Probably 95% of the folks walking through the tent flap had never actually laid eyes on one before. And none could relate it to the name "WACO". To them all WACO's were elegant of line, with two wings and a round motor. Most of the few EAA'ers who found the tent weren't prepared for this WACO and what at first glance appeared to be a blacksmith approach to gliding, structures and aerodynamics.

And very few were prepared for the sheer immensity of its blunt form. The Plexi-glass seemed to waterfall down from the crest of a sizable and very rectilinear olive drab building that dwarfed each EAA'er entering. It was hard to escape the fact that, as gliders go, the WACO CG-4A appears to have all the sleekness and aeronautical cunning of your average cargo container.

But then, that's what the CG-4A was...a cargo delivery container meant to carry the tools of war where today the helicopter would go. In 1944, however, the only alternate vertical on-site delivery system was the parachute and it wasn't reliable. And couldn't carry jeeps or artillary assembled and ready to go and know for a fact where they were going to wind up.

But,

it wasn't just the glider on display in that tent. What was actually

on display was a major chapter of our history and the deeds of

a largely unknown and not-so-small group of aviators.

But,

it wasn't just the glider on display in that tent. What was actually

on display was a major chapter of our history and the deeds of

a largely unknown and not-so-small group of aviators.

Ask yourself how much you actually know about the glider's use in WWII. Make that even easier by asking yourself what you know about the CG-4A and the people who flew it. It was, afterall, America's primary (and just about only) operational combat glider. We should all know something about it, if nothing else because it is so big. And so "distinctive" looking for a glider.

As one of the glider pilots standing around the tent commented, "The Air Force has never owned anything as ugly, or as effecient."

Still, as huge as the airplane was, it still remained one of the, if not the, best kept secret of Oshosh this year. Unless one took a deliberate side trip and waded through the jets and other exotica parked on the west ramp, it was easy to miss the white tent which contained a celebration of silent wings and the warriors who rode them into battle. It had its own on-going movie theater but what made it unfortgettable was that the tent was filled with the original cast, both human and mechanical, of the grainy documentary films being shown.

In

the films they were young and smiling. As they stood around the

wingless fuselage of the Kalamazoo Aviation History Museum's freshly

restored CG-4A at Oshosh and told their tales, they may not have

been quite as young, but they were still smiling. And they were

proud of the chapter of history they had helped write.

In

the films they were young and smiling. As they stood around the

wingless fuselage of the Kalamazoo Aviation History Museum's freshly

restored CG-4A at Oshosh and told their tales, they may not have

been quite as young, but they were still smiling. And they were

proud of the chapter of history they had helped write.

There were actually three stories that need telling in that tent. There is the history of the airplane, then the story of the men who flew them and then there is the much more recent saga of the Kalamazoo Air Zoo's struggle to add a CG-4A to their already impressive collection. Any one of the stories is worthy of a book or a movie We'll have to settle for a few brief words in passing.

First the airplane: America didn't originate the idea of landing troops and equipment by glider. The axiis had used the concept almost from the first day they rumbled across Poland's border. Once again, America was having to play catch-up because the bad guys had a jump on us.

But playing catch-up in wartime usually means having to make-do. It means having to freeze a design or a concept as soon as a workable solution is developed because war doesn't give time to re-do or refine. The time frames make for some wonderfully workable, although sometimes border-line crude, solutions to problems. This is something we're really good at.

No one will ever say John Garand designed a sophisticated, finely crafted machine in the M-1 rifle. But no one will ever argue it was supremely reliable and deadly accurate and its ease of production gave us the only widely-issued automatic rifle of the war. The enemy could laugh at the surface crudity of many of our tools of war, from the jeep to the bazooka and on down.

Eventually they found they had to look deeper to see there can be a subtle sophisitication in what they sometimes dismissed as a typically frontiersman solution to a problem. What they missed was the one thing Americans have always been the world's best at...simplicity. Our solutions may not always be beautiful and are sometimes a little ragged around the edges, but they work. They do the job with a minimum of hassle.

During the war what many of our enemies mistook for a crude approach to design was actually a very American way of figuring out the best way to get the job done with the smallest number of parts and the highest level of produceability.

That very much describes the CG-4A. Out to get the job done. Although the military knew the other side had far surpassed us in the size and effectiveness of their cargo gliders, our planners knew they couldn't wait until the perfect solution came along. They selected the WACO design as the winner of the competition and put put the CG-4 into immediate mass production. LIke so many other aspects of WWII, what we lacked in sophistication we made up for in numbers.

If it can't be produced effectively, what difference does it make how good it may be?

The CG-4A glider is a study in simplicity. In concept, the fuselage is nothing more than a huge tubing box with the nose vaguely blunted and gigantic Hershy bar wings attached. When WACO submitted their proposal there was at least one other airplane that carried more and glided better. But it coudn't be produced as easily. It would take skilled labor. The WACO wouldn't.

The airplane has some beautifully Goldbergian (as in Rube) operational features. For instance, the complete nose section, pilot seats and all, hinges up and out of the way so the cargo can be loaded straight in simply by pulling a couple of pins.

A

side benefit to that concept is it can be unloaded even quicker

and protects the pilots in a really neat way. The gliders were

sized to carry 13 men with combat equipment or a 75 mm howitzer

attached to a jeep, or a jeep pulling a trailer load of ammunition.

A healthy cable runs from the top of the hinged nose section back

down the top of the fuselage, turns through a pulley and is then

attached to the back of the jeep or howitzer. Then, as soon as

the glider touches down a latch is tripped on the nose section

so, if the load breaks free and tries to exit the front of the

glider, its movement forward will yank the nose and the pilots

up out of the way. In effect the airplane vomits out its load

without squashing the pilots.

A

side benefit to that concept is it can be unloaded even quicker

and protects the pilots in a really neat way. The gliders were

sized to carry 13 men with combat equipment or a 75 mm howitzer

attached to a jeep, or a jeep pulling a trailer load of ammunition.

A healthy cable runs from the top of the hinged nose section back

down the top of the fuselage, turns through a pulley and is then

attached to the back of the jeep or howitzer. Then, as soon as

the glider touches down a latch is tripped on the nose section

so, if the load breaks free and tries to exit the front of the

glider, its movement forward will yank the nose and the pilots

up out of the way. In effect the airplane vomits out its load

without squashing the pilots.

If the landing is normal, the jeep just drives out the front and pulls the nose up as it does.

The wings span a gigantic 83' 8" and are made entirely of wood. The spars are boxes with laminated spar caps and plywood faces. They are joined 23' feet out from the fuselage with the inner sections being braced for torsion by a pair of healthy streamlined struts. The outter panels carry torsion by being completely skinned in plywood.

The struts, incidentally, aren't streamlined tubing but round tubes with aluminum ribs front and back. Then they were fabric covered.

Originally, the landing gear was to be of the drop-off variety and in combat the airplane was supposed to land on the spring loaded skids that run down both sides of the flat belly. In operation, however, they found the airplane could make better, more controlled landings if the rudimentary gear was left in place. The wheels and brakes are basically identical with a T-6 with larger tires. The brakes and the spoilers are hydraulic with the controls being of the Armstrong variety.

In

its most produced form, the airplane's empty wieght was 3,340

pounds with the gross weight officially listed as "...7,500

lbs and up". If a Gooney Bird could get it off the

ground before the pilot aborted because he was out of runway,

they flew it. The towing speed was 120 mph and the normal stall

was 50 mph, which of course, didn't mean anything if it was grossly

overloaded.

In

its most produced form, the airplane's empty wieght was 3,340

pounds with the gross weight officially listed as "...7,500

lbs and up". If a Gooney Bird could get it off the

ground before the pilot aborted because he was out of runway,

they flew it. The towing speed was 120 mph and the normal stall

was 50 mph, which of course, didn't mean anything if it was grossly

overloaded.

When the contracts were let for production they were made directly between the government and the contractors. Oddly enough, even though it was a WACO design, they actuallyh only built about 1100 of the nearly 14,000 finally produced. A total of 16 manufacturers were awarded contracts with Ford producing nearly a third (4,190) of the total. The average price was $25,000 but they ranged from a high of $52,000 to Ford's $15,000.

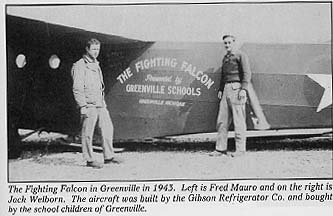

The contractors included the expected names like Cessna (750) and Pratt, Read (925) to the unexpected like Gibson Refridgerator (1078) and Ward Furniture Mfg (7).

The simplicity of the airframe was ready made for construction by companies with no previous manufacuring experience. All they needed was the ability to cut and weld tubing and work wood. Big pieces of wood. In actuality, few manufacturers did all the work in house. The most common approach was for the prime contractor to do the fuselages and steel work with all the wood work being farmed out to those with expertise in wood, notably furniture manufactures. The parts would flow in from the various subcontractors and were assembled at the main plant. Incidentally, one of the major sub-cractors was Baldwin Piano.

Woodworking capability is one reason so many of the gliders were built in Michigan where they were suported by the already existing furniture industry. Between Ford's plant at Kinsford and Gibson's plant at Greenvile, they cranked out 5,270 of the machines.

When the war came to an end the fate of the CG-4A was obvious: There wasn't a single possible civilian use for the airplane so it was surplused as quickly as possible, where ever possible. The airplane's themselves were practically useless, since they didn't even have enough instruments worth salvaging.

What

did make them valuable was the military method of packing them

for shipment. The glider broke down for packing in five gigantic

crates. In typical military fashion, the crates weren't just boxes

but used the highest grade pine and fir available. The crates

used so much lumber it was said they could be used to built a

small house. And that's what made them worth the $50-$150 bidders

paid for the complete gliders.

What

did make them valuable was the military method of packing them

for shipment. The glider broke down for packing in five gigantic

crates. In typical military fashion, the crates weren't just boxes

but used the highest grade pine and fir available. The crates

used so much lumber it was said they could be used to built a

small house. And that's what made them worth the $50-$150 bidders

paid for the complete gliders.

They would drag the crates out to the farm, push the glidger junk out into the trees (after burning the wings) and use the boxes for the lumber.

The surplus sales around the major manufacturing sites sent glider components out into the surrounding country side in wholesale lots. The production lines were stopped mid-step and what ever was laying around was sold. Partially completed components of all types were carried out of those sales in truckload lots. There is, for instance, a hangar at Sparta, Michigan that uses surplus CG-4A spars for beams.

Compounding the proliferation of glider parts going into barns and outbuildings was the diversified nature of the subcontractors. Many were located in small towns, so the bits and pieces they were manufadturing probably never made it more than a couple dozen miles away from the auction site. Most of the completed small parts weren't even worth carting off, since not many needed giant wing ribs or widgets that could only be used if you were building a CG-4A in your basement work shop. In all but a few cases, the stuff that couldn't be sold was simply burned.

Long before the Korean war started the CG-4A was almost entirely extinct or in the process of sinking into the soil in many forests and fields around the country. It was barely a memory except to those to flew it.

To those who sat at the WACO's controls stretched out on the end of a 300 foot tow rope watching tracer chase them through the still dark skies of a European dawn the memories never faded.

Standing

around the huge WACO at Oshkosh the memories were recalled used

to paint graphic images of a portion of the war which few understand.

The war in the air is usually imaged as Mustangs and Flying Forts

and this has pushed the glider pilots' contributions off to the

edges of our collective memory.

Standing

around the huge WACO at Oshkosh the memories were recalled used

to paint graphic images of a portion of the war which few understand.

The war in the air is usually imaged as Mustangs and Flying Forts

and this has pushed the glider pilots' contributions off to the

edges of our collective memory.

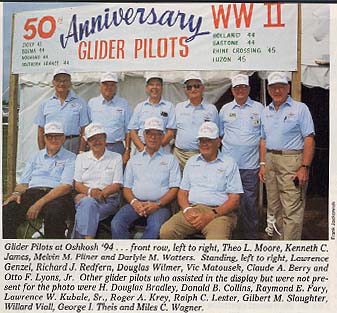

At Oshkosh we were able to spend some time speaking with three

CG-4A pilots who had all flown the airplane in combat. Darryl

Waters, from Hazlet, Michigan was one of the first 22 CG-4A instructors,

went on to fly a load behind the lines on D-Day (in a British

Horsa, which he hated). He spent nine months in Stalag Luft 1

after a Colonel towing him cut him loose when his C-47 came under

fire. Darryle was the old man of the group at the at at 24 years

old.

Otto Lyon's, Germantown, Tennessee, still lives at the same address he did when he inlisted at 19 years old. He was operational in CG-4As by the time he was 20 years old and holds many fond memories of the old glider.

"It handles great," he remembered with a lot of enthurisasm showing. "It would trim up beautifully and practically fly itself on tow. We used to kid that that the airplane would land itself and several times they did, after a pilot tailed out. I watched one bail out after gittin into a flat spin and the glider set down with just a little bit of damage.

"We

could actually termal the thing in Texas, and with a normal load

it had a glide ratio around 12:1."

"We

could actually termal the thing in Texas, and with a normal load

it had a glide ratio around 12:1."

He looked around and laughed at the rest of the guys, knowing they'd probably done the same thing and said, "Why, I even looped the big thing!"

Mel Pline, from Pegosa Springs, Colorado, volunteered for the Army Air Force because he already had three summer training camps in artillary and definitely didn't want to be drafted into field artillary. He wound up flying gliders because he wanted out of the motor pool in the worse sort of way but the waiting list for pilot training was to long. The cadet office had just received a TWX looking for glider pilots and he coudn't put his name on the dotted line fast enough. He signed up on Tuesday and was on his way to Pittsburgh Kansas on Thursday.

LIke the other three, Mel originally went to flight training in what they referred to as "Dead stick" school. They'd be training in one of the three light L-birds (-2,-3,-4) and as soon as they were able to fly the airplane in the normal manner they started killing the engine for deadstick landings.

Then they transitioned into their first gliders, some of which were Schwietzers or Laister-Kauffman's but others were nothing more than Piper Cubs, engine removed, wieght added and seating rearranged. Many of the Cubs flying today are old gliders .

Glider pilots were, for the most part, Flight Officers and were assigned to Transport Command. As such, even while they were operational, they existed in a sort of non-category that dogged them for many decades after the war.

The infantry thought they were Airborne, the Airborne thought they were Airforce and the Air Force thought they were or Airborne.

Darryl Waters said, "When I was a POW, the German's treated us as Air Force and put is in the Air Force POW camps, when out own forces didn't know for sure what we were. In fact, glider pilots didn't get the Orange Lanyard for the Holland operation until 35 years after the war and that took going right to the Queen. Although a Colonel headed it off before the Queen got involved. Everyone thought they got the lanyard as part of the Airborne awards.

"Nobody gave us any respect because theye didn't know what we were. After D-Day, when we started brining supplies in to the airborne troops behind the lines that started changed. We'd bring in a 75 mm howitzer on a jeep with the ammo in another glider. In two ships we changed them from a light infantry unit to a medium and they could fight the tanks and artillary. Then they knew what we did and who we were."

On their first flights in any invasion their flights would be carrying infantry units. A lot of men who were traveling light and expected to carve out an area they could hold until they began to get supplies and replacements. There would be as many as 1000 gliders at a time in a train on the initial invasion. From that point on, until they could safely be reached by truck convoys, gliders shuttled in ammunition, medical supplies, artillary and jeeps and what ever else they needed.

Some of the missions didn't come off, at least one of which didn't upset Darryl Waters, "If Patton hadn't taken Paris when he did, I was going in with a full load, 4,500 pounds of C-compound explosive. We had the stuff stacked to the roof He probably saved my life."

Mel Penner

remembers, "I was really overloaded, had aseven clover leaf

clusters of 81mm ammo a water cooled .50 cliber machine gun and

15 men. I could barely get off the ground. As we were on downwind

at 400 feet, we started seeing the tracer coming. Normally you'd

be bouncing around, but we were so heavy we were smooth. All we

could do is watch it coming.

Mel Penner

remembers, "I was really overloaded, had aseven clover leaf

clusters of 81mm ammo a water cooled .50 cliber machine gun and

15 men. I could barely get off the ground. As we were on downwind

at 400 feet, we started seeing the tracer coming. Normally you'd

be bouncing around, but we were so heavy we were smooth. All we

could do is watch it coming.

"Most of it missed, but I couldn't glide under 80 mph when 60-65 was normal, so I had the guy in the right seat pick up his feet as I used a fence to stop us."

But landing, as hard as it was, wasn't always the end of the adventure. If the glider landed behind the lines, the pilot became part of what ever he was carrying. If it was troops, he was in the infantryh, if it was a howitzer, he was artillery. Standing orders, however, if road transport was available was to immediately make it back toEngland to fly another glider back. That meant finding headquarters and a ride hope.

After one mission, Penner and a few other glider pilots were standing around waiting for a ride home when a Colonel pointed at them and said, "...they don't look like they are doing anything, use them for replacements..." Not knowing they were glider pilots, the Colonel had unknowingly manned his entire forward position with nothing but officers, reportedly the only time that happened during the war.

The nature of glider warfare was that although the glider may have been part of a flight, it was loaded differently and landed in slightly different, sometimes wildly different, situations. The result is each glider pilot has his own variation of stories to tell. Their experiences are as different as their personalties.

But they are united by one factor: the WACO CG-4A. They had all ridden the same mount into battle and that was a shared experience.

The tragedy of Oshkosh is that everyone wasn't able to sit and talk with some of the pilots and gain an insight into a part of history few of us know anything about. There are a number of good books about the glider war, but nothing beats hearing it from those where were there.

Unfortunately, we once again run into an inherent problem with the written word, we don't have enough space. Just our brief time with Waters, Penner and Lyons gave us enough personal history to write a small book.

All we can say is, we wish you all could have been there.

All airplane restoration projects have an element of the treasure hunt in them. Few aeronautical treasure hunts are as pronounced as that upon which the Kalamazoo Aviation History Museum embarked when they decided to restore a CG-4A.

"Actually, " says Gerald Pahl, the museum's director of education, "We didn't plan on restoring it, but then we didn't expect Darryl Water's enthusiasm and gentle pushing either."

Darryl Waters is, according to every one at the Air Zoo, the spark that not only got the glider project going but also fanned the flame into the full blown project it became.

The project began when Waters began coming into the museum in the late 1980s contributing photos and artifacts to their glider display. Then he planted the first serious seed.

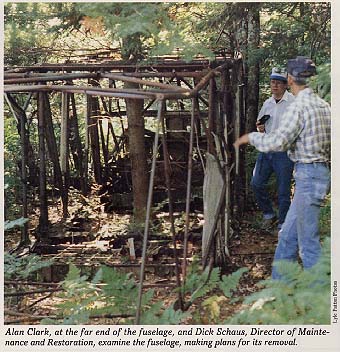

Pahl says, "He came in and said he had located a CG-4A fuselage in the woods up by Ironmountain, Michigan where it had been used as a fishing or hunting shed."

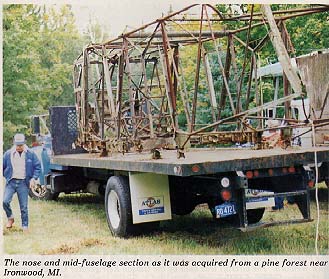

The Air Zoo crew traveled into the woods finding a bare steel framework of the main fuselage section including the nose. It was rusty and bent, and a six inch pine tree was growing through it, but it was there's if they wanted it.

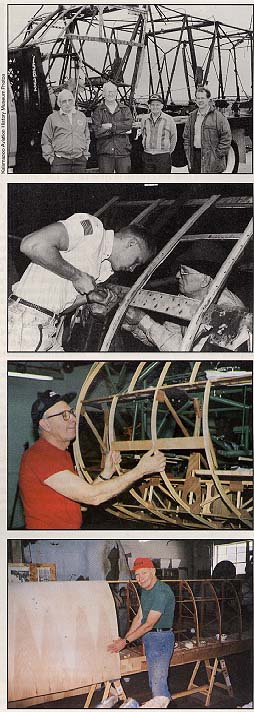

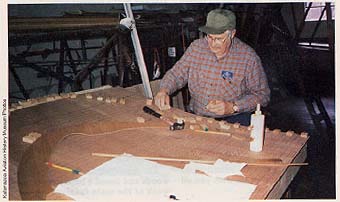

The job of cleaning up the fuselage fell to Allan Clark, one of the museum's technicians who was made project supervisor on the glider.

Clark says, "Originally we were going to just clean up the tubing and have it sitting there as part of the display. But Darryl kept coming in saying he had found this and that and before long, we had a full restoration project going. We hadn't really intended it to go to this extent, but we're glad it did."

Finding parts for something as basically fragile as a glider that 50 years earlier had been immediately determined to be junk wasn't as easy as it sounded. But, somehow things just started happening.

Between Water's enthusiasm and the Museum's network of friends leads started coming in for various parts. Sometimes it was for a single piecs, such as a control wheel. Amazingly, several significant caches of material surfaced.

"We started concentrating on the areas where there had been manufacturing plants or deposal depots and we track down leads in those areas. We made one trip back to the Poconos in Pennsylvania and came up with several rusted hulks in the woods, as well as some smaller parts that were usable." recalls Clark.

One of several major windfalls came in the form of a barn full of "stuff" in upstate New York. According to Clark, the owner had been picking up unusual airplane junk and parts since just after the war. He wasn't a collector as such, but he couldn't leave an airplane sit abandoned so his barn became an orphange for abandoned airplanes. Most important, he had a treasure trove of major CG-4A parts including good tail surfaces, landing gear, and a complete and ready to use floor assembly.

Clark says, "It would have taken us a long, long time to make that floor. It was a really light egg crate type of construction that could hold a Jeep, but weighed very little. The gentleman had kept the stuff inside, so it was ready to use almost as is."

Part of the barn had caved in on the tail section and the huge wings had long since sunk into the ground during outdoor storage, but they still had plenty of exciting stuff in the truck for the trip home.

Although they had a set of blue prints for the wings from the Smithsonian, building up the wings in their entirety would be an enormous job, so they kept looking for parts.

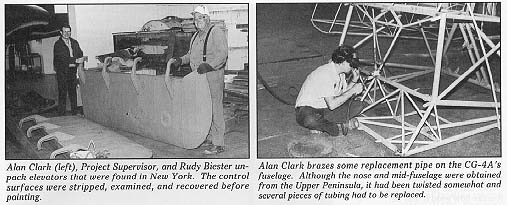

Outter wing spars came from a barn in northern Michigan that had held quite a number of sets, but shortly after the Museum got theirs, the barn burned. The inner panel spars came from not far away in Kent City, Michigan.

Probably the most unusual cache of parts was found in a cave, that's right, a cave in Colorado where one of the sub-contractors had been located. Apparently when they couldn't sell a huge conglomeration of miscellaneous parts, including lots of wing ribs. They couldn't bring themselves to burn them, as so many others had. Their solution was to simply push the parts back into a cave where the relatively dry conditions saved them until the Kalamazoo crowd arrived.

"Some of the parts were water damaged but we still got a truck load of ribs and small parts. Some of the ribs we put right into the wings without doing anything more than putting finish on them," says Clark.

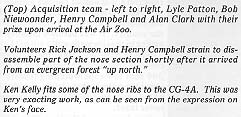

As would be expected, the wings are a monster project and just now nearing completion. It took an amazing total of 60 sheets of aircaft plywood to skin the wings, 1/16" for the outter panels and 3/32" for the inner.

Although the fuselage sections they acquired were fairly complete they were badly rusted and bent. One section, for instance, had been used as a cattle feeder, with hay piled inside for the cattle to eat through the openings. The museum replaced the bad tubing with 4130 and it would have been interesting to hear the comments at the order desk at Wicks Aircraft Supply when the order came in. They must have wondered what Clark and his guys were working on because some of the tubing is over 2 inches in diameter with thin walls.

When the glider was ready for paint, the paint scheme was already fixed in everyone's mind. It had to be The Fighting Falcon , a CG-4A built by Gibson Refridgerator in Greenvile and sponsored by the Greenvile school kids.

Besides the obvious local tie-in with the Kalamazoo based museum, there was another, even larger historical reason to paint their glider in those colors. The Fighting Falcon had been the very first glider to land during D-Day.

Of special interest to EAA'ers, the pilot of that glider was none other than the legenday Mike Murphy, then wearing the silver oak leafs of a Lt. Colonel. To those who don't recognize the name, Murphy was co-founder of the Aerobatic Club of America and a legend in aerobatic and airshow circles before the war. In fact he retired the Freddy Lund aerobatic trophy after winning it three times in a row. He survived the war to become a prominent leader in corporate aviation.

Like we said, the CG-4A at Oshosh was three major stories in one, the glider, the people and the restoration. We haven't done any of them justice. It would have been impossible. Hopefully, we've whetted a few appetites and you'll pick up some books or track down one of the few surviving CG-4As and take a peek at a part of history you may have been missing.

Books for Reference:

The Glider War, James E. Mrazek, St. Martins Press

Silent Wings, Gerald M Devlin, St. Martin's Press

The Glider Gang ?