Yes sir, sports fans, there I was, blasting along over the beach, indicating 500 knots. I tweaked back on the stick, the VSI zipped past 6000 fpm and the needle buried itself in the peg. In seconds, seconds mind you, we were rocketing through 10,000 ft, my hand quivering and my mind suitably boggled. I'll never be the same again! Now that I've lost my jet virginity, it's going to be tough stepping back to the groundhog performance of prop-swinging airplanes. I don't know whether to thank the Blue Angels or not for lighting a fuse to a heretofore sealed keg of discontent.

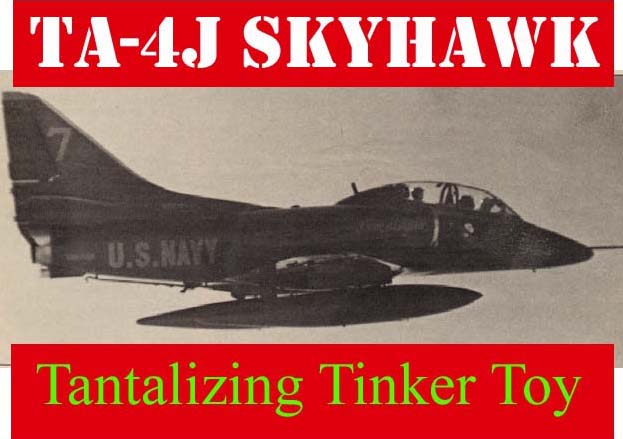

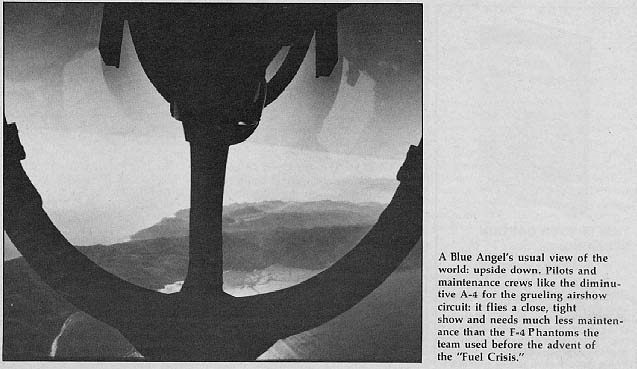

The blowtorch that turned my head inside out was the Angels' TA-41 SkyHawk II, a spidery-legged arrowhead of aluminum and fire that today, 20 years after its first flight, is still the most widely used tactical aircraft in the world. It's a tiny thing, with the sort-of-ugly, pugnacious look that says it's built for business, not looks. When the sheiks started shaking up the world and the supply of JP looked like it might indeed be limited, the U.S. Navy saw it was time to clean up its act. So, the Blue Angels said good-bye to their hulking, bulldoggish F-4 Phantoms and hopped into the nimble little A-4. With a third the weight and a corresponding drop in operating costs, the A-4 seemed like the logical way to do the public relations number and still not sop up all the jet fuel in sight.

It was through the Blues that I got to live

out those fantasies that used to flash on the screen of my mind's

eye. Since I'm color blind, I never had a chance at being a jet

pilot simply because grass looks red and stop lights have funny

colors. So, I had completely given up any idea of flashing through

the skies as the lord of my very own fireball. But, through a

weird combination of timing, people and pure luck I found myself

looking at mach meters and EPR gauges in the back seat of the

Blue Angels' 2-seat TA-4J.

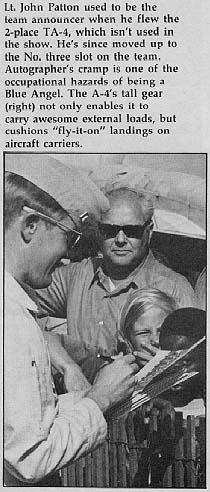

As I walked toward Blue Angel Seven with R.V. King, the crew chief,

and Lt. John Patton, the incredibly boyish-looking pilot, I felt

as if we were short-circuiting what should be an incredibly complex

check-out procedure. Where were the compression chamber check

and the blow-it-out-your-canopy ejection-seat checkout? It was

instead a simple matter of "Oh, hi, Budd! Yeah, let's go

flying."

King strapped me in and introduced me to a lot of goodies which the military takes for granted, but which we civilian types don't even know exist. The parachutes, for instance, have a quick-release feature that separates the chute canopy from the harness so you can put the harness on outside the airplane, and then hook up to the bulky canopy once in the cockpit. The rear ejection seat can be fired automatically from the front seat or by reaching over your head and pulling on a handle. That brings a shield down over your face and pow, you're someplace else, pronto!

The panel does its best to confuse. There are

dozens of round foreign dials that assault the eye and prevent

understanding. I had to ignore the panel as a whole and look at

each dial in turn. "Oh yea, there's the airspeed. And that's

a radar altimeter." Engine gauges such as the percent tachometer

and EPR (Exhaust Pressure Ratio) gauge were familiar only because

I'd read a lot of the right books.

I was still looking at this and that when I caught a movement

out of the corner of my eye. It was King on the ground moving

his hand over his head in a circle, and a subliminal feeling of

spinning turbines was working its way through the airframe and

into my body. Then Lt. Patton lit the wick, and it caught with

a gentle "whoom."

We had taxied to the runway before I could

convince myself that this whole thing was for real. "Blue

Angel Seven," announced the tower. "Cleared for takeoff."

Determined to glom everything I could from this ride, I gently

rested my hands on the stick and throttle to follow Patton through.

Then, without warning, he banged the throttle forward so hard

he literally jerked it out of my hand. If one of my students did

that with a Cherokee we'd spend days picking up the pieces.

Whatever you've heard about a jet's slow acceleration, forget it. For just an instant we sat poised there, surrounded by a muted roar, hardly moving at all. Then, with incredible smoothness the airspeed indicator leaped up to 80 knots, then 120. At 120 the stick came hard back into my lap, which surprised me so much I jumped. I hadn't expected such large stick movements. But as the stick jerked back and the nose bobbed into the air, Patton quickly neutralized it to stabilize the nose attitude and we were dying. No, we weren't just flying, we were flying! As soon as his left hand slapped the gear lever up, the airspeed ripped through 200 knots. At the end of the runway the needle was touching 300 knots.

The pattern for Pensacola

calls for an exit below 500 feet until the beach. (The neighbors

must either love jets or buy ear plugs by the gross.) By the lime

we had hit the beach, about three miles down the pike, the air

speed had stabilized at 500 knots and it was time to go upstairs.

From beach level we pulled hard up into a high arching right turn,

approaching a 90° bank while climbing over 6000 fpm. (It was

probably climbing much faster, but 6000 is the biggest number

on the VSI.)

The pattern for Pensacola

calls for an exit below 500 feet until the beach. (The neighbors

must either love jets or buy ear plugs by the gross.) By the lime

we had hit the beach, about three miles down the pike, the air

speed had stabilized at 500 knots and it was time to go upstairs.

From beach level we pulled hard up into a high arching right turn,

approaching a 90° bank while climbing over 6000 fpm. (It was

probably climbing much faster, but 6000 is the biggest number

on the VSI.)

Right then, as the ground was disappearing, the sky turning the same hard blue you see in astronaut films and the Gulf of Mexico spreading out like a plastic-perfect ocean from a movie set, my mind lost its grip for just a second. It was all too much. Dammit, I told myself, this is just too perfect, too smooth, too everything to be real. At the top of the turn the 90 degree bank turned into a flawless positive-G roll, and my mind was in real trouble. I couldn't cope with it. I wanted to scream out at the world, "Look! Look at what I'm seeing! My God, get up here and look! It's too beautiful to simply write about. It has to be lived!" I gave myself a severe talking-to and gained some control just as the headset whispered the words I'd been dreaming about: "Okay, it's your airplane."

I'm going to have to admit something. All the way down to Pensacola on the airline I had planned to really do a number on Lt. Patton's mind. I figured I'd keep a low profile during the ground briefing. You know, just mention having flown and not delve into what I, at that point, thought was an exciting aviation background. The Plan called for me to be Mr. Cool until he gave the airplane to me and then I was going to astonish him with a lightning-fast kaleidoscope of computer-perfect acrobatic flight. Eight-point rolls with edges so sharp you could shave on them. Loops with effortless, precisely placed rolls on top. Then I'd finish with several on-the-money vertical rolls and level out, waiting for him to stand up in the front pit and applaud.

I can't begin to tell anybody how incredibly stupid I felt when

I placed my (so I thought) well-trained hand upon the stick and

couldn't even hold level flight! Just the pressure of my hand

holding the stick sent the airplane into a three-dimensional gyration

that probably had Lt. Patton in gales of laughter. Control pressures?

There aren't any. None. Zero. Zip. Zilch. And the travel of the

stick could be measured in micro-something-or-others. I'm here

to tell you that no matter what I've flown that was supposed to

be sensitive, nothing, absolutely nothing, holds a candle to this

thing. It makes a Pitts (and I'm not kidding a bit) look like

you need two hands to make it turn.

After I overcame my initial shock, I settled down to make this thing fly. The controls are hydraulically boosted and there's a very slight dead spot in the middle, so the slick kind of floats between four hydraulic contacts until you move it a bit to touch one. Then the airplane leaps to your command. Noting that, I relaxed my grip on the stick and just kept a couple of fingers close to it. After five minutes of gentle turns (it's darned hard to fly them gently in this airplane) and Dutch rolls, I began to get a little feel for where center was.

My first roll wasn't much better than my level flight. As I came back level, I wiggled back and forth trying desperately to find the middle position for the stick. After each roll, I'd do a 180; Sixty degrees or more seemed a normal bank angle. Still, I was being timid with the airplane. I'd gently move the throttle when I thought I needed power and tip-toe into rolls using only Pitts-like roll rates. But, as I warmed to the airplane, Lt. Patton kept urging me to not baby it.

So, little by little, I came to know the A-4. Within an hour the almost impossibly sensitive controls became perfect. The total irresponsibility with which you can treat the airframe and engine leads you deeper and deeper into the airplane's personality. It was fun to finish a maneuver and jerk violently over into a better-than-90° bank and pull hard for a four-g diving turn; all the time watching the airspeed move up to 500 knots indicated (and at 15,000 feet yet!). Then I'd rip back to level flight for an instant before arching up into a blood-sucking loop, holding 4 g's longer than any civilian ship ever will. The rudders came into play only once in a while and the ailerons are so incredibly light and quick that any measurable movement of your hand produces a syrupy smooth aileron roll, or two, if you don't neutralize quick enough.

I tried to time the

roll rate with my watch, but one roll happens so quickly you can't

time it. So, I tried a double roll. Still too fast. Then a triple

and finally we were doing four consecutive full-deflection rolls

at a 30° nose-high attitude before I could get a reasonably

accurate count. What was the roll rate? Only a sedate 400°

per second. To put that in perspective, a Cessna is in the 75-90°-per-second

range and a Pitts, the legendary fast-rolling Pitts, is only 180°.

Four hundred degrees a second is so fast that your eyeballs take

one more lap after the airplane has stopped turning.

I tried to time the

roll rate with my watch, but one roll happens so quickly you can't

time it. So, I tried a double roll. Still too fast. Then a triple

and finally we were doing four consecutive full-deflection rolls

at a 30° nose-high attitude before I could get a reasonably

accurate count. What was the roll rate? Only a sedate 400°

per second. To put that in perspective, a Cessna is in the 75-90°-per-second

range and a Pitts, the legendary fast-rolling Pitts, is only 180°.

Four hundred degrees a second is so fast that your eyeballs take

one more lap after the airplane has stopped turning.

This whole jet-at-altitude routine was surrealistic. There is absolutely no vibration or hint of anything moving at all. It's almost as if the airplane is standing still and the earth and sky rotating around it. The cockpit is pressurized to 21,000 feet, so little noise enters the cockpit, and what does is muffled by the tight-fitting helmet. In flitting around the sky, altitude losses and gains happen so quickly that I found I had to study the altimeter to be sure I read it correctly. One second we'd be bombing along at 18,000 feet; moments later the second altimeter, the radar job, would light up as we screamed down the beach 70 feet above the waves.

Navy pilots fly the airplane onto the ground by a fantastically precise method. On the top left of the panel is a narrow gauge that protrudes right into the pilot's field of vision. In it are three lights; a circle with a v-shaped chevron above and below the circle. It's a heads-up angle of attack display. When the angle is right, the middle circle is lit. When the nose is high, or "slow," the top chevron lights up; when low, or "fast," the bottom one tells him to bring the nose up. The glide slope is determined by the mirror or "meat ball" on the side of the runway. It's a little like a VASI system. When you're in the groove, the orange light appears in the middle of the mirror. If you're sliding low, the meat ball moves down. So, the pilot just mentally connects the throttle to the meat ball. When it goes down, he adds power, and vice versa. Of course, this is all coordinated with the angle of attack display- It's quite like watching the runway numbers and monitoring airspeed at the sametime, but the Navy just has a better, more accurate way of doing it.

While Patton flew the approach I was all hands and eyeballs. I wasn't going to miss a thing. Wham! Into the break, hands flying around the cockpit getting speed brakes, landing gear, flaps, spoilers and everything else in sight. On-speed opposite the runway, the circle in the angle of attack display glowed and we showed about 125 knots on the speed gauge. Arching around in an almost constant turn right down to the ground, he started calling out the meat ball for me, showing how it moved up and down and how you controlled it. Then he called the tower "Blue Seven for a touch and go." Whooee! We aren't done yet!

The second time around I sort of muscled my way onto the controls and then suddenly found myself asking, "Did the airplane move when I did? Or was it vice versa? Who's flying this thing?" No matter, I concentrated on that angle display trying to keep the middle circle lit. Was that me? I doubt it. But, maybe . . . ! In the groove, meat ball centered in the mirror, cross-checking A of A, moving nothing. Then wham! We smoke the tires onto the runway and the tower clears us for another one.

When we finally taxied in, I found that any splinter of cool

I had at the beginning had disappeared in a flourish. My face hurt and I thought

at first it was the g's. Then it hit me-I'd been grinning so hard my cheeks

were overstressed. I must have looked like I was auditioning for a toothpaste

ad. I just couldn't get my lips together.

For lots more pilot reports like this one go to PILOT REPORTS