The other day we were sitting at the end of the runway and a C-172 came around the corner on short final. It was unusual to see a Skyhawk flying such a short approach so I watched it. Then, as the airplane came closer, the pilot eased it into a gentle slip, bleeding off just a little excess altitude before painting it onto the numbers. I was impressed. So smooth, so nice, so accurate. I keyed the mike and said, "Nice job 34 Juliet." And it was. You seldom see the slip used so appropriately these days.

The old fashioned forward slip is one of those maneuvers that on one hand would appear to be redundant to modern flap systems. At the same time, it's one of those basic maneuvers that if understood and practiced gives the pilot yet another tool enabling him to put the airplane exactly where he wants it on approach.

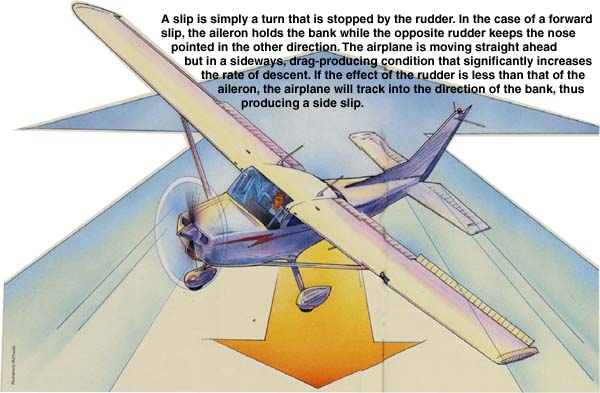

Unless we're talking about the so-called side slip in which a slipping motion to the side is canceled out by the crosswind so the airplane tracks straight, there's really only one reason to slip an airplane; to make it come down faster. That's the short version.

The long version is that because the slip can be put in and taken out at will, the amount of increased descent the slip adds to the already established power-off rate can be varied from zero to the maximum that airplane is capable of generating. The slip can be viewed exactly the same as spoilers on a glider. Spoilers can be put all the way out or left in and varied in such a way that the glide slope can be subtly modified to make it come out exactly where the pilot wants. The slip can be controlled the same way.

The ability to modify the rate of descent from a little to a lot is something many pilots don't understand or take advantage of. They often think you're either slipping, or you're not. In or out. The reality is that, because it can be put in or taken out at any rate and in any degree, it can be used as that extra little touch to change the glideslope.

First a word about how some airplanes do, or do not, slip. First, check the POH to make sure there isn't a prohibition against slipping. Some Cessnas, for instance, carry an admonition in their POH that slips "...are not recommended." They aren't prohibited, per se, they just aren't recommended. Presumably, they aren't recommended because in a full flap configuration the air going across the tail is highly disturbed and the nose tends to bob up and down

Other airplanes simply don't slip well. Usually, it's because they run out of rudder or aileron and can't maintain a steep enough angle to significantly increase drag. Sometimes there's just some strange combination of aerodynamics that will let an airplane fly sideways, but even in that condition, it doesn't want to come down any faster. Every airplane is different and it's a good idea to try it up high first, rather than on final. It's an even better idea to practice it with an instructor who is quite familiar with that particular airplane.

When setting an airplane up to slip, make sure you're at the recommended glide speed because some airplanes get really weird when you attempt to slip them at higher speeds. They don't normally do anything dangerous, but you find yourself fighting them to maintain a nose attitude and to hold the speed stable. Most will be quite stable in the slip when at the right speed. The tendency pilots have of pushing the nose down during the slip and gaining too much speed is one reason people don't like to use slips because some airplanes get down right ornery in that situation.

A word of caution: Be very aware of what the nose is doing during the slip and cross check the speed periodically to make certain you haven't let the nose start to drift up. An airplane that is being cross controlled is really dirty and, if the nose is allowed to come up, it will burn off speed rapidly, which puts you in a very dangerous situation. Check the speed more often than usual and stay right on top of the nose attitude.

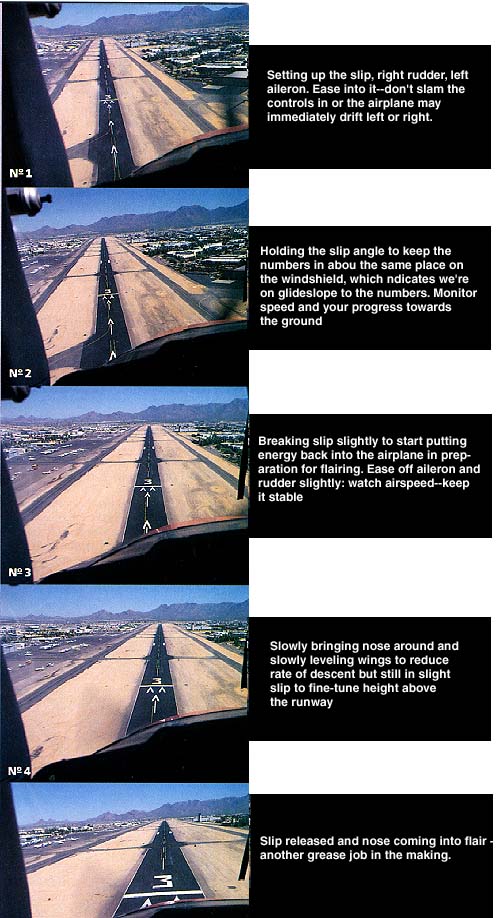

So, for those who haven't slipped much, the first question is probably, "...how do you slip an airplane?" First, what you DO NOT do is simply ram aileron in one direction and rudder in the other. There's more finesse attached to it than that. Enter it by leading with the aileron; put some aileron in and use as much opposite rudder as is necessary to keep the airplane from turning. Then, ease in more aileron and rudder, as needed to make the airplane come down at the rate you want. While doing this, you're holding the nose at approximately the same attitude it had when you established the glide on final and checking speed to make sure it's right.

This is where the optical illusion of the runway numbers moving up and down the windshield really helps. If you're trying to hit the numbers and they are moving towards you (down the windshield), you're going to go over them. If they are moving away (up the windshield), you're going to land short. So, the name of this game is to use as much slip as is necessary to keep the numbers from moving. Also, don't commit to a slip until the numbers are obviously moving towards you. If they aren't moving towards you, you are already on glideslope to the numbers and may be just about to go below it even without the slip. So, make sure you're high, as indicated by the movement of the numbers.

Once in the slip, remember that it's not necessary, nor is it good technique, to simply slip towards the runway and suddenly straighten it out when you think you're at about the right height. For one thing, you might not guess right on the height and the airplane may, or may not, stop coming down immediately. Because the slip can be removed gradually, rather than all at once, it can be used to gently massage that last 50 feet before touchdown. To do that, we're going to treat the slip exactly the same way we'd treat a flair during landing.

Normally, if we weren't slipping, we'd break the glide a little high then gradually ease into a level position ten or so feet above the ground. We're going to come out of the slip, the same way. We're going to start to recover a little high, then, knowing we want to be wings-level at a specific altitude, say five feet, we're going to gradually bring it out of the slip, slowly controlling the rate at which we bring it out, but we don't go completely wings level until we're at exactly the height we want to be.

By bringing it out gradually, rather than all at once, we give ourselves several little control mechanisms that are very handy. For one thing, if we see we're going to be high, we can just come out at a slower rate and let it settle down a little further. If we see we're going to be low, we can come out a little faster.

Another advantage to the gradual type of recovery is that we're putting energy back in the airplane so that in case we're sucked down by some turbulence, or it's hot, the airplane will have regained enough energy to flair. Also, while coming out slowly, we can move the airplane left or right, as well as changing the vertical component. The gradual recovery also lets you more easily see the effect of crosswinds. If you just snap it out level, the crosswind hits you all at one time requiring some fairly quick corrections.

Once you're gotten used to the subtleties of the slip, you'll be surprised how you can use it to fine tune the very end of glide slope. Just as the guy I complimented on final, gently wiped off just a few feet, nor more than five, on short final so he'd hit the numbers, you can use it anywhere in the approach to get rid of unwanted altitude. All you have to be is be smooth and aware of your airspeed and you'll find the slip to be one of the most satisfying and useful maneuvers in the pilot's bag of tricks.