Text and Photos by Budd Davisson, Air Progress, May , 1981

Tinker Toy Taperwing for

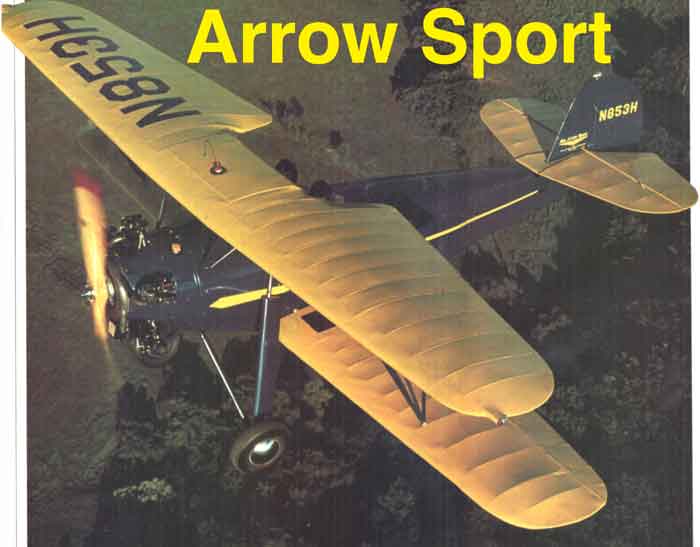

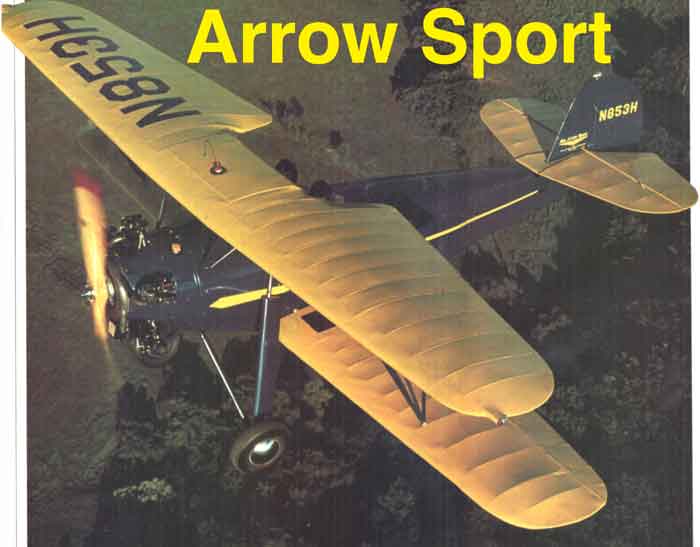

Two: the 1929 Arrow Sport |

From 3,000 feet, time seems to stand still in a lot of America. The Rockies haven't changed since man first scaled them and the Mojave still stretches on to the horizon. In the Mid west, the green and black patchwork of loam and wheat or corn, sorghum or milo is as it was fifty years ago. If you were to fly a straight line through Nebraska, say from Lincoln to Cozad, you'd find little has changed. Oh yeah, all of Highway 34 is paved now and the concrete of Interstate 80 slashes across the landscape on its way to Boulder. But otherwise, man's hand hasn't made any marked mutation of the land that differs from the patterns of half a century ago. Things have, however changed in the skies over Nebraska. Fifty years ago in Lincoln the skies were alive with Lincoln's own aeronautical products. The Arrow plant in the suburb of Havelock was busy cranking out various designs, including one that eventually used a converted Ford V8 that was certified. Right on the north edge of Havelock there were two airports, Arrow and Union. The young Lindbergh was supposed to have started flying at Union (it was actually in a farm flying field just to the north of it, where the Rt 77 exit ramp cuts off of Interstate 80). The other field the old Bill Kite operation was where most of Havelock's aeronautical hardware first took to the air. All variations of birds from the big Lincoln-Page biplane to the V-8 powered Arrow flitted off the runways that are now rapidly disappearing under urban sprawl. So, yes, a few things do change. Both Union and Arrow are gone. A railroad track cuts right through the middle of Union while Arrow is about to become a housing project. The good news, however, is that west a ways, about 150 miles as the biplane flies, a bit of the Lincoln/Havelock heritage lives on. Out at Cozad, an archetypical farming community that straddles the border between the rich farming belt of eastern Nebraska and the semi-arid sand hills ranching area, Jim Marshall rides herd on one of the six or seven remaining Arrow Sports.

The Nebraska aviation scene is a story unto itself, but in 1927, when the plans for the Arrow Sport were drawn up, Lincoln was a very busy place. In point of actual fact, the only reason Wichita eventually became the seat of Midwestern aviation is because they had a more active group of community businessmen supporting their aviation activities. The Arrow Sport answered a need at the time for a smaller, low-powered biplane that could be used for training as well as occasional cross country. Sven Swain, the designer of the Kari-Keen and Inland Sport, laid down his lofting lines and the first Arrow Sport was built about 1928, but its success was hardly immediate. The original used a puny little sixty hp LeBlond, and must have been a real ground hugger with two people on board. However, at least a couple of these have survived to this day. It wasn't long before the 100 hp Kinner became the standard rubber band for the Arrow Sport, much to the relief of instructors of the period.

From a purely personal point of view, I've always thought the Arrow Sport would make a super little homebuilt. It's about the right size with a twenty-five foot span, although it is a little heavy at 1,000 pounds empty. A lot of that weight is in the 100 hp Kinner and some more is in the wing structure. The wings are, for all intents and purposes, cantilevered units ... they don't need struts or wires. To do that, of course, demands railroad-tie spars and lots of anti-torque, antidrag bracing internally. But it's the wings, the fantastically beautiful tapered wings that make the Arrow Sport what it is. If you changed the planform by a millimeter in any direction you would blow it. You could re-engineer the structure and lighten it considerably by using interplane wires or a strut. And you could put a 150/180 Lycoming up front and the proper cowling - maybe an open-cheek affair like a J-3's - wouldn't detract too terribly from the appearance. But, you couldn't mess with the shape of the wings!

In all honesty, Marshall's airplane was only the third Arrow Sport I had ever seen, right after Talmadge's on Long Island and the one hanging in the Lincoln, Nebraska, airline terminal. Marshall's furthermore, was the only one whose owner offered me a chance to fly it, so I perked up and paid a little more attention to this one. Standing next to it, you realize that has to be one of the smallest antiques around. The top wing is barely head high and the cockpit coaming is almost low enough to sit on. Nearly every fitting in the airplane, especially those holding the tail in place, are in plain sight and directly in the airstream. The size of the fittings bespoke massive strength as well as sizeable drag coefficients. In spite of its over all cuteness and lack of flying wires, I knew this thing was going to have its share of drag. The cockpit appears either large or small for the airplane, depending on whether you are viewing it as a one place or a two place. It is supposed to be a two place, and even has dual throttles, but before climbing in, you know it's going to be a tight fit. It's one of those airplanes in which you develop a very close relationship (shared patches of sweat where you touch) with your passenger. When I climbed in with Jim, my thoughts about the cockpit confines came true. We both fit in there like the correct pieces of a jigsaw puzzle, neither one of which rattled around in its slot. One pleasing surprise was, the visibility… it was great for an antique. It was so good because I stuck far enough out of the cockpit that the top of my head was sticking over the windshield. With minor stretching, I could nearly see over the top cylinder of the Kinner. Since I was sitting on the right side (I put Jim where he had brakes to keep us out of the bushes, a wise move I found later), the throttle was also on the right side, an arrangement I never cared for. Since the cockpit was so narrow and the right stick so close to the fuselage side, I found it didn't make much difference which hand I had on the stick. So, I cross handed and put the throttle in my left and stick in my right. That had the added advantage of keeping my left arm out of Jim's shirt pocket. Takeoff was, shall we say, interesting. As a normal rule, takeoff in a taildragger is interesting because of its tendency to go poking off in directions you don't want to go. Not so the Arrow Sport. It tracks more or less straight ahead (with a few nudges from the rudder), but it tracks and it tracks and it tracks. Those highly tapered wings may be pretty, but they aren't as efficient as you'd like them to be. Combine that with running close to gross weight and a wheezing 100 horses in the nose and you've got an airplane that enjoys taxiing much more than flying. So, it ran on the mains for a while, even though I'd just as soon it went flying. We ate up a prodigious amount of runway to get off and when we did, it took a while longer to get enough speed to climb barely 400 fpm. A rocket it ain't. I was beginning to think I was going to renew my boyhood acquaintance with tall corn before we got off. The controls, unfortunately, don't live up to the airplane's looks. Where the airplane looks graceful and petite, the controls made it handle like a 1952 Peterbilt. They are heavy! However, very little of the aileron forces are due to airloads. Since I never saw much over eighty mph on the clock, airloads couldn't get that high and the system friction in the controls is astronomical. I have no idea what's in the system, but it feels as if the cables are being pulled through granite pulley blocks. When you finally get the controls displaced, the airplane responded well enough, if a little soggy, but it makes you work for your movements. If the system friction was lowered, the airplane would begin to fly like it looks. IT WAS LATE IN THE DAY, NEARLY DARK AND THE Midwest sun was sitting on the horizon like a picture off a calendar. Every thing you looked at was a warm yellow. The yellow played games with the streaks on the windshield where the Kinner was depositing its bodily fluids; forcing me to poke my head out around the windshield to see, whenever we turned into the sun. As I did that, I'd feel the heat of the engine on my face. The heat didn't feel like it was nearly fifty years old. The five-cylinder foot warmer up ahead had been around for nearly fifty years, but seemed to pop and purr the way it did the day it was yanked out of the oven. Although the cockpit was a little on the chummy side, it was in no way overly cramped although I wouldn't recommend it for two blubber butts. Jim is built like Abe Lincoln and I'm FAA standard issue 5 ft 10 in, so we fit just fine. If I was homebuilding, I would think long and hard before I bothered to widen the fuselage, although an inch or so might not be too noticeable from the outside. An inch would be welcome on the inside though. Since the panel is one and three-quarter people wide, it's got plenty of room for anything you should want - from the basic basics like Marshall's to an RNAV unit (wouldn't that freak out the boys at Oshkosh or Blakesburg?). If there was one change I would definitely make, it would be putting the second throttle in the middle of the panel so both pilots could fly with it in their left hands. Yes, I did stall the airplane, but they must not have amounted to much because I don't remember anything about them. Not a thing. Zip. Zilch. At some point in our lollygagging around we noticed that if we stayed up much longer they were going to have to turn on the runway lights so we could land. And there weren't any runway lights. I never had gotten much above pattern altitude, so I nosed her into the pattern and started lining up on downwind. At the time I didn't think much about the fact that Jim and I never had really done much talking about how the airplane flies. We had started to go for a ride and somehow wound up with me playing with the controls. When I saddle-up a new bird, I usually like the owner to talk me to death about how it flies and especially how it lands. Jim and I just never got that far. Anyway, on downwind I figured I'd fly it like any other biplane - a little high on final - so I could slip it down if need be or so I could glide in if it quit. However, the first time I brought the power back, while turning base, it was obvious that a slip was going to be the last thing in my mind. Again, I wasn't thinking too far ahead. As I turned final, I had to grab a handful of horses to keep us on a less than vertical glideslope as the airplane seemed to have the altimeter hooked directly to the throttle. It punched through any minor turbulence like it had a much heavier wing loading, again something of which I should have made a larger mental note. I was fascinated by the gorgeous visibility over the nose and selected a touchdown spot a quarter of the way down the grass runway. As we approached the ground, I gradually brought the nose up and started feeling for the ground. Then I made the first mistake . . . I killed the power. You would have thought the throttle was the executioner's lever on a gallows because it felt like we fell through the trap door. Bam! Just like that, we fell out of the air. I don't know if I had let the airspeed decay or whether the heaviness I had been feeling earlier really was that of a heavily loaded airplane. Marshall later told me he always carries power into the flare and gently brings the power back to lower the airplane onto its gear. Later he told me that. As we were rebounding off the runway, neither of us was in the mood to hold a debate on what I'd done wrong. I guess I've made worse bounces but, at that moment, I was more concerned with getting some power into it and softening the fall out of the other side of the bounce. It turns out Jim was having the same thoughts. Suddenly, I realized I didn't know who was flying the airplane and, evidently, the airplane didn't either, as it wallowed ahead on the runway, Jim couldn't resist joining the fun. So I hollered, "You've got it" and settled back to watch the excitement, which was, fortunately, short-lived and happily concluded. I had broken one of my cardinal rules in not getting a thorough briefing on an airplane and then broke yet another one in not discussing well ahead of time who was going to do what if the flight came unraveled. It wasn't the airplane's fault and Jim had no trouble getting things straightened out -- once there was only one set of hands flying the airplane. But I learned from the experience. It wasn't until later that I found out Jim had just bought the airplane and only had ten or fifteen hours in same, so I don't blame him for jumping into the fray. Jim makes no secret of the fact that all credit for the restoration of his airplane goes to Dr. Roy Cram of Burwell, Nebraska. Cram has rebuilt two Arrow Sports, the first of which now hangs in the Lincoln airline terminal. Jim talked him out of the second one. In this day of hot-wired foambuilts and kites that sound like chainsaws, it's nice to know that there are a few folks who take it upon themselves to preserve the remaining slim connections with our aerial past. Marshall and Doc Cram are such people. They see the Arrow Sport not only as an incredibly cute little bugger but as an artifact of their state's history which they want to preserve. Everybody profits when something like this is saved. It gives us a glimpse of a part of aviation history that many never knew existed.

|