PIREP

ON A KNOCK WURST

Come ride in our sky sausage; twiddle the controls of this portable

overcast.

AIR PROGRESS, Jan, 1971 • Text and Photography by Budd Davisson

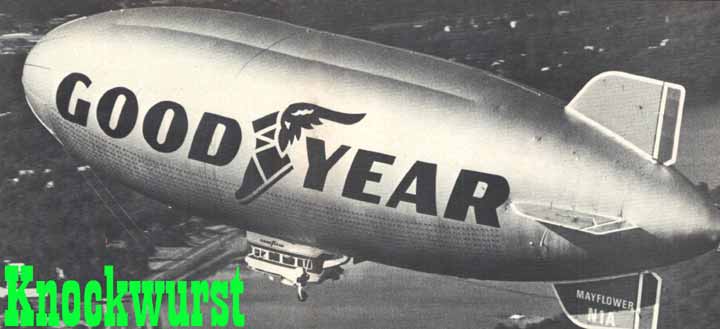

What has two engines, one wheel, and looks pregnant? You guessed it, a knockwurst with indigestion. Well, I got to fly one—if fly is the correct word. Goodyear owns and operates three helium-filled blubber-bags and admonishes the public to call them by their correct name, airship, rather than the more vulgar term blimp. Goodyear uses these flying hero sandwiches primarily for their publicity value, but there are spin-offs in research on lightweight fabrics and in triggering UFO sightings. They operate year round, and each one haunts a different section of the country.

Airships have been around since the invention of hot air. The world's first powered lighter-than-aircraft was Henri Giffard's airship in 1852. They've been a part of the military-industrial complex, too. During the 1930s, airships—rigid, semirigid, and nonrigid—reached gigantic proportions. Witness, dirigibles like the von Hindenburg and the USS Akron. Because it took "nothing" to keep them in the air, they were perfect for aerial observation and escort for the convoys that crossed the U-boat-infested Atlantic.

|

|

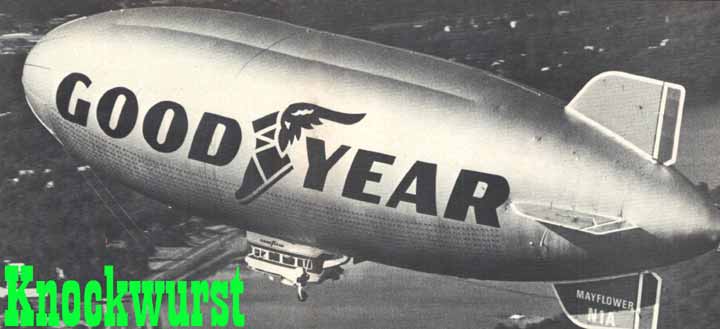

Flight deck on an airbag. The big wheel on the

right of the pilot's seat controls the pitch attitude and, with luck,

the throttles will drive it in that direction—more or less,

mostly less. |

Blimps like November One Alpha, more correctly called nonrigid airships, work on the same principle as undersea submersibles. They are weighted to neutral bouyancy so that, thermals notwithstanding, they will stay where you put them. They won't float up or down. The engines push the ship in the direction the nose is pointed, and the rudders and elevators make sure the nose is pointed where you want it. It's impossible to watch one fly without a new appreciation for the fact that you are standing at the bottom of an ocean of air. Watching a blimp floating by arouses the suspicion that there is a top and a bottom to this great fishpond of sky, and there could be somebody outside looking in.

Although basically the blimp is a helium-filled sausage skin, there are a few complications. For one thing, helium changes volume with temperature and atmospheric pressure, so not only does the blimp's buoyancy vary, but sometimes the helium can "shrink," which makes the outside skin wrinkle and look like a cucumber in a suit that doesn't fit. To compensate for the changes in atmospheric conditions, there are two airbags, one fore and one aft, that can be inflated or deflated to maintain a constant pressure on the outside skin. Each of these airbags has a scoop that picks up ram air from the propellers and a huge dump valve whose inventor's name must have been Rube. A simple piece of rope runs out to these valves, and as they are opened, they make a quiet, but embarrassing, sound.

Everybody has some bird he's always dreamed of flying—a P-51, or a biplane, or something semi-exotic with great emotional value. A blimp is not usually one of this category. In fact, I don't remember the last time I even thought about blimps, but the second I saw this one nosing around over North Jersey like a huge sea bass, I knew I had to figure a way to get a flight in it. Goodyear's public relations troops proved to be quite obliging, and I soon found myself cowering in the shade of N1A, ready to board.

The blimp is balanced to carry a full load of six people and be neutrally buoyant. When it carries less than a full load, the ground crew quickly adds or subtracts small 25-pound sand bags from a cubby hole in the side of the gondola. I always figured it would be bad public relations if a gal got off and saw that the crew considered her to be a six-bagger instead of a more petite four.

Naturally, a blimp isn't stable on the ground. What makes her stable is about 10 guys hanging onto ropes, holding her down, which can get pretty tense on a windy day. After I was sure everybody had a good grip, I scrambled aboard. My first thought was that there were no safety belts; my second was that I was in a Swiss cable car. It's all light and airy, the windows go all the way down, and the seats are half again normal size. It just doesn't feel as if you're supposed to go flying in it.

The controls themselves don't do a lot to strengthen the flying-machine image. The rudders are very high, and with your feet on them, your knees are flexed quite a bit, and your heels are six inches off the floor. Rudder travel is about a foot apiece, and as with kiddy car pedals, you expect to pedal to go faster.

There's not another thing between you and the panel—no stick, wheel-nothing. Since you don't have wings, you don't need ailerons, so there is nothing to control your roll. You just hang there beneath this big, ludicrous, silver thing. The elevators are controlled by a huge (really huge!) wooden rimmed wheel, about the size of a ship's tiller, mounted on the right side of the pilot's chair. You wheel it back and forth like a giant trim wheel for elevator control.

The panel has some things you'd expect and a lot that you wouldn't. It has manometers to keep track of the air and gas pressure in the fore and aft airbags, and it has enough instruments for a miniature weather station to keep track of atmospheric conditions. It even has weather radar, because at 35 mph you can't run away from anything. As a matter of fact, the pilots say that by the time something shows up on the radar, you're already in trouble. It's fully IFR equipped with dual glide slopes, marker beacons, transponder, and many other little goodies. Can you imagine reporting the outer marker and 15 minutes later having approach control calling you to ask how soon you expect to hit the middle marker'? Sitting under the pilot's left arm is a maze of levers. The two 210-hp Continentals are equipped with beta props so there have to be extra controls for them. I had often wondered how you put the brakes on a blimp; the reversible props explain it. As a kid, I used to think they just threw a big anchor out the back and tried to snag a house or something.

For takeoff, you pedal it into the wind, grab the elevator wheel with both hands and run it back a turn or two, giving it full throttle at the same time. The nose pivots up almost immediately, and the power nudges the ship along in the general direction of the nose. You're sitting there, the breeze coming in the open windows, leaning back in a ridiculous nose-high attitude, floating gently up and bobbing once in a while as it goes over a thermal. It's really different.

|

|

The 210 hp Continentals mostly just create noise

so people on the ground will look up and wonder what the hell is up there.

This time it was us. |

At altitude (1,000 feet), cruise power is set up and the airspeed surges ahead to 35 mph. It accelerates about as fast as a front porch and feels about the same. You keep the rudders in almost constant motion, thrashing in and out in an attempt to maintain a general heading. You're not really flying the ship, you're just suggesting a direction and hoping it agrees. Somehow, it seems that wind, updrafts, clouds, small birds, anything can do a better job of guiding it than the airship's own controls.

It was an extremely nice day to go flying, although floating turned out to be even better. The engines are behind you, so there isn't much noise, and you can shut them down if they bother you. With the windows open, you can lean out and see almost everything ... it's a very tranquil and nonmechanical feeling. We didn't worry about stalls and lift, or engines or fuel, or controlling, or anything. We just floated, looked, and enjoyed. It was so relaxing. As we descended for our landing approach, we crossed a golf course, so we leaned out the windows and shouted at the golfers below. They waved back. Imagine.

To land, the nose is pointed down, and the glide slope is maintained

with the nose and power. The one-point touchdown (the blimp only has one point)

was a Chaplinesque series of small, slow motion leaps, with the beta props coming

in to slow us down. The men jumped out to grab the ropes, and I felt like a

real aerial pioneer.

A blimp is a blimp is a blimp. It's a creature unto itself, a singular species

that bears resemblance to absolutely nothing and so can be compared with nothing.

Riding in one, you experience so few of the sensations we are accustomed to

that it doesn't even fit well under the heading "flying machine."

It's not really a machine, yet it is. It doesn't really fly, but it leaves the

ground. It's so completely unique that all you can say is, "It's different,

but it certainly is fun."

|

|

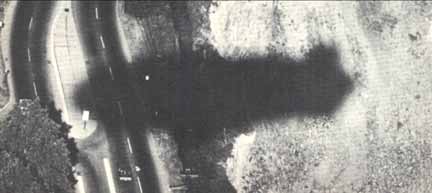

The sausage that almost ate New Jersey drifts

over some unspecting motorists on their way to work. |