If I live to be 30 (

Ed: I was a real

smart ass at that age!), I'll never forget the feeling sitting at

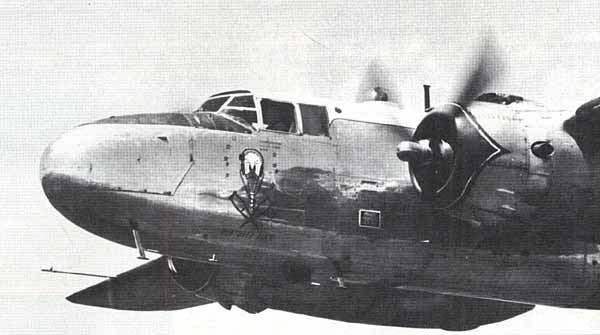

the end of the runway, right hand wrapped around two throttles, looking

out at 3,600 horses in two big radial engines. The 22,000 pounds of airplane

around me agitated gently but noisily in their wake. Now I know how George

Plimpton felt facing Green Bay, but at least he could lie down and play

dead-I wouldn't be playing. I was about to fly the big, beautiful B-25

bomber!

At that moment I just wasn't geared toward bombers. Fighters, maybe, or

aerobatics, or homebuilts. But big, hulking, roaring bombers-definitely

not.

Prepared or not, I suddenly found myself in the left seat of N543VT, a

North American B-25N, Mitchell. junior Burchinal, proprietor of Flying

Tigers Air Museum, was in the right seat, shouting at me to do this and

that. Yes, I'm multi-engine rated, but most of my limited experience has

been in a couple of moth-eaten Apaches, and the B-25 bears as much resemblance

to an Apache as I do to Raquel Welch. Ninety percent of my flying is done

with only stick, throttle, and rudders to worry about-no boost pumps,

feathering systems, emergency gear extension, bleed hole icing, Vmc, constant-speed

props. Now I had to think about shimmy dampers, exhaust stacks, oil coolers,

hydraulic accumulators, and brake pressures.

| |

|

| |

Burchinal's B-25, if seen on the line

today, would be viewed as a really tired looking old airplane

because it had never been restored, as is the case with every

B-25 today. In 1971, when this was written, there were dozens

of them around in "still flying but roachy" condition

and no one wanted them. None had been restored yet. |

Flying a 10-ton aluminum ingot isn't something you just wander out

to your local FBO and do. In any case, I was going through the World

War II flight course at the Flying Tiger Air Museum in Paris, Texas.

My original intent was to fly the fighters, but the B-25 is also part

of the program, intended to broaden your education—and it does,

in spades! Heavy in this case means about 17,000 pounds empty, with

an allowable emergency overload of nearly 45,000 pounds. That's more

than my hometown weighs!

This particular Mitchell probably would be more correctly termed a VB-25N,

since it originally was an executive transport for the RCAF. Most B-25s

don't have dual controls, but this one, along with many of the TB-25s

still flying, is completely set up for two pilots, as a training ship.

Originally, I was to go up with junior and drive the 25 around for an

hour or so, just to see how it felt. I began to like the idea of flying

the big moose, however, and I soon heard myself saying things about

"more time" and the words "type rating" kept popping

up. Type rating! That's the special license it takes to carry passengers

in airplanes that weigh more than 12,500 pounds, and the B-25 weighs

that much with one wing and both engines removed. It takes a different

type rating for each type of airplane. The change in program meant I

would have to learn the airplane inside and out, and that's a lot of

territory. Burchinal is a FAA-designated examiner for the B-25, and

I knew he would be tough.

My first "introductory" flight made me feel like crawling

into the bomb bay and going for a walk outside. I thought the Mustang

was a departure from the Citabria; the B-25 is in another world entirely.

When we got up into the air and over the practice area, Junior signaled

for me to take it. I took the wheel, and a slight out-of-trim condition

caused the nose to drop. I automatically pulled the nose up—or

at least I tried. I was flying with my left hand, my right resting lightly

on the throttles. I could hardly pull the wheel back with one hand!

I released the throttles and brought the other hand over to help, barely

getting the nose up level. I finally had enough sense to wheel in some

up trim. The controls couldn't be that heavy! I made a turn to the left,

or at least my hand did, but the control wheel resisted my attempts

to move it. Grasping it firmly, determined to do it with one hand, I

forced one end down, and the wings responded smartly enough by rolling

obediently into a left bank-then the nose started to fall. With the

30-degree bank I was holding, I had to force the wheel to the rear to

keep the nose from falling. It had started losing altitude the second

I started to roll. I wasn't prepared for the heavy control pressures.

Just to prove to me that the airplane would fly, junior reached up and

punched a red button on the console between us that started moving levers.

As I was watching him, I saw the right propeller come to a stop, its

blades edged into the wind. He diddled with some trim wheels and sat

there, hands off, boring along with only one engine going. Satisfied

that I had been suitably impressed, he fired up the other engine and

headed back to his field.

I expected a long approach, nose high, with lots of power, dragging

it in over the wires and stomping on the brakes to get stopped. He aimed

the nose at the runway and I figured we were going to make a high speed

pass. When we were over the middle of the runway at about 200 knots

indicated, he pulled up hard to the left in a tight chandelle. While

he was doing this, he started scurrying around the cockpit, throwing

this and yanking that. Suddenly, I realized he was doing a 360-degree

overhead approach, fighter style, right off the deck in a B-25. At the

top of the chandelle, we were downwind opposite the end of the runway.

He brought the throttles back, turned into the field and beautifully

completed the 360-degree turn as he plunked us down on the runway. The

man certainly knows his airplane.

I knew I had my work cut out for me, so I started memorizing systems

and going through the preflight checklists. When all the gizmos and

gadgets are explained, you find there aren't that many things that are

drastically different from what you're used to. It's still an airplane,

and you must check the oil and gas, the struts and tires, the controls

and so forth.

The B-25 does have several particulars that we little-airplane drivers

don't see often and that must be checked. For one, the shimmy damper

has a little nubbin, a small rod for all practical purposes, that sticks

out of the top. If it doesn't stick out at least three-eighths of an

inch, you don't fly. On airplanes as big as the 25, if the shimmy damper

fails, it can destroy the airplane. Junior told me about a Mitchell

he saw that lost the damper on landing roll-out: it sheared rivets and

buckled sheets back into the wings, completely wrecking it. He lost

one on the B-26 while taxiing into a parking place, and in the time

it took to roll 10 feet all the Plexiglas was shaken out of the nose.

Just below the shimmy damper is a knurled cap screwed on to a bolt-like

affair that goes through the strut. Under the cap is a pin that can

be pulled out, allowing the nose strut to turn freely for towing. The

cap has to be finger tight. You really have to depend on the half-inch-thick

book that makes up the preflight checklist.

| |

|

| |

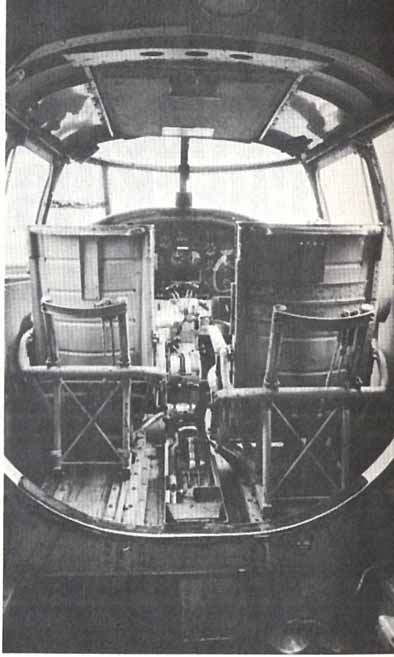

The view from just behind the top turret

position ahead of the bomb bay bulkhead. At the bottom, under

the curved frame, is a short ladder that goes to the hatch on

the bottom of the airplane. |

You enter the flight deck through a hinged hatch that contains a ladder,

located in the belly of the airplane, about in line with the propellers.

When you climb up, you find yourself standing in a small room, about

six feet square, going from the top to the bottom of the fuselage. It

has a couple of jump seats and a Plexiglas bubble in the top for navigation

work. The forward side of this area is only about three feet high, opening

into the back of the cockpit.

Getting up into the pilot's seat is a major operation. The cabin roof

is fairly low and the seats are close together, which means you have

to walk on the row of knobs and levers that cover the space on the floor

between the seats.

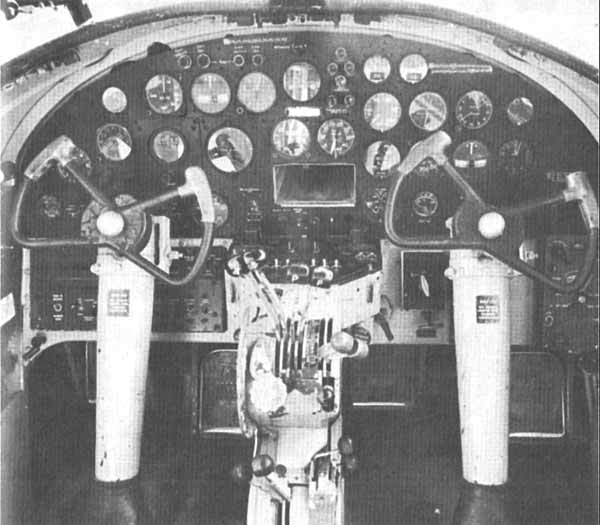

The instrument panel isn't nearly as complex as would be expected. It's

actually simpler than in many light twins. Some of the instrument placement

is rather odd, and every available inch of side panel is covered with

emergency system controls.

The throttles, props, and mixtures are where you'd expect them to be,

and most of the rest of the switches for starting, fuel management,

and feathering are on the trapezoidal-shaped panel just in front of

the throttles. The props are feathered by depressing the appropriate

large red button on this panel. The Ham-Standards feather in less than

10 seconds and unfeather in about twice that time. Since feathering

is by electrically driven pumps, it's a good idea to check the generator

panel on the right side of the cockpit to make sure both generators

are working, or if one is out, that you don't feather the engine with

the good generator.

I must have spent at least eight hours sitting in the airplane running

through emergency procedures and making imaginary touch and goes. Since

I'm not used to handling any kind of procedure at all, it took some

effort even to remember to bring the gear up, or push the props up on

final. I spent so much time in there and would get myself so wound up

psychologically flying patterns in my mind, that I’d get the adrenaline

pumping and one leg would be twitching uncontrollably. Yeah, I was just

a little hyped!

On my second hop we did stalls and all the other exercises that go into

learning an airplane's bad habits.

Satisfied that we had enough altitude and there was no traffic around,

I started reducing power and bringing the nose up, feeling for the stall.

I thought an airplane this big would flop on the ground, tail first,

when you stalled it nose high, but I was pleasantly surprised. We were

light, so the stall didn't show up until we were way down around 70

knots. When it broke, there was no mistaking it, but it wasn't as violent

as in many modern twins. It jumped once, dropping the nose through the

horizon, and rolled left slightly. Keeping the nose down and adding

power, we had flying speed in less than a thousand feet, losing no more

than 1,200 feet, and I had been slow adding power. The only hard part

was the physical exertion involved. As the airplane slowed down and

the sink rate went past the peg, the controls lost some of their effectiveness,

calling for bigger control deflections, which meant more arm muscle.

| |

|

| |

The panel itself is pretty straight forward

but the console has a herd of levers, switches and buttons that

have to be deciphered. The big control yoke is right against your

chest during flair and the runway disappears behind the nose.

|

Single-engine drills in the B-25 are really fun (spoken sarcastically).

One thing is certain: when an engine shuts down, there is no doubt which

is the "idle foot." My good foot was working so hard that

after each hop it took several hours for my knees to stop shaking. During

my multi-engine training, I remember seeing an engine feathered just

once; that's all the FAA requires. Burchinal feathered one everywhere

except at the gas pump. There are only two things to remember when feathering

a B-25; remember what the Vmc is for your weight, and move your fanny

forward in the seat because you have to be seven feet tall for your

legs to push the rudder all the way down. I found myself wedging my

shoulder against the seat and practically standing on the rudder, lying

sideways in the seat, right hand frantically cranking in rudder trim

located at the base of the control console. Once the trim is in, the

airplane is a pussycat, but if you don't start cranking trim right off

the bat, the pussycat will eat one leg, and maybe your entire lunch.

The handbook says the minimum single-engine control speed at 27,000

pounds is an incredible 126 knots (145 mph). We investigated Vmc and

found that at our reduced weight of around 22,000 pounds we could fly

it right down to 80 knots indicated and still hold the nose straight.

Doing single-engine stalls, I got very good at leaping on that power

and bringing it back quickly. You forget to reduce power only once in

a power-on, stalled, engine-out situation, then the B-25 does all the

talking and you do the listening.

For my first landing, we flew a wide downwind at 120 knots and I ran

through the landing check as fast as I could because the airport was

disappearing rapidly. Burchinal played co-pilot. I called for the gear

and at the same time pushed the props up to 2200 rpm, where they would

stay until we were on the ground. Mixture went to auto-rich and boost

pumps went first to low, then high. By this time I was way past the

airport, so I brought the power back a little and started a turn on

to base. The second I started the turn, I knew what junior had been

talking about when he mentioned heavy aircraft and the way they need

power and don't need steep banks. When the wing went down, the airplane

started sinking immediately and I had to advance power to catch it.

Not even in the Mustang did I have this feeling of being behind the

airplane, of being rushed.

On base, I found myself using a lot of power just to maintain status

quo, cranking in trim every few seconds. I stuck up two fingers, indicating

to Burchinal I wanted half flaps, adding more power and trim. As I turned

final, I stuck up four fingers for full flaps and started gently reducing

power and struggling with the nose to get 110 over the fence. Then I

had 110 knots and Burchinal was yelling to bring the B-25 power back.

I thought he was crazy, that we'd never make the runway, but I killed

the power anyway, keeping my nose pointed at the numbers, 110 knots

on the gauge.

| |

|

| |

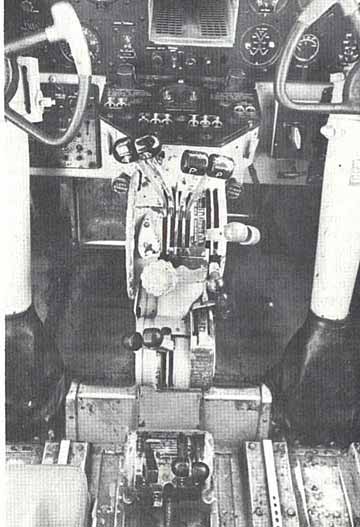

The flat top of the console has all the

engine control stuff on it including the fuel boost and starter

switches. The big knobs on the two forward corners are the red

"feather" buttons for the props. At the bottom of the

console on the floor is the landing gear lever. |

I started bringing the nose up and Burchinal started yelling "Pull,

pull!" He grabbed the wheel and helped me. It turned out I was

flaring in the right place, but I would have touched down on all three,

or just a little nose high, but I would have been too hot. Burchinal

kept me pulling and we touched down with the nose in an impossibly steep

nose-high attitude, completely hiding the runway.

Roll-out was arrow straight and Junior cautioned me to be very, very

gentle on the brakes, because they are sensitive. My toes crept up on

the top of the rudder pedals and pushed as gently as they could. Jerk!

And the nose strut compressed as I nearly locked the brakes. They have

double discs and just need a whisper of pressure to stop the wheel.

Trying to taxi smoothly was a near impossibility.

Once we were on the taxiway, junior started telling me to call for what

I wanted, meaning flaps up, cowl flaps open, and boost pumps off. I

proved once and for all how calm and cool I was: In my gruffest, most

professional voice, I called out, "Gear up!" It just wasn't

my day.

Takeoffs are really, really exciting-possibly even more so than in the

Mustang, because you know the tricycle gear will take care of the takeoff

roll and you have more time to bask in the glory of flying a bomber.

In the Mustang, I was always a little too busy for sight-seeing. After

making sure that everything on the quadrant was full forward and the

boost pumps were on, I'd call for one-quarter flaps and start the throttles

forward. As soon as the airplane is moving, the rudders are effective

and you only have to touch the brakes just once before the rudders come

in. The power must come up slowly to keep the prop governors from surging

and you have to monitor manifold pressure to keep it under 44 inches.

Considering the amount of airplane around you, the acceleration is fantastic

and the noise is even more so. There are different kinds of noise. In

the Mustang, it was almost unbearable. In the B-25, it was just as loud,

but it didn't seem to bother me. It was like the difference between

a rifle and a shotgun. The Merlin in the Mustang cracked and barked,

but the R-2600s in the Mitchell roared like a tired lion, and had a

softer, less harsh noise.

Since I knew Vmc was 80 knots, I picked the nose up at 80 knots and

let the airplane run on the mains until it indicated 100 knots, lifting

it off and calling for, or grabbing, the gear as soon as possible. On

my second takeoff, as soon as we broke ground and I had yanked the gear

up, Junior nonchalantly caged the right engine. Aside from a few frantic

moments and a foot that was turning purple, the B-25 climbed out as

if it didn't even know half its engines were out.

On the type-rating check ride, Junior tossed a single-engine landing

and a single-engine go-round into the same hour. Junior has a knack

of working you right up to the edge of your talent, forcing you to learn

as you go.

The single-engine landing was really interesting because we were five

miles from the field when he punched it out. This meant I was going

to have to drive it in, play with all those levers, fight the airplane,

and land it as well. At first, I tried to figure out how much power

it was going to take to keep us up with the gear down and half flaps,

and then I remembered that I didn't dare put the gear down until I had

the runway made. The airplane won't fly with only one engine and the

gear hanging out.

Finally, I was on final, keeping it high just in case, waiting until

the last second to drop the gear, remembering it would take longer to

extend with just one hydraulic pump working. As soon as the gear started

out and I reduced power to let the airplane down, it became just another

of those pull, pull, pull kind of landings. It took nearly four hours

in the B-25 before I got used to pulling so hard and getting the nose

so high.

(Editor’s Note: You’re going to just love the next paragraph!

Things have definitely changed since 1971) Pound for pound, B-25s are

the cheapest flying machines in the business. You can buy ex-military

jobs all day for $5,000 and superplush executive conversions never run

over $10,000, usually averaging around $7,500, complete with lavatories,

bunks, and your own private bar. They're just the thing to put you in

competition with Hugh Hefner's DC-9. They are fast, easy to fly, fairly

forgiving, just oozing with romance, and give you instantaneous he-man

status. They cruise at an effortless 200 to 220 mph and can top most

weather. Then why don't more people want them? It's because of the Wright

R2600s. At today's prices, it costs over $500 to fill the Mitchell's

1,000-gallon tanks (Ed: now that’s funny!) and that gives

you less than five hours of flying fun. About the leanest you can run

it is 120 to 140 gallons per hour; closer to 160 gph, if you're going

somewhere. It's not exactly the airplane for Sunday afternoon puddlejumping,

but it grows on you, like a big, friendly dog. Too bad we can't afford

to have one as a house pet.

B-25's and "Catch

22"

When they made the movie of Joseph Heller's slightly off-center

anti-war movie, they unwittingly saved the lives of the majority

of B-25's still flying today. Frank Tallman and company was task

with coming up with something like 25 flying B-25's and, in so

doing, resurrected a bunch of derelicts that had only a few years

left before becoming beer cans. The movie is worth seeing if nothing

else to watch mass takeoffs of Mitchells from the dusty strip

they hacked out of the Mexican desert.

|

Mitchell Shopping

Although Mitchells have recently become the darlings of the restore-it-totally-accurately

crowd and millions (literally) have been spent tracking down and

installing every little bit of military hardware, the airplanes

are still reasonably (by warbird standards) priced. It's seldom

you see one over $500,000 and lots are down around $300,000. However,

there are some that haven't had the center section rebuilt, and

that's where corrosion loves to hide, so it's usually smarter

to pay more for a better airplane.

|