Consider the fixed-gear, four-seat general aviation airplane: How many are actually four-seaters? Yes, they have the seats, but what happens when you fill them? Do you leave more gas on the ground then in the tanks? And what about baggage? Can you and your passengers carry more than a change of underwear and does that has to be stuffed in your pockets?

Many four-place aircraft were actually designed to be "occasional"

four-seaters. Meaning, most of the time all four seats aren't

utilized so the airplane is always flying far enough below it's

gross weight that its performance doesn't suffer very much. However,

regardless of the manufacturer, most of the lower-powered four-place

airplanes, simply give up too much performance at gross weight

to be considered truly usable airplanes in all parts of the country.

Also, a sizable number of the more popular airplanes can't carry

four passengers without off-loading fuel (see the sidebar). Sometimes

a lot of fuel has to be left behind.

There are two notable exceptions to the "four-place

airplanes aren't really four place" rule with another one

or two aircraft that rate honorable mentions. The stand out designs

that really perform as four-place machines should come as no surprise

because that's what has made them so popular; the Cessna 182 and

the Piper Cherokee 235/Dakota 236 line.

Before we get into the heavy weights, lets mention some of the

smaller airplanes that stand out from the pack in terms of four-place

utility.

The Piper

PA-28-180 is a surprising airplane in terms of what it offers

for its cost. If you can believe book figures, you can load all

four seats with 170 pound, FAA-size people, stuff all you can

get into its 50 gallon tanks and still carry 175 pounds of baggage

or cargo. Its sister airplanes, the Archer/Challenger give up

some weight-carrying ability but can still put 50 pounds plus

of baggage on board, when full.

The Piper

PA-28-180 is a surprising airplane in terms of what it offers

for its cost. If you can believe book figures, you can load all

four seats with 170 pound, FAA-size people, stuff all you can

get into its 50 gallon tanks and still carry 175 pounds of baggage

or cargo. Its sister airplanes, the Archer/Challenger give up

some weight-carrying ability but can still put 50 pounds plus

of baggage on board, when full.

The very early Cessna 170/172's can theoretically carry full fuel

with all four seats filled, but they aren't exactly barn burners

in climb. Later airplanes, like the Hawk XP and American General

AA-5 Tiger, along with various Mauls, do much better. However,

just because the spec sheets say the breed is supposed to have

such and such a useable load, take a look at the weight and balance

paperwork for any given airplane before believing the specs. Most

airplanes have gained a minimum of 50 pounds since leaving the

factory and that erases any baggage margin they may have had.

And then there are the Skylane and the Dakotas, which don't give

up anything to carry a load.

Cessna's 182 Skylane

First of all, the 182 is a different airplane than the Skylane:

the Skylane is a dressed up version of the basic bird. Except

for mostly cosmetic changes, there's little or no practical difference

so we're going to consider them interchangeable. What does make

a difference, however, is where a specific model falls in the

genealogy of the breed. All 182 Skylanes are not the same.

As originally introduced in 1956, the airplane had an empty weight

of 1540 pounds and a gross of 2,550 for a useful of 1010 pounds.

By the time equipment was added, the useful generally lost 50-75

pounds and you couldn't fill the 55 gallon tanks with four passengers.

That changed a year later when the gross went up 100 pounds and

the useful got an extra 80 pounds. Now you could fill everything

and still have 60 pounds of baggage. The good news was, however,

that even at gross, performance was, and is, still good. The early

airplanes have the same horsepower as the new ones and are 400-500

pounds lighters so climb better. The 182 A,B,C,D all fit this

profile.

The next big utility jump came in 1962. The airplane got it's

swept tail in 1960 with the "C" model but it became

the Skylane we all know and love (including electric flaps), when

it got its rear window in '62 as the 182E along with another 150

pounds increase to 2,800 pounds gross weight. This gave a useful

load of 1190 pounds and you could fill the bigger, 65 gallon,

tanks and still carry 100 pounds of baggage. The airplane had

become a very serious, 141 knot traveling machine as the range

was extended out to 550 nautical miles.

1970/71 were golden years for the guys who really wanted to move stuff because the airplane got yet another 150 pounds gross increase but the empty weight only went up 30 pounds for a 1310 pound useful load! The tanks were still 65 gallons so a pilot could load the seats and the tanks and carry a solid 220 pounds in cargo or extra load. In case you've lost track, that means two folks in a Skylane could fill the tanks and put nearly 600 pounds more in the airplane! With only two people on board and normal baggage, they really perform.

The "P" model came out in 1972 and a weird thing happened:

The empty weight went up 114 pounds but the gross stayed the same

so the useful went down to 1196 pounds. That's a backwards step

of 114 pounds. The folks at Cessna had something in mind, but

we don't know what because at the same time they increased the

tanks nearly 50% to a an unbelievable 92 gallons. If you put only

65 gallons in, you were still where the 1962 "E" model

was, but you were 66 pounds short of being able to fill the tanks

with four people on board.

Cessna definitely put things right with the 182QII. Notice the

II designation. There is both a PII and a QII and the significance

of the II has escaped us, although someone is bound to write in

with an explanation. One thing is certain however: when they bumped

the QII up another 150 pounds to 3,100 while holding the empty

weight increase to 25 pounds, they created a monster of an airplane.

The useful load became 1325 pounds, so they could top the 92 gallon

tanks, load the seats and still have room for 125 pounds of baggage.

That's impressive! The chronology of the P,Q,PII, QII is a little

vague as there were actually two series of fuel tanks, one with

"only" 84 gallons and, according to some sources, the

gross weight increase may not have applied to some of the early

airplanes. The airplanes produced from 1981 until the line shut

down in 1986, were all superhaulers unmatched by the second-generation,

1997 models which picked up over 100 pounds in empty weight because

of the new engine.

The Competition: Piper's Big Machines

Piper came into the aluminum airplane

era in a rather haphazard manner. A devout rag and tube airplane

company, the 1953 ex-Stinson Apache was their first venture into

sheet metal. The 180 Commache in 1958 was their first homegrown

effort.

Piper was still throwing together rag and tube as late as 1961,

the last year of Tri-pacer production and long after it was obvious

a change was in order. Piper then hired consulting engineer John

Thorpe who gave them the basic concept for an airplane they then

refined into the eventually long-winded PA-28 Cherokee series,

the first 140's hitting the streets in 1964.

One of the objectives of the new design was to have it be a "family"

of airplanes which appealed to different markets by virtue of

different engines on nearly identical airframes. The bottom of

the line 140 was the trainer, the 150/160 was designed to counter

the 172, while the lovely little 180 actually existed in a gap

between the competition's 172 and 182. It had no real competition.

It was in going after the 182 market that Piper designers took

the basic PA-28 to the limit. Hanging a 235 hp, six-cylinder 0-540

Lycoming on the nose, they produced an airplane that quickly carved

out a reputation as a heavy hauler.

The initial 1964 Cherokee 235 quickly mutated into the 235B of

1967 by the simple expediency of an interior redesign. With the

exception of 5" added to the fuselage and a 100 pound weight

increase to 3,000 pounds with the 1973 Charger, little changed

in the line from 1964 to 1977 when the line ended. The only changes

really worth noting are the sizes of fuel tanks.

The original airplanes through the "B" models had the

50 gallon tanks of the PA-28-180 with 84 gallons as optional.

The "C" of 1968 introduced those huge tanks as standard

but for some reason, when the Pathfinder (same airplane, different

gas tanks) was introduced in 1974, the tanks had shrunk to 62

gallons and they stayed that way until the line was replaced by

the Dakota. That's still a lot of gas, however!

The performance specs on the 235 Cherokee were remarkably stable

for the entire 13 years of its production. The useful load went

from 1465 pounds (that's not a typo, 1465 pounds and is more than

it's empty weight!) of the 235B down to 1408 pounds for the Pathfinder

in 1974. The big difference in the tank size, however, makes a

huge difference in the ultimate range. The "B"s and

earlier aircraft equipped with the smaller 50 gallon tanks had

pretty short legs, 408 nm being typical. Of course with those

tanks full, you could carry four people AND stuff a small-block

V-8 (469 pounds) in with them.

All of the later airplanes carried similar loads with the trade

off being more fuel for less load. When you tanked up a Charger

(84 gallons), for instance, its load over and above the passengers

dropped to 240 pounds (aw, gee!) while the Pathfinders (1974-1977)

carried 337 pounds because they only had 62 gallon tanks.

The fastest of the 235 Cherokees was the first series, the "B"s,

at 136 knots and they gradually slowed down until the Pathfinder

bottomed out at 126 knots. This trend was to be reversed with

the new Dakota.

The PA-28-236 Dakota was, like the Warrior, a warming over of

the basic airframe with special attention given to the wing. The

Dakota got the semi-tapered wing in place of the 235's aerodynamic

slab which, along with a lot of detail engineering and tweaking,

made a different airplane out of the old 235. Its useful load

dropped to 1392 pounds, but it could still carry 258 pounds of

baggage in addition to its passengers and 72 gallons of gas. Even

better, it could haul all this stuff around at a very respectable

143 knots. It was also a much better handling airplane than the

old 235 which could be heavy handed in some situations. However,

it should be noted that the fat Hershey bar wing of the 235 gave

the airplane a 200 fpm edge over the Dakota in climb.

How Do They Compare?

The obvious question is, "How does the 235/Dakota series

compare with the C-182 line?" The answer has to be "With

which 182?"

Where the 235 and Dakota were quite stable in terms of capabilities

through out their respective production runs, the C-182 was anything

but stable. Also, the changing size of the gas tanks in both airplanes

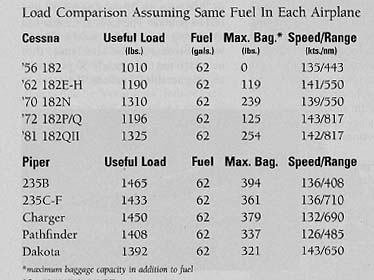

throws a variable in there that is difficult to correct for. So,

seeking a simple way to compare their load lifting capabilities,

we just assumed each of the airplanes was carrying 62 gallons

(the smallest tank common to the Cherokee line) and calculated

how much load it could carry in addition to four full sized passengers.

Both airplane types are obviously capable of carrying alot of goodies but in pure weight lifting, the nod has to go to the Cherokee. In both cases, however, some consideration has to be given to not only cabin size and access but how much can be carried in the baggage compartment versus what portion of the load has to be in the main cabin. Also, if you're loading a heavy object into the cabin, the high wing of the 182 would make loading it much easier than climbing up on the wing of the Cherokee.

Notice the speed trends between the two airplanes. The 182 steadily

increased, although at 135 knots, even at the beginning it was

never particularly slow. Also, during its production span it increased

over 500 pounds in gross weight which should have slowed it down,

an indication the aerodynamicists at Cessna earned their salaries.

The 235 on the other hand only increased 100 pounds in gross weight

yet its cruise speed steadily decreased until the complete redesign

that became the Dakota brought it up on a par with the latest

182.

Now let's look at real load carrying with full tanks as well as

current values. The prices quoted are base Blue Book values and

only offer a relative comparison as they are generally lower than

those found in the marketplace.

The prices reflect not only both airplanes' popularity but, in the case of the Dakota, they also reflect the age, as the airplane was produced much later than the 182, 1979-1994.

The Wild Card Dakota 201T

In the first year of Dakota production, the airplane was also produced with a turbocharged TSIO-360 Lycoming of 200 horsepower in addition to the 0-540. The airplane gave impressive book cruise figures of 154 knots and had a useful load of 1320 pounds, but the airplane was produced for only one year.

To Summarize

There are people who swear by both the Cessna182 and the 235/236

Piper. Sometimes their allegiance is a matter of Lycoming (Piper)

versus Continental (Cessna), most of which is rooted in the Continentals'

annoying habit of cracking cylinders. Many may argue the fact,

but big Continentals simply require more judicious handling than

do Lycomings.

The high wing, low wing thing probably plays a role in type preferences

as do a dozen other factors. All Cherokees fly like much heavier

airplanes giving them a "big airplane" feel that sometimes

works to their advantage in turbulence and crosswinds. They however

stall a solid two to five miles an hour faster than do Cessna's

and their flaps aren't known for their effectiveness. The upkeep

on the Cessna's taper rod or spring steel gear is next to zero

while the three oleos on the Cherokee do require some attention.

The final decision is a simple one: Get a flight in each at full

gross weight and see how you like them. Really work them, including

some short field and crosswind work. Then take the one that feels

the best, both physically and financially. That way you'll sleep

better at night.