to turn your eyes bloodshot perusing Trade-A-Plane and walk your feet sore covering outlying airports in search of the 170 of your dreams. Two fellows who did just that are Dave Hoover and Vern Lewis of Sparta, New Jersey.

Not looking for a cream puff 170,

Hoover and Lewis spent their time searching for something that

would be considered "sound"; no corrosion, a minimum

of dents and dings, and a medium to low time engine, which wouldn't

give them any trouble. And, oh yes, one that was on the bottom

of the price range. They found N1956C in Phoenix, closed the deal,

and shortly thereafter putt-putted across the country back to

their New Jersey home base.

Not looking for a cream puff 170,

Hoover and Lewis spent their time searching for something that

would be considered "sound"; no corrosion, a minimum

of dents and dings, and a medium to low time engine, which wouldn't

give them any trouble. And, oh yes, one that was on the bottom

of the price range. They found N1956C in Phoenix, closed the deal,

and shortly thereafter putt-putted across the country back to

their New Jersey home base.

I too had been flipping through Trade-A-Plane looking for a 170 and it was with a certain amount of surprise I found theirs tied down no more than 50 feet from the hangar door that protected my Pitts from the vagaries of the New Jersey environment. So seldom do I have the opportunity to fly an airplane from my home base that it was amusing to find it was owned by a good friend, Vern Lewis. In answer to my questions he said, "Let's go flying." (He freely admits you don't have to twist his arm too hard to get him into the air.)

Vernon had virtually no formal tailwheel time when he bought the airplane so I watched with great interest as he rounded the corner onto final to our 2000-foot strip at Aeroflex-Andover and proceeded to make one of the prettiest three-pointers I've ever seen. I walked over to the airplane and looked at it as if I were seeing one for the first time, in an effort to weed out those things which set it apart from its modern day cousin that the prospective buyer might be interested in knowing. One of the first items I noticed in boarding the airplane was the step is well located for getting into the front seat but boarding into the back without that tricycle gear is a little more difficult. However, once in the back seat I found it to be quite commodious with much more leg room than I had imagined. The same is true of the front. As far as leg room and room in which to slide your buns around, you couldn't ask for more.

When I scrambled up into the front seat, I was more than surprised by the visibility over the nose . . and I do mean visibility over the nose. Since virtually all my current flying is done in taildraggers I have become used to equating having the nose wheel mounted on the tail with not being able to see straight ahead. Not so, in the 170. In actuality there's little difference between the visibility in a 170 versus that of a 172. Once you can see the runway, how much more do you need to see?

I was certain, however, I was going to have a hell of a time getting my references up. With so little airplane in front of me, I wasn't sure I'd know the three-point attitude when I saw it and I'd tend to over-rotate on landing and snag the tail wheel first.

As I slid the seat forward, I felt the seat pins lock into position but did the old "Cessna Shuffle" (where I rocked fore and aft in the seat) to make, sure it was indeed locked. More than one Cessna pilot has found his seat unlocked and sliding towards the rear during takeoff . . . something which gets your attention!

When I went to fire up the Continental it was easy to see I was out of my element since I pushed the mixture in and immediately reached over and pulled the starter handle. The little Continental cranked over half a dozen blades and then Vern reached over and turned on the mags. All right, so I wasn't an expert yet!

Taxiing was pretty much as i had expected since you can see clearly over the nose and directional control is no problem. I was surprised to find the tailwheel steering very much on the sedate side and required a punch of the brake now and then to tighten up a turn. As I was to learn later the sedate personality shown in taxiing applies to everything throughout the entire airplane. Intended to be flown by the weakest link in the pilot chain, any type of "quick" handling-either in the air or on the ground-was designed out.

I ran a mag check at 1700 rpm and got my first dose of the Continental cacophony. I had been told that 170s almost always need a certain amount of soundproofing and this was the first indication the legend was true.

The handbook said to make takeoffs clean unless you are on a short field and then you use one notch of flaps. So I ignored the flap handle, cleared for traffic, rolled into the centerline and shoved the power up to the stop. The airplane responded exactly like a Cessna, with no significant surprises in the way it accelerated.

After rolling a distance, I shoved the wheel forward to hoist the tail at which point Vernon said, "Higher, get the tail higher." Since I already felt as if I was about to dig a hole in the pavement with the prop, I didn't respond. But I should have. It turns out the higher you get the tail and the closer to level attitude you are, the more you load that spring gear and the steadier it becomes on takeoff. Since I was a little tail down, the airplane got light on its gear before it was ready to fly and I had a little trouble keeping the center line centered . . . in fact, I wandered off quite a bit. I could see where it would take a little time to get smooth takeoffs.

Vernon said to go for 85 mph for the climb, so as soon as the airplane lifted off the ground I poked the nose down trying to get 85 mph. I was surprised to see how long it took for that number to show up on the gauge. Once the needle worked its way around to the appropriate number, I gingerly brought the nose up to establish what appeared to be a climb attitude that would maintain 85 mph. Because you sit so high above the nose, it's difficult to believe you're in any kind of a climbing attitude because you appear to be almost dead level. Without putting a stop watch on it, it would appear that the VSI was about right, and 500 feet-per-minute was all we were going to see. At that point I asked Vern the critical question and he nodded his head saying yes, it did indeed have a cruise prop on it. We were a long way from gross and even though it was warm outside, it was obvious that in no case was this thing going to be a real barn burner in the climb department.

As we made it up to altitude, the visibility became one of the airplane's real strong points. You were never blind in any situation. However, out and out speed was not one of its strong points. At 2450 rpm and 2500 feet we were only indicating about 110 mph. I wanted to see how close the airplane came to the original advertised speed of 120 mph, so I pointed my nose north toward the closest local airport and carefully ran a two-way speed check at 2500 feet AGL. Doing my best to hold heading and altitude, I took time hacks over the center of both airports and was surprised when my trusty little computer showed me a two-way average of 119 mph, which is about as close as you're going to get to 120 without lying.

In talking, no, make that shouting to Vernon during the speed test it became readily apparent the soundproofing many owners have put in the 170 is well worth the extra weight. The six cylinder engine is smooth as glass but noisy as hell, and anything that can be done to quiet the cabin would be well worth the time and effort.

Except for the noise, I found our short cross-country to be extremely comfortable due primarily to the seating and general room the 170 offered. Since N1956C was a little ragged around the edges, you'd be hard pressed to say that it was luxurious. But, you would be even more hard pressed to say it was anything but comfortable, which, when coupled with the airplane's natural stability, makes it into a fine cross-country ship.

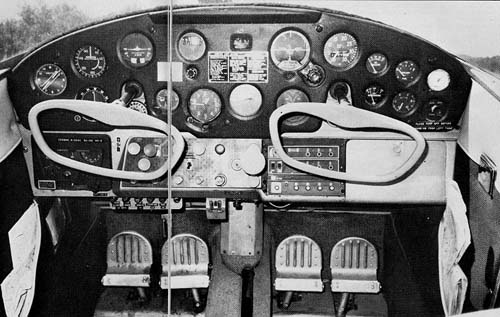

If there's one thing, which varies on 170s, besides the paint jobs, it's the instrument panels. Because the panel is so close to being the same size as the 172, i.e. it has plenty of room for radios, you find many of these airplanes modified with some of the very latest in get-me-where-I'm-going radio gear. And then you find a lot of them like 1956C; still carrying some of its original radio equipment, which is, combined with some of the later King series. In this case, we have an old Narco coffee grinder Superhomer and in the other corner a late slim line pack ... only part of which worked.

Once we had decided how fast the airplane went, it was time to find out how slow it went and what the stall was like. Carb heat out, power back, I brought the nose up to the horizon and kept pulling as it tried to fail. The speed came down to around 50 mph quite rapidly and I found the column right up against the stop before the airplane shuddered just a little and rolled very gently to the left. I repeated the performance several times to make sure I did have the ball centered and the roll wasn't induced by my size 10 Justins. The stall did have a very, very slight edge, but was mostly mush which turned into solid flight the second you released back pressure and added some power. When I ran the flaps out, the only thing that changed was the numbers got smaller and, oddly enough, the departure was not quite as noticeable.

The characteristic most noticeable during the stalls was how low the nose was in relationship to the horizon. It would be quite easy to accidentally get your attitude too high and burn off critical miles per hour during approach. This is especially true with flaps out.

The "B" model C-170s have a full 40 degrees (actually 38 to be exact) of flaps. And, as you get down to the last two notches, those big Fowlers slide out (straight 170 and 170A's have simple hinged flaps) and you find the Cessna has become a real parachute. However, bring the power back and let the nose come up just a few degrees and airspeed goes to hell in a hand basket.

As I headed back into the pattern, I once again found myself having my usual Cessna syndrome problem . . . not being used to an airplane that glides and having trouble getting them down from altitude. With the 170, even nose down and power back, I found myself catching thermals that were perfectly willing to let me stay up there for nothing.

As I headed downwind, I reminded myself how well the airplane glided and moved base leg out far enough to give room to play. I brought flap handle up one notch just before turning final and one more notch as I settled onto final. One thing about early Cessna flaps, there's absolutely no doubt when you're putting them out because the flap handle is the size of a broom stick and, when you have full flaps out, the handle sticks up between the seats and actually gets in the way of your elbow.

Vernon advised to hang onto 70 mph on final, bleeding that down to 65 mph and then 60 mph over the fence, which is exactly what I did. We had a fairly calm day going but the thermals off the lake gave a little shot now and then and I found the old 170 needed a fair amount of aileron to keep things copasetic. I could see where really heavy turbulence would work your butt off and you'd be going stop to stop. The cockpit would fill up with flying elbows in a hurry

There was a slight crosswind from the right and I let the airplane crab into it until I got fairly close to the runway. Then, just as I began to cross-control to get rid of the crosswind component, it disappeared All this time I was reminding myself to keep the nose down because the speed was falling through 60 mph faster than desired.

I leveled off at what looked like the right height and found that, once again, I was wrong. Holding off, trying hard to visualize the exact nose attitude which would put all three on the ground at the same time, I kept the wheel coming back and listened to the stall warning horn chirping away. Since the speed decayed a little too far, it didn't take long for the airplane to quit flying and drop the remaining few inches with a rather resounding thud. The spring gear soaked up the shock and did not throw us back into the air which it had every right to do.

I had hit on all three and was straight, so the airplane had no tendency to go darting off through the runway lights. I was fixated on the runway ahead to make certain the airplane didn't do any unscheduled sashaying. Both feet were ready to stomp on rudder and/or brake in case anything appeared to be going awry.

My feet got really bored, really fast. It wasn't until we were down to around 30 mph that rudder became necessary and then it was primarily to get on the brakes to slow down.

I was a little surprised at how the Cessna 170 flew, but I shouldn't have been. I have to keep reminding myself this airplane was designed in 1947, when T-Crafts and Cubs were the standards and everything else worked up from there. I guess maybe it's been a little too long since I've flown such airplanes. I've forgotten how low wing loading, high power loading airplanes fly. That's not to say they fly badly, but they do fly differently from the birds I've been bashing around most recently.

I was also surprised at how easy the airplane was to handle on the ground. The airplane had a slight "waddle" when running on its mains similar to an L-19, but that should be expected.

Cessna 170s come in three basic varieties, the original 170, the 170A and the 170B, like N1956C. The straight 170's are really nothing more than scaled up Cessna 140s. From a distance you would have trouble telling them apart. They have the same tails and fabric covered wings. Somewhere around 700 of the original models were built before they changed over to the all-metal 170As, with the totally new tail surfaces we tend to associate with L-19s and C-195s. Both airplanes use the Continental six banger with 145 ponies. It has been said this engine doesn't like 100LL at all, since it was designed to drink nothing but 80 octane. The "B" models introduced the Fowler flaps.

What do you look for when buying a 170? The normal stuff, i.e. damage or log book entries that indicate ground loops, corrosion in control surfaces and around the tail cone and a weary engine. Getting an airplane with a decent engine today, whether it is a 170 or any other used bird, is an absolute must. Since the price of overhauling engines has gotten so astronomical, you can very easily find yourself with an airplane in which the price of overhauling the engine is higher than the total value of the machine.

With the price spread of 170s being what it is, it makes sense to go out and buy the absolute best one you can lay your hands on one which someone else has already invested the time and money to paint, upholster and set up with new avionics and an overhauled engine. An airplane like that should come in at around $15,000-$16,000 or maybe a couple thousand more if it's a real showpiece. Even at that price it's a hell of a lot cheaper than buying a bargain basement 170 and then using your own elbow grease to bring it up to snuff. If you want an airplane to restore that's fine, but you're not going to come out with a cheap airplane. What you will have is an airplane that is totally yours and reflects your own taste but it's still going to cost more than those being sold at the top of the market.

If there were one modification I would make to the airplane

it would be more horsepower. I have never had a chance to sit

behind one of the 180 horse Lycoming conversions with the constant

speed, prop, but I have to believe it would make the 170 a whole

lot peppier. If you're going to do that, maybe you ought to look

at a Cessna 180 in the first place. But that's a different story.