It's interesting to see what's been happening to the tailwheel of late. For one thing, what had been an anachronistic contrivance designed primarily to prevent an airplane from grinding a bare spot on its posterior, is now being re-valuated in terms of its teaching value. What can the tailwheel teach a student that a nosewheel can't, if anything?

As someone who has been instructing in tailwheels almost exclusively for 35 years, you'd expect that anything I'd say from this point on would be anything but unbiased. But you're wrong. I'm not going to say that everyone should learn on a tailwheel or that you can't learn to fly as well in a nosedragger. I'm not going to say that because I don't believe that. If a person is taught correctly in a C-152, he or she is going to be nearly as good as someone taught in a Cub. Yes, there will be certain differences in that the 152 driver won't be accustom to being blind on landing, but in today's world, is that really necessary?

Now go back to where I said, "...if a person is taught correctly in a C-152..." Now, underline the word "correctly and let's define the term.

"Correctly" when interjected into the tailwheel Vs nosewheel controversy means that the student will be taught to coordinate with the rudder at all times and he or she totally understands adverse yaw. It means that when landing, the airplane is put gently on the main gear, nosewheel clear of the runway and it rolls out that way. A crosswind landing will be with zero drift, on one main gear. The takeoffs will include gently lifting the nose wheel clear, then letting the airplane run on the mains until it flies itself off. If that's the way you were taught and that's the way you still fly, then the only thing the tailwheel is going to give you is quick feet and an appreciation for being able to see over the nose.

Do all students and/or pilots fly that way? Not by a long shot. Not by a very long shot. Why don't they? Because an airplane like a C-152 doesn't require that kind of aviating to be a satisfied, if not truly happy, camper. Its adverse yaw is minimal so the instructor has to work hard to get the student to use their feet in the air because the need for coordination is so subtle. On landing, it's not critical the airplane be straight on touch down so crosswinds are no sweat. Just get it down and the geometry of the gear will sort it out. Takeoffs can be anything you want them to be as long as you have the speed. Just drop the hammer and go.

Finesse, coordination and accuracy have to be forced upon the nosewheel student by a dedicated instructor because most nosewheel airplanes just don't require those qualities to be flown safely. In a nosewheel airplane, the instructor is the single most important ingredient in teaching the student to fly properly because the airplane has made it easy to simply get up and down.

And then there's the tailwheel airplane, the lowly Cub/Champ/Citabria/etc.. Here the instructor is also important, but in the tailwheel airplane he doesn't have to work as hard to teach the basics because the student quickly learns the airplane simply won't go where he wants it to unless he or she masters things like coordination and attitude control. The very basic skills on which all of aviation is built, coordination, speed control, attitude and directional control are absolutely necessary to keep the airplane from becoming a crumpled ball of fabric and tubing on the side of the runway. Getting it up and getting it down isn't really as hard as the horror stories about tailwheels make it sound, but to do it consistently means you've mastered the basic skills of aviation. How many pilots can actually say that? Not very many.

There is the mistaken idea that learning to keep a taildragger straight on landing is the primary benefit in learning to fly a tailwheel airplane. That's not only wrong, but is miles from the truth. Improved directional control is only a tiny, tiny portion of what a taildragger will teach you.

Here's an interesting fact: back when we were working Champs right along side Cherokees, it took about eight hours to safely solo most students in either airplane. Today, to transition a medium-time pilot from nosewheel to tailwheel often takes almost the same number of hours because he has to learn the basics all over again.

Let's look first at the tailwheel airplane in the air, where it doesn't make any difference which end the little wheel is on. If the airplane has a tailwheel, regardless of when it was built (excluding birds like C-180s, 185s, etc.), will have vintage handling. It will have much more adverse yaw than a modern airplane because adverse yaw has been engineered out of modern designs. Push the stick sideways on any tailwheel bird and the nose very neatly moves the other direction unless the rudder is being used. It doesn't move a little. It moves a lot and the student quickly tires of sliding around in his seat and gets his feet into the game for self survival. Therefore, long before the tailwheel comes into play on the ground, the pilot is learning to coordinate simply because he has to.

Hopefully, while in the air, the instructor will point out the way the pilot's butt is telling him exactly what the airplane is doing. The adverse yaw is strong enough that side pressures on the pilot's rear end are noticeable and provide valuable input for proper coordination.

Then there's the landing. Actually, the basics of a proper landing are the same for any airplane, tailwheel or otherwise: a). It should be landed as slowly as practical, b) the nose and the tail should be in line with the direction of travel and c) it shouldn't be drifting sideways. That's all there is to it. The big difference between nosewheel and tailwheel, however, is that on a nosewheel airplane any, or all, of those factors can be screwed up and the airplane will eventually wind up going straight. The landing will be successful, if not pretty. On a tailwheel machine, however, let any one of these factors get out of whack and the landing is going to be an adventure. Count on it!

The geometry of a tailwheel airplane is such that the center of gravity is behind the pivot point of the two main wheels. On a nose gear machine it is in front of the mains, like on a child's tricycle. If the CG is kept right on the line of travel, either airplane will roll straight (more or less). However, if the tail is sideways or the airplane is drifting, the CG is no longer in line with the line of travel and inertia makes the CG want to continue going in a straight line. On a nosedragger, that swings the nose back in line. On a taildragger, the inertial of the CG tries to bring the tail around so that the CG will assume the most stable position which would be in front of the main gear. In other words, a taildragger's most stable position is going straight backwards. This is not necessarily the proper way to end a landing.

It only takes a few trips around the pattern before any student or pilot figures out that his life is a trillion percent easier if he or she plants it on the runway at minimum speed, with all three gear touching (wheel landings are another story), with the tail directly behind the nose and with no drift. If that's done, practically all tailwheel airplanes will roll straight except for gently trying to weathervane into the wind. If it's put on crooked or drifting, it'll start swerving the instant it touches. Like we said, the airplane, not the instructor, tells you it's a good idea to do it right.

What happens almost immediately is that the student/pilot starts to notice little things he never noticed before. For one thing, he'll start seeing what the nose is actually doing just prior to touch down. Tiny little drift angles he never saw in his Cessna/Piper/Beech now assume gargantuan proportions. After touchdown, for the first few hours of practice, the nose will have to move a fair amount sideways before he sees it and corrects. After just a little practice, he'll catch the nose movement the instant it starts and, in so doing, again make his life much easier. In other words, his visual acuity gets much better. He's seeing more of what's happening in the windshield.

Since the severity of turns and swerves on the runway are a function of the speed of the aircraft squared, just a little extra speed on touchdown results in greatly aggravated ground handling. So, the student learns quickly, if he holds it off until it's done flying, he doesn't have to work so hard to keep it straight. He also learns to appreciate a good wind down the runway.

Most, but not all, taildraggers cover the runway with the nose at the moment of touchdown so the pilot has to get his visual cues from the side of the runway. This makes him more aware not only of what's happening somewhere other than on the centerline, but makes it easier to see the drifting, assuming he isn't staring at just one side.

Does the taildragger produce a better pilot than a nosewheel airplane, all other things being equal? No, not really, but it is seldom that all other things are equal. It takes enormous effort for a nosewheel instructor to produce a student as good as any which come out of tailwheels. It can be done, but usually isn't.

If a pilot gets comfortable with the tailwheel, he will have raised virtually every part of his flying skills several notches without even realizing it. Then, when he gets into a nosewheel airplane, he'll be surprised at how much better he is because he is aware of so much more of what is going on around him.

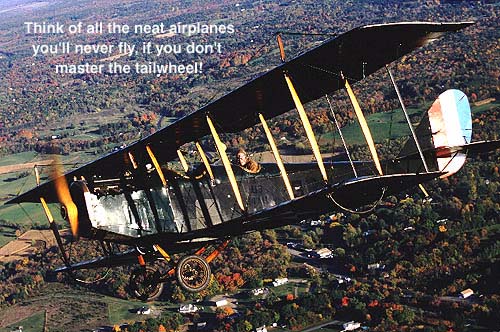

Oh, yeah, there is one other advantage to being able to fly taildraggers: many of the most interesting airplanes have a tailwheel and who wants to be automatically excluded from flying so many neat airplanes just because the little wheel is on the other end.

Flying a taildragger isn't hard. It's just different. And it'll make you a better pilot in spite of yourself.