Text & Photography by Budd Davisson, Sport Aviation, February, 1995

Berkut

Carbon Fiber Wolf Hunter

Text & Photography by Budd Davisson, Sport Aviation, February, 1995

Berkut

Carbon Fiber Wolf Hunter

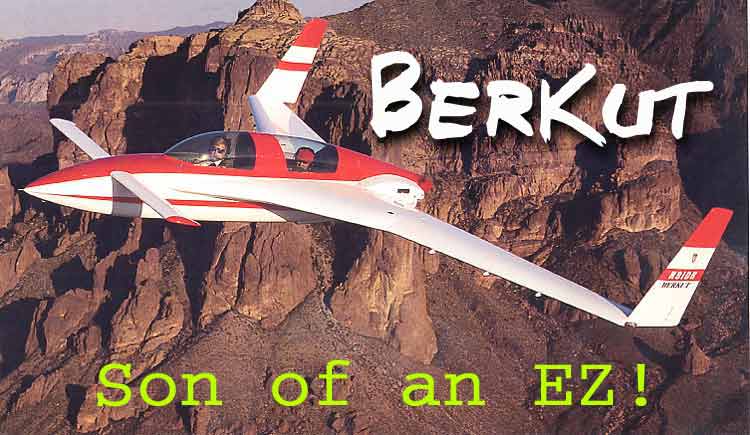

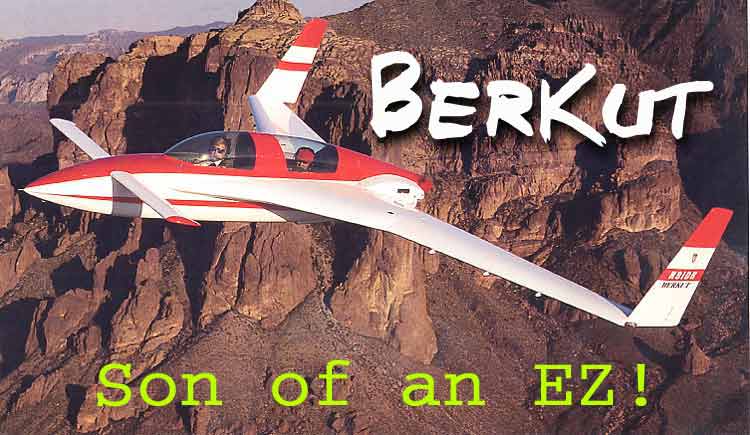

The descendants of the Mongols of central Asia must have an intense feeling of pleasure knowing they'd progressed to the point they could command the mighty golden eagle to do their wolf hunting for them. Their name for this ultimate bird of prey is Berkut.

'Wonder how they'd feel seeing their stately weapon swoop to the Earth backwards? Its tail feathers in front?

Those of us belonging to the tribe EAA wouldn't bat an eye at seeing a Berkut swoop down to the numbers with its traditional beak and tail pointing the wrong direction. That's how far we've progressed.

We now accept the unusual as the usual, courtesy of the sultan of weird, Burt Rutan. We have come so far since the original VariEze, 4EZ, blew us away at Oshkosh '77 with its absolutely Buck Rogers, this-can't-really-be-happening appearance, that nothing surprises us any longer. That is why an aircraft such as Dave Ronnenberg's wonderfully modern rendition of the feathered, Mongol wolf hunter is accepted as being only logical. It is part of a progression, a natural evolvement of the unique breed of eagles that look as if they fly backwards and are only a few steps removed from an picnic cooler in structural complexity.

Ronnenberg and his company, Experimental Aviation (3025 Airport Ave., Santa Monica, CA 90405, 310-391-8645 Editor's note: this company no longer is in business), have taken the basic concept of the VariEze/LongEZ and carried it to the next level. A long-time builder of LongEZs (eight to his credit), Ronnenberg didn't start out to have a career building backwards flying machines. He had been a serious model builder when, in his mid-twenties the death of his brother set him on a new life-path.

"That was the turning point of my life," he remembers, "I needed something to help me keep my sanity, so I decided to design and build an airplane of my own."

At that time he hadn't even been in a light airplane, but he felt he had to build something that flew.

"I don't know why I thought I could do it, but I had no reason to believe that I couldn't do it either. As a child I had always felt if I had the right tools and the right materials I could build anything."

He describes that first airplane as a cross between a Mustang and a Spitfire built of thin plywood and foam. Four years later he found the airplane had had its desired effect.

"At that point I realized I had survived the emotional upheaval of my brother's death and at the same time realized I had a natural feeling for fiberglass and composites. I looked at that airplane and knew I had done my kindergarten work at one end of it and my college thesis at the other.

"It had been a combination education and psychological survival course. it had served its purpose, so I took a saw to most of it and the only time it flew was as the parts left my hand and spun a few times before they hit the dirt at the Los Angeles dump."

|

|

|

|

The Berkut canopies probably add a lot of complexity and cost to the kit, but from my perspective they are worth every penny. The ability to taxi with one or both canopies open, ala F-4 Phantom, is worth its weight in AN hardware (or gold, which ever is higher). The usual canopy on a canard can't be opened during taxi although you can crack them to the safety notch on the latch. Taxiing the Berkut like a convertible was nice. Then, just reach up and pull, remembering to get the hands out of the way when it starts down.

Once the canopy was down, I found my forward seating position put the forward canopy combing in a position that blocked part of the top row of instruments including the airspeed. Again, adjustable pedals will solve that.

As we lined up on the centerline of the big Williams-Gateway 12R, I was conscious of a lot of pressure on the side stick from the elevator trim springs. Norm had said it was trimmed okay for takeoff, but there was no trim indicator so that was an educated guess.

The plan was to accelerate to 90 mph, smoothly rotate and climb out. With that in mind, I eased the power in, remembering I might need some brake to steer. It took only one tiny poke with the brakes before the rudders took over. Then it was just a matter of waiting a few seconds until the needle started towards 90 mph. I gently increased back pressure on the stick and found I was still fighting a lot of trim pressure. Norm had said the elevator would blow up to neutral and lighten the trim load. Apparently it needed the trim rolled further back because it took a lot of muscle to get the nose up.

When the nose cleared the runway, the airplane started off the ground and I went to check the nose and hold that exact attitude. When I did, the nose dropped far more than I wanted with the help of the trim springs and I skipped off the runway. Embarrassing! That was okay, though, because I'd embarrass myself much more later in the flight.

A quick fix for the trim problem would be a trim indicator, which could be nothing more than a paint stripe on the inboard end of a canard tip where the elevator mates.

Once off the ground I found holding the pitch attitude required some careful isometrics of me against the springs until I had enough sense to reach up with a thumb and toggle the lollipop trim switch on top the stick back a couple times. Then life became much more livable.

The airplane was moving around a little because I hadn't yet learned to appreciate how rapidly the airplane responded to any kind of aileron pressure. Any kind!

Retracting the gear was strictly a matter of throwing the small switch between my legs up. If the lights hadn't winked I would have never known anything had gone on, since the airplane didn't do anything unusual.

|

Norm's patient, reassuring voice in the Bose noise-canceling headsets (which really worked and are a necessity) told me anything over 100 mph was good for climb. I was doing a solid 110 before I pulled up into the climb and we started upstairs like a bullet. The literature says 2,000 fpm which looks about right, but the airplane felt much better the faster it went. The difference in actual climb rate between 110 mph and 140 mph wasn't enough to really notice, but the airplane seemed much happier and was much more stable at those speeds.

It is important you picture what flying something like the Berkut looks and feels like from inside the Raybans. For one thing, compared to most airplanes, you're practically laying on your back, which is, of course, an illusion. It's supine, but not very. The instrument panel is just above your knees gently caressing your Levi's and your legs are straight out in front of you. All rudder work is strictly from the ankles down. The legs never move. Glass wraps from just above your elbows, over your head and sweeps down to the top of the panel, giving the feeling the airplane stops just in front of the panel, since practically none of it can be seen. Although the canard is out there, it never occurs to you to look at it. It is mentally invisible.

The tiny throttle sticks up under your outstretched left arm and your right arm is slightly, only slightly, bent so your hand can wrap around the side stick. The trim switch is on top the stick, but a small square box on the side of it has a bunch of push buttons that flip-flop the comm and nav and let you talk to the outside world.

The movements required to control the airplane aren't movements at all. Especially in roll. The old saying about the airplane reading your mind absolutely applies here. In normal maneuvering, the stick doesn't move at all. Just the gentlest of pressures is all that's required to whip one wing down. The pressures required are so slight, sometimes its hard to tell whether you actually touched the stick or not.

The ailerons have absolutely no break-out forces. Nothing. None. Nada. They offer no resistance so centering the stick is strictly a visual affair because there is no small notch between pressure build-ups letting you know you've found center.

Furthering the feeling of mind-over-matter aviating is the tremendous roll response/acceleration right around neutral. Just the slightest pressure results in 5-10 degrees of bank instantly.

But, the illusion of whipping around the longitudinal axis is just that...an illusion. The actual roll rate isn't all that high and the aileron pressures required to get max rate are also far from being light, especially when measured against the response and pressures right around neutral. The pressures aren't linear.

This is just an analysis of the aileron feel, not a criticism. However, things happen very quickly right at neutral and it is no place for a ham handed pilot. The feel isn't that much different than a lot of canards, but the response is much higher, which is a welcome change.

The airplane also has yaw characteristics that are probably typical of highly swept wings. They give a huge amount of dihedral effect with yaw, so there is a definite coupling of roll with yaw. Swing the nose side ways with rudder and you get some definite roll with it.

The adverse yaw is also interesting. At cruise speeds adverse yaw is close to being non-existent. In fact, because of the roll-yaw couple, you're better off keeping your feet on the floor. Something I never did do very well.

At slow speeds, the airplane has a bunch of adverse yaw. Actually, at slow speeds it has what might be considered to be "normal" coordination requirements while at cruise speed it acts more like a jet.

Once trimmed out in level flight, the airplane just sits there requiring little or no input from the pilot. If upset by turbulence, however, the airplane takes a while to recover on its own. A few pitch stability tests showed the airplane to be statically positive, but not strongly so. Pulled 15 knots off cruise and released, it gently started back down and then surprised me by not over shooting the original speed by more than about 8 knots. It damped out completely with no long terms in two very leisurely cycles.

In setting up for cruise the aerobatic prop made itself known, however, the extreme effort for fuel efficiency also showed. At 2600 rpm, the electronic monitoring panel showed only 19.5 inches of manifold pressure! We were truing a shade under 180 knots (207 mph). Apparently Dave and his guys wind it up a lot faster, around 2800 rpm in cruise, but that seemed awfully fast to those of us used to normal looking numbers. With their earlier engine, which was slightly hot rodded, their speed tests showed 75% cruise to be about 208 knots true at 8,000 feet (1228 mile range, 10.3 gph) and the economy cruise was 187 knots (1514 mile range with 30 minute reserve, 7.7 gph). Race speeds which were officially recorded at various canard bashes ran between 240 mph and 248 mph. It would take a fast wolf to escape this Berkut.

The extreme stiffness of the airframe was very noticeable when cutting through turbulence. Since we were whistling along at over 200 mph and nothing in the airframe was flexing to absorb energy, even moderate chop hammered at us with sharp edges.

'Wondering about how I embarrassed myself the second time? The belly board speed brake is a T-shaped handle on the left side of the throttle. The mixture is a much smaller, but still vaguely T-shaped handle on the right side. Guess which one I pulled during slow speed tests for gear and speed brake effects? Like I said, embarrassing.

The gear speed is 150 mph, so it can be used to slow you down, but it really doesn't add that much drag and there is very little pitch change. It doesn't require retrimming at all. The belly board does pitch the nose down and does a lot for increasing speed stability when slow. If the power is up when the board is down there's a lot of buffeting from the prop working in dirty air but that all disappears when the throttle comes back.

The airplane takes some planning in approach just to get rid of the speed. Then it needs careful attention to keep the speed down. Norm wanted 100 on down wind and 90 down close to ground effect to leave enough canard authority in the bank to flair comfortably. Keeping it at 100 mph was a chore in the beginning, since just the tiniest nose pitch change gave an extra 10 mph. Once it got down to 90, it was much easier to control and was close to being speed stable at 85. In this respect, it was very canard-like.

The visibility over the nose is awesome on short approach. Also, once the airplane is slow with the speed brake out, it actually comes down at a much steeper angle than you'd expect for such a clean bird. Many canards need very flat approach angles. When the glide is broken it takes some concentration to keep from over rotating because the nose is so low it is almost out of sight. In fact, an attitude that looks to be nearly level is actually a good landing attitude.

Norm was intoning height above the runway as I willed the airplane down the last 5 feet. It was an interesting balancing act between me, the trim springs and an airplane that I knew would dart at the runway if I released any back pressure but would be all too happy to balloon if I increased angle of attack a fraction of a degree. I just kept working at it until the mains thumped on. The nose stayed in the air until I tried to gently lower it, at which time, it decided it had had enough and dropped to the ground as if relieved the flight was over.

Solid braking stopped us at the intersection and it showed no urge at all to do anything but roll straight ahead.

About that time I took my first breath since downwind.

Certainly one of the most asked questions about the Berkut is Ronnenberg's relationship with Burt Rutan.

Dave's response is, "When designing this airplane, there were several things I wanted to address and number one was I didn't want to anger Burt Rutan. He's a friend and we have conversations but we don't talk engineering, I don't ask for advise or help. He's keeping an arm's length relationship with me which I think is necessary.

"The airplane exists because of Burt, but only because he designed the airplane from which it evolved. But it evolved without his assistance. He was completely and totally separate. He had nothing to do with the program whatsoever and I think he'd like people to know that.

We didn't discuss the subject with Burt, but maybe we didn't have to. For one thing, the semi-finished Berkut in the Experimental Aviation booth at Oshkosh had the owner's name on it...Dick Rutan. Also, Ronnenberg recounted an incident at a past Rutan forum where Burt was saying he would never be involved in the sale of kits and plans again, but said something to the effect of, "...but if you'd like to see something I like, go see the Berkut..."

At this point in time there are nearly 50 kits in the field and Dave Ronnenburg expects at least three at Oshkosh 95. In the meantime, keep your wolves under cover. The Berkuts are coming.