It's interesting how people line up behind their favorites, whether it's base ball, politicians or airplanes. There a love 'em or leave 'em attitude that clearly separates folks into two distinctly different camps, regardless of the subject. Which is, of course, what makes conversations about such subjects so volatile. But, that's not going to stop us from venturing forth into controversy-land and comparing the Pipers to the Cessnas.

Before we start tossing numbers around and comparing supposedly important nit-noids, let's talk some generalities about what gives the airplanes different personalities and endears them to specific groups while turning off others.

To begin with, Cessna and Piper had, and have, different views of what an airplane should be and how it should fit what they see as their target market. Cessna has always designed an airplane that is a lighter light plane than Piper. It isn't by accident that they do that. They design to the absolute weakest link in the pilot chain, making an airplane that glides, has a low stalling speed and is generally fool proof in every aspect of its personality.

Piper, is on the other end of the design spectrum. As light airplanes go, theirs are always a little more heavily wing loaded, with higher stall and approach speeds. They come down final a solid 15-20 mph faster than their Cessna brethren. Is this bad? No, it's just different and it leads to an obvious handling difference between the two breeds of flying machines.

Because Pipers are more heavily loaded and faster, they aren't as effected by environmental factors as much as the comparable Cessna. They tend to punch through turbulence, rather than riding over it, and are generally easier in a crosswind. The latter is not only a function of their heavier, faster nature, but because the low wing configuration puts the wing closer to the runway and in a lower crosswind gradient than something with a higher wing (wind goes to zero at the runway surface, so the lower the airplane sits, the less crosswind component it feels). Also, the shorter wing generally means slightly quicker roll rate.

Because of the proximity to the ground, Piper has been limited in their ability to design a truly effective flap system: there is isn't room to crank out 40° of slotted, Fowler flaps. However, even if there was, it is doubtful Piper would have designed such a flap system because their designs have always included a modicum of KISS philosophy (keep it simple, stupid).

The net effect of Piper being heavier than Cessna is that they are somewhat easier to handle in adverse conditions on final. In fact, one school of thought is that, as trainers, the lowly Cherokee 140 is a little TOO EASY to fly because it doesn't make you work hard enough.

Bear in mind, we're splitting hairs here, but these are all very real, tangible differences between the aircraft and how they fly.

As far as the high wing, low wing thing goes: it's a matter of taste because the realities balance themselves off, airplane to airplane. You can see up and to the side better in the low wing, but you can't see down. Boarding each is different, but is one really better than the other? Here you're splitting hairs that have already been split a couple of times. It just doesn't make any real difference.

One thing that does make a difference, when buying one or the other aircraft, is that there are many more Skyhawks out there to chose from than there are Cherokees. Part of this is because the Skyhawk/172 got a head start. The 172 hit the airways in 1956 but the PA-28 Cherokee didn't start rolling until 1962. Even then, however, the Skyhawk is the most produced civilian airplane in the world and has always been cranked out in larger numbers. This alone says something about how the market looks at the two airplanes. It has gotten to the point that the generic term "light plane" conjures up an image of a 172 in almost everyone's mind.

Another major difference is under the respective engine cowlings. Cessna started out with the ultra-smooth 0-300A Continental which pumped out 145 horses and didn't go over to the 150 hp 0-320 Lycoming until 1968. However, the 0-320 Lycoming, which has come to be regarded as nearly bullet proof, was Piper's engine of choice going clear back to the mid 1950's in the Tri-Pacer. In the Cherokee line, they messed with various versions of it, rating it at 140, 150 and 160 horsepower, but it was still the same basic engine. It should be noted, however that the extra 10 horses, 150 to 160 hp, is a noticeable and worthwhile difference. Piper offered that engine right from the git-go, in 1962, with the introduction of the Cherokee. This may have been because the final versions of the Tri-Pacer had that engine. Cessna didn't go to the 160 Lycoming until 1977.

An even bigger, actually astounding difference, is going up to the 0-360 180 hp Lycoming, which Piper offered as early as 1963 but Cessna didn't lock on to until last year. In the late 1970's, they did offer the Hawk XP with a 190 hp version of the 210 Continental, but it didn't seem to sell as well as they hoped.

The Cherokee 180 existed for most of its life in a vacant marketing niche which it had all to itself. It fell between the Skyhawk and the Skylane, both in performance and cost and is still one of the most popular, and useful, Pipers ever built.

Trying to do an exact apples to apples comparison with the different aircraft is complicated by the fact that the Cessna Skyhawk was produced for long periods of time with only minor changes to a single basic model. The Cherokee line, however, always included at least three different airplanes, the 140, 150/160 and 180. Then, beginning in 1974, a new, tapered wing was added and the line branched again to include the Warrior, with either 150 or 160 hp and the 180 hp Archer. The older, Hershey Bar wing Cherokee ceased production when the tapered wing versions were introduced.

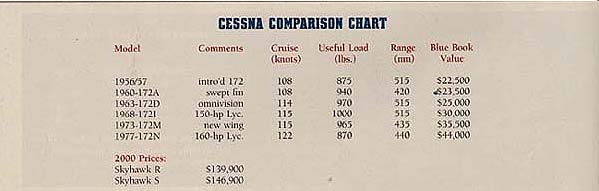

The following chart is an attempt to make some sense of the chronology and performance parameters of the different models at different times. In each Piper case, we're going to do the first and the last of each model. In the Cessna, we'll just do the basic models as major changes occur.

So, what can we compare and what does it mean? If we look at just the Cessnas, and the performance versus the price, it becomes a question as to how much speed is actually worth. Once you get past the first several years, all of them cluster at 114-122 knots, regardless of the engine while payload gradually drifts downward.

Do the same thing with the Cherokees and in every case, they get faster by about ten knots while the payload stays about the same. The exception is the basic 180 which retains its 124 knot cruise through out the 13 year production run and the useful load gradually drifts down from 1170 to 1090 pounds. The Warriors and Archers offer little in the way of more speed or payload over the earlier airplanes.

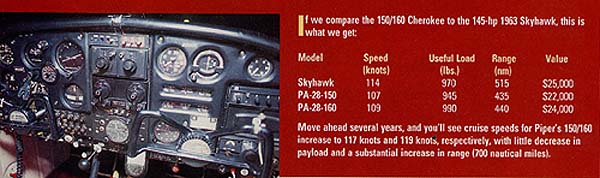

Now what if we look Cessna to Piper? In 1962 Piper introduced the 150 and 160 and a year later Cessna went to the wrap-around rear window giving the Skyhawk the appearance we accept today as being the final form of the airplane, but it still had the 145 hp Continental. It would be five years before they went to 150 hp and 15 years before 160 hp arrived in Wichita. For these reasons, it's difficult to decide what to compare to what.

A closer comparison would be a 1995 Archer versus the new 180 hp Cessna 172SP:

Speed Useful Range Value

Skyhawk SP 124 900 475 $149,000

Archer 125 1134 565 $128,000

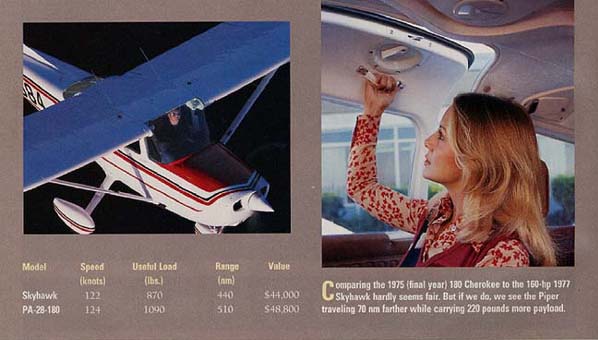

Skyhawk 122 870 440 $44,000

(1977)

The numbers of the 180 horse power 'Hawk can be a little deceiving, if nothing else, because what's not indicated here is a 25% increase in climb. That is at least 200 feet better than the Archer can muster. But, of course, the Archer is carrying 234 pound more pay load.

In general, when you get to the bigger engines, a Piper usually carries a little more but isn't always faster. In the smaller engine ranges, the airplanes are very nearly indistinguishable, with the speed and load advantage shifting from one make to the other in different years.

I hate those kinds of discussions that end with "...and at the end of the day, it really becomes the buyer's taste and preference that makes the difference." Hate those! However, when you get right down to it, that's about what we have here. If you want to carry more weight, the scale edges towards the Pipers. If you have short field problems where approach speed matters, then it's the Cessnas.

The only way to make the right decision is to go out and buy time in any of the aircraft you are considering. There is simply no substitute for trying an airplane on and seeing how it fits. Believe us, you'll know when the fit is right without resorting to number crunching.