Aerobatic

Musketeer

Aerobatic

Musketeer Aerobatic

Musketeer

Aerobatic

Musketeer

Text/Photography by Budd Davisson, September, 1970

Does the top of a radar blip look the same as the bottom? If a blip has a top and a bottom, I wonder what Wichita Center thought when they saw a blip over by Augusta doing four-point flip-flops and generally behaving like a waterbug. It's really weird to be squawking ident inverted!

The world needs another 140-mph, four-place airplane like it needs another navel, especially when it costs $20,000. What the world really needs is the perfect compromise-a cross-country chariot capable of going from here to there in great comfort, and still have a little spirit, a little romance. Most of general aviation's-wonder wagons have gadgets that'll make your lunch and hold your hand while guiding you down the glide slope. Most of general aviation's machines also have all the dash and inherent excitement of a '49 Buick Dynaflow. They're about as sporty as a fire hydrant. The Custom Musketeer is Beech's attempt at compromising, it's their contribution towards keeping fun in flying.

It's a curious notion, making a cross-country akro ship. At least it's unusual on this side of the Atlantic puddle. In Europe aerobatics isn't a dirty ten letter word and most of their ships have at least limited akro capabilities. It's only recently that aerobatics has gained respectability here. Any doubts of impending social acceptance for aerobatics should be quickly erased by knowing that Beech has a piece of the action. Beechcraft isn't known for an adventurous approach to aviation. They don't stick their neck out. They don't have to . . . they're hard-core Establishment and proud of it. The name Beechcraft whittled into the side of an airplane is, and has been, a guarantee of top quality, good performance, and predictable high prices ("It costs so little more to own the very best."), and they aren't going to play the aerobat game unless there's a stake that makes it worthwhile.

Basically the Musketeer is a trainer, and anywhere but in the hallowed halls of Beechcraft, the word "trainer" is another way of saying economy, expendable, small, simple, and cheap. These are words that Beechcraft doesn't even know how to pronounce, so their trainer popped out of it's aluminum womb, fully dressed in its Sunday threads and waving the Beechcraft banner like a VFW matron at a picnic. It was full grown, and a far cry from a cut-corner approach to training. If there is such a thing as too much of a good thing, the Musketeer was it. It was too elegant, too complicated, too big, and too expensive. The end result is that it runs a poor third to the 150 and Cherokee in actual numbers in use. It's not that it wasn't, or isn't a good trainer . . . it's too good. It's a silver plated hammer in a trade where the carpenters only need a garden variety Stanley or Plumb.

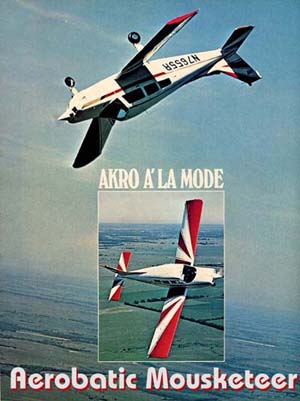

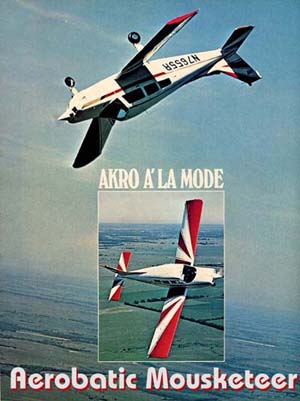

It's been two

years now since Beech took one of their Musketeer trainers, nailed

in a set of shoulder harnesses, a quick release door, splashed

on a sun-burst, and called it aerobatic, but 1970 may be the year

that it really makes the grade. Not much has been done to the

1970 Musketeer to set it apart from its predecessor. Some interior

appointments, a few nuts and bolts here and there, but the major

change has been in the marketing department's approach to it.

In the past the Akro Musketeer has been the bottom of a mighty

tall totem pole, but the fantastic growth in sports aviation has

been noticed by even the stuffiest of executives, and they've

decided to give the runt of the Beechcraft litter a higher priority

and help push it on it's way. The job of head Musketeer pusher

falls to Bob Beutgenbach, who was my host during my brief, but

exciting sojourn in Beechcraft country.

It's been two

years now since Beech took one of their Musketeer trainers, nailed

in a set of shoulder harnesses, a quick release door, splashed

on a sun-burst, and called it aerobatic, but 1970 may be the year

that it really makes the grade. Not much has been done to the

1970 Musketeer to set it apart from its predecessor. Some interior

appointments, a few nuts and bolts here and there, but the major

change has been in the marketing department's approach to it.

In the past the Akro Musketeer has been the bottom of a mighty

tall totem pole, but the fantastic growth in sports aviation has

been noticed by even the stuffiest of executives, and they've

decided to give the runt of the Beechcraft litter a higher priority

and help push it on it's way. The job of head Musketeer pusher

falls to Bob Beutgenbach, who was my host during my brief, but

exciting sojourn in Beechcraft country.

Bob gave me a short rundown on the Musketeer and its construction. Very little had to be changed or beefed up to make the akro version strong enough to take the push and pull of aerobatics and qualify it to aerobatic category. The center-section combines steel tube and stressed skin, and the original design was more than strong enough, which says a lot for Beech design philosophy.

I had never flown, or even looked at, a Musketeer in my life, and several things surprised me. The first was the size of the ailerons-they're huge! I checked a normal Musketeer and found they all have the same big flippers. It's a characteristic of the breed. Also, I guess I'd never noticed that it had a stabilator instead of a regular stabilizer/elevator. It was going to be interesting to see how the stabilator reacted in aerobatics.

Walking around the bird we checked for anything that might fall off once we started twisting her tail. Since we were going to ask a lot more of her than a level X-C, we were particularly careful looking over the tail and motor mounts. The tail fittings are just a little hard to see, and the new fiberglass cowl makes inspecting motor mounts a chore too. This was a Custom Aerobatic Musketeer, which means it has a 180-hp Lycoming to drag it around, rather than the usual 150-hp.

As low winged airplanes go, the Musketeer is quite easy to mount. The door is big enough to be ridiculous, and there is no need to swing in while grasping the cabin top, ala P-51, nor is there any reason to crawl in head first and turn around like a puppy fluffing up his blanket.

The shoulder

harnesses pivot through a fitting on the cabin roof behind the

occupants' heads, and are designed more for holding you back;

than down. I much prefer the old military type that have nearly

a 90 degree angle over the shoulders, so that they crush you into

the seat, if you pull them too tight. The Musketeer won't run

inverted, but if they ever modify it so it can run around on it's

back, I hope they change the harness accordingly. A good set of

shoulder harnesses makes all inverted maneuvers a lot more fun.

The shoulder

harnesses pivot through a fitting on the cabin roof behind the

occupants' heads, and are designed more for holding you back;

than down. I much prefer the old military type that have nearly

a 90 degree angle over the shoulders, so that they crush you into

the seat, if you pull them too tight. The Musketeer won't run

inverted, but if they ever modify it so it can run around on it's

back, I hope they change the harness accordingly. A good set of

shoulder harnesses makes all inverted maneuvers a lot more fun.

Beech also depends on one seat belt to keep your noggin off the headliner. Almost all the aerobatics the Musketeer is approved for can be done without a seat belt, if they're done right, because they are all positive G maneuvers, but I doubt if there is an aerobatic neophyte living that hasn't pushed too hard in a roll and slammed himself up against the seat belt. For that reason, I'd also like to see either two belts, or a big hairy military type. The big belt should be there to help cover up mistakes.

As soon as you fire it up, the first thing you notice is the vertical tachometer presentation. A little pointer runs up and own a column of numbers similar to some automotive speedometers of a few years back. It doesn't take long to get used to, but it fouls you up when you glance at it for a quick reading.

Takeoff and climb are completely normal because the bird is a basic airplane and flies like one. Nothing exotic or demanding. It breaks ground with very little urging from the control column and climbs out at a respectable 1,000-fpm. The immediate feeling I noticed was one of solid comfort. Everything is in the right place, the seats feel great, the panel is plushness personified, and the rams-horn wheels feel like they were custom molded to my hand. It's so much easier to control an airplane when you feel at home in it, and we weren't ten feet off the ground before I felt that way. I couldn't get over the feeling of the control wheels. I guess I'm overly sensitive to the way they fit, but since that's your primary contact with the airplane, it should be as natural as possible. The wheels are sculptured so that they bulge where your hand is hollow and shrink where your hand is full, and a small, well shaped protrusion supports your thumb. It feels very much like the grips on an Olympic-type target pistol.

I was immediately surprised at how the controls themselves felt. Just standing back and looking at a Musketeer you'd think it would be a slightly Dumbo feeling Detroit-like airplane, but it's not. The ailerons are unbelievably smooth and extremely light for this type of airplane. They don't rate with Zlins or Jungmeisters, but they are better than the Cardinal's, and the Cardinal's are good.

As soon as we got out to the practice area, I pulled a few tight 360s, clearing the area and looking for company. Finding none, I rolled out over a road, pulling the nose gently up to a 30 degree pitch attitude, slowly rolling her over on her back, bleeding off airspeed so I'd be slow enough to do a split-S. As the horizon leveled out upside down, I let the nose fall and the speed build, pulling up into one of the smoothest aileron rolls I've ever done. It wasn't me that was smooth, it was the airplane. At 140-mph and 20 degrees nose high, those big, fat ailerons reach out and effortlessly ease the airplane around its longitudinal axis. Even though I feel awkward (and illegal) doing aerobatics with a wheel, the control wheel travel didn't bother me at all. Most other aerobatic ships with wheels demand that you practically wring their neck to make it go around, but the Musketeer whips right around with less than 90 degree wheel deflection. I didn't care what else it did, or how well, because rolls were definitely going to be its strong point.

Bob told me

to loop it from about 150-mph and use a two and a half G entry.

I dropped the nose and had 150-mph instantly, it picks up speed

pronto (just like a Beechcraft), and hauled back on the wheel.

As the wheel comes back, the stick (oops, wheel) forces get higher

and higher. The wing pivoted around the horizon like it was supposed

to, and when I saw the ground again, I eased off the power and

checked the G meter. Two Gs! I did it again, this time using two

hands, and finally got the recommended two and a half on the G

meter. The servo tab (the small surface running across the trailing

edge of the horizontal tail) is there to add resistance, because

a stabilator has none of its own and it would be possible for

a pilot to over control it. The servo tab gives the pilot more

of a feel of what he's doing . . . the more he deflects the stabilator,

the more the servo tab resists. I think they are going to have

to change the servo tab linkage to reduce its movement because

I was one pooped pilot, after fighting the servo tab through a

few loops.

Bob told me

to loop it from about 150-mph and use a two and a half G entry.

I dropped the nose and had 150-mph instantly, it picks up speed

pronto (just like a Beechcraft), and hauled back on the wheel.

As the wheel comes back, the stick (oops, wheel) forces get higher

and higher. The wing pivoted around the horizon like it was supposed

to, and when I saw the ground again, I eased off the power and

checked the G meter. Two Gs! I did it again, this time using two

hands, and finally got the recommended two and a half on the G

meter. The servo tab (the small surface running across the trailing

edge of the horizontal tail) is there to add resistance, because

a stabilator has none of its own and it would be possible for

a pilot to over control it. The servo tab gives the pilot more

of a feel of what he's doing . . . the more he deflects the stabilator,

the more the servo tab resists. I think they are going to have

to change the servo tab linkage to reduce its movement because

I was one pooped pilot, after fighting the servo tab through a

few loops.

It snaps like crazy! The first one caught me with my britches down and I recovered a quarter turn too late. The entries aren't really sharp unless you use aileron with the back stick, then it leaps around and you have to lead recovery a good bit. I was really surprised. I think I expected it to snap like a Greyhound bus.

I never did get a really good immelmann. For some reason or other it always runs out of steam just as you start to roll out inverted. At first I thought it wasn't enough speed, so 1 used a higher entry speed, which helped, but they still weren't clean. By doing a half snap on top, it would do really crisp ones, but they still weren't correct. I've no doubt that practice would produce good immelmanns, but we didn't have the time.

At least one other stabilator equipped trainer exhibits a dangerous spin characteristic in that it doesn't have enough elevator to hold it stalled in the spin. The result is that after a turn or so, it translates into a tight spiral, with no change in attitude and no warning other than a skyrocketing airspeed. Several times I spun the Musketeer through three turns, and found that as long as you bear-hugged the control column to your chest and kept it all the way back it did a completely normal spin. It was going around fast as blazes, but it was still normal. If you relaxed on the wheel one tiny bit, the airspeed would start up and you were in a graveyard spiral instead of a spin. When that happens, in a Musketeer or anything else, you'd better recover quick because red line is only a second or two away and the ground is just a little ways past that.

Before we headed back to the barn, l did a clover leaf and found to my surprise that it lost no altitude. To any of you deprived individuals who don't do aerobatics, a clover leaf is four loops, back to back, but you do a quarter vertical roll in the entry to each of them, which means each loop starts over the same point, but is ninety degrees to the last one. I'd pull the nose up until the wing was at right angles to the horizon, roll until the wing sat on a point ninety degrees from where I started, and pull it over into a loop. It's a fun maneuver to do and the Musketeer does it as well as any aerobatic trainer I've ever been in, and better than most.

Aerobatically speaking, the Akro Musketeer is quite a good airplane, it's surprisingly good. As a trainer it might have a few minor drawbacks, the biggest of which is the fact that it will pick up speed like the proverbial greased crowbar. It looks like the instructor would have to really ride herd on his students during the first couple rolls, and such, to make sure he doesn't accidentally split-S out. If you let this thing run downhill for just a second, inverted, it'd hit red line faster than you can think about it. On the other hand, it rolls so nicely it should be no problem teaching even the most club-footed student rolling recoveries. I think I'd work on unusual attitude recovery pretty early in a student's aerobatic career to keep him out of trouble, which is smart in any airplane.

As a plaything, the Aerobatic Custom Musketeer is expensive, no doubt about it. As a cross-country tool, however, it's not bad, and its 140-mph plus cruise makes it mighty useful. It's plush, it's comfortable, it's sexy, and it can do rolls, which makes it positively groovy. Aerobatics is the other half of flying, it's the half that completes your training as a pilot, and makes you a real flyer instead of a driver. Unfortunately, in the past it took one type of airplane to do the right side up half, and another type to do the wrong side up part. I think it's darned considerate of Beechcraft to come up with one airplane that's good at both, the Aerobatic Custom Musketeer 1970.